Sixty years ago this month, the August 1960 issue of Popular Electronics was a particularly good one. In an upcoming post, we’ll feature one of its construction articles, the elusive loudspeaker crystal set. There’s also a primer on soldering, and a guide to restoring shortwave receivers from the 30s and 40s and turning them into state-of-the-art communications receivers. There’s even the obligatory one-tube radio, namely a one-tube superregenerative receiver for the FM broadcast band.

Sixty years ago this month, the August 1960 issue of Popular Electronics was a particularly good one. In an upcoming post, we’ll feature one of its construction articles, the elusive loudspeaker crystal set. There’s also a primer on soldering, and a guide to restoring shortwave receivers from the 30s and 40s and turning them into state-of-the-art communications receivers. There’s even the obligatory one-tube radio, namely a one-tube superregenerative receiver for the FM broadcast band.

The issue also showed the ambitious cover project, a portable oscilloscope. These days, of course, you can get a much better one at a much lower price, such as the one shown at left, conveniently available on Amazon.

The issue also showed the ambitious cover project, a portable oscilloscope. These days, of course, you can get a much better one at a much lower price, such as the one shown at left, conveniently available on Amazon.

And one particularly intriguing teaser on the cover promises to tell you all about unlicensed two way radio. The magazine was pointing to FCC rules that are still in effect today in more or less the same form, namely Part 15. Among other things, they allow license-free broadcasting on the AM broadcast band, as long as the transmitter input power is less than 100 milliwatts and the antenna is less than 10 feet long (today, strictly speaking, the allowable antenna is now two inches shorter, because the limit is now 3 meters). Of course, you also need to avoid interference with licensed stations. The magazine explained how you could use two transmitters, along with two broadcast receivers, for a two-way operation. It gave other ideas on how to use such a transmitter, such as mounting it in a car, to stay in touch with another car that’s driving with you, or even to talk to the house while driving by.

Back in the day, as the source of your transmitter, the magazine recommended a wireless phono oscillator. We’ve discussed these before, and they were readily available, either assembled or in kit form, to listen to a phonograph on a nearby radio. These units usually had a range of 50-100 feet. But with the full-size (10 foot) antenna carefully placed, the range could be much greater. According to the magazine, the signal could be picked up by a good car radio a half mile away.

Due to COVID-19, home broadcasting is making a comeback. In particular, there are many applications where you might want to broadcast to nearby car radios. A church, for example, can have its service in the parking lot, with churchgoers listening on the car radio. They can see the altar, but they’re safely distanced in their car. Along with an inexpensive video projector, neighbors can come together for an impromptu drive-in movie.

Review of the Talking House AM Transmitter

Of course, there’s no such thing as a phono oscillator any more, so where do you get a good transmitter? The answer is the transmitter shown at the left, the reasonably priced InfOspot Talking House transmitter. I recently bought one, and I am absolutely amazed at how well it works.

Of course, there’s no such thing as a phono oscillator any more, so where do you get a good transmitter? The answer is the transmitter shown at the left, the reasonably priced InfOspot Talking House transmitter. I recently bought one, and I am absolutely amazed at how well it works.

The name derives from the fact that it was originally marketed to real estate agents. The agent would record a short sales pitch for the house, put a sign outside inviting passers by to tune in to a particular spot on the dial, and the house would literally start selling itself.

Because this is the intended use, the Talking House has a built-in digital recorder. You can record a continuous loop of up to about five minutes. Earlier models of the Talking House were capable of only the continuous loop–you couldn’t broadcast live with them. Before I bought the model shown above, I bought one of the older models on eBay. It had an excellent transmitter, but wouldn’t work for live programming without some modification. I was tempted to break out the soldering iron and tap into the audio line, but with the low price of the newer model, I decided to just get it. The transmitter has two inputs in the back, one for a microphone, and the other for a line-level input, such as from a PA system. These inputs can be used to record a loop on the built-in digital recorder, or for live audio. I tested the unit by recording a program on my MP3 player consisting of music and voice. I set it up in my ground floor home office, stretched out the 3 meter antenna, plugged it in, and went on the air.

You can select any frequency from 530-1700 kHz. When you plug the transmitter, you can hear a small electric motor running the built-in antenna tuner. The assures the best possible antenna match, and the best possible signal. After starting it up, I walked around the house with a portable radio admiring the audio quality. Then, of course, I hopped in the car to see how far I was getting out.

Given the short antenna inside the house, I was absolutely blown away at how well it got out. It easily covered the city block. There were a couple of spots where the signal dropped out slightly, but it was broadcast quality within the block. I kept driving and driving. The signal got weaker, but it was still very listenable several blocks away in most directions. There were spots where it dropped out, but I had almost 100% coverage (with a good car radio) out about a half mile. When I explored further out, I found many “sweet spots” where I had an excellent signal more than a mile away. My best DX was over 2 miles, since there were a few places where I could positively identify my signal at that distance.

I’m astonished at how well this transmitter works. And it is FCC certified as complying with part 15, so there is no question as to its legality. You only have to ensure that you’re using a vacant spot on the dial so as not to interfere with licensed stations. In my case, I use 1610 kHz. In the U.S., that frequency is used only for Traveler Information Service (TIS) stations, and there are none close by.

One might be tempted to purchase an FM transmitter, rather than one for the AM band. There’s a knee-jerk reaction by some that the audio quality is better on FM. That’s not necessarily true, since it depends on the quality of the transmitter. An AM signal can have an excellent frequency response, and the Talking House has excellent audio, probably better than a cheap FM transmitter.

The main problem with buying an FM transmitter is that it’s probably not legal. The requirements for license-free FM transmitters are such that the signal must be extremely weak to be legal. A good receiver 100 feet away probably wouldn’t be able to pick it up. If a transmitter performs better than that, then it’s probably not legal. If you use it for a few minutes per week, you probably won’t get caught. But fines are typically in the range of $10,000 per day, and in my opinion, it’s just not worth the risk, particularly since the Talking House AM transmitter works so well.

There are many uses for this transmitter, and it seems like a very useful item to keep on hand. In addition to drive-in church services and impromptu drive-in movies, it could be very useful to broadcast information in the neighborhood in case of emergency. It comes with a “wall wart” power supply for the 18 volts needed to power the unit. It could be run on batteries, but since the wall wart’s ground lead is an integral part of the unit’s antenna system, it seems best to run it on a small inverter power supply in an emergency, even the smallest of which would be adequate.

One accessory that is necessary if using an external audio source is an audio isolation transformer, to prevent ground loops. When I plug in my MP3 player, it sounds great. But if hook up to an AC adapter, the hum overwhelms the signal. The isolation transformer prevents this. It’s necessary if feeding the audio from any device, such as a computer, that is plugged in to the AC power.

If, for whatever reason, you want to legally broadcast, and have people be able to listen to you up to a mile away, sixty years ago, I would have told you to go to Lafayette or Allied and get a good phono oscillator. And today, it’s even easier. All you need is a Talking House transmitter, and you’ll be on the air the same day your Amazon order arrives.

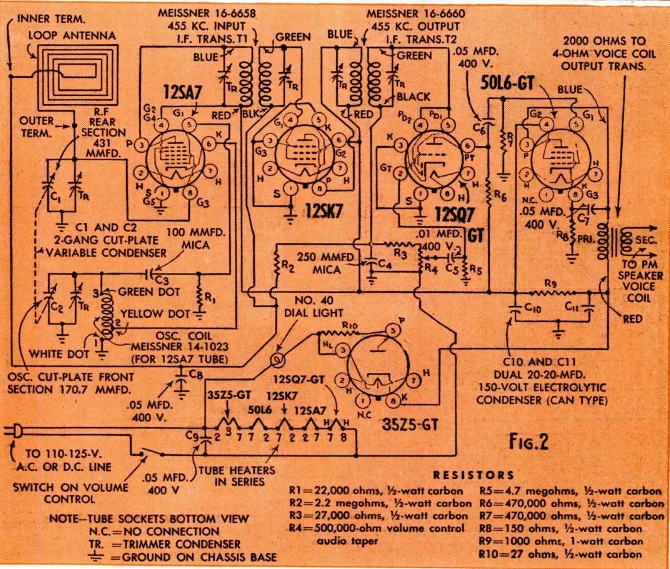

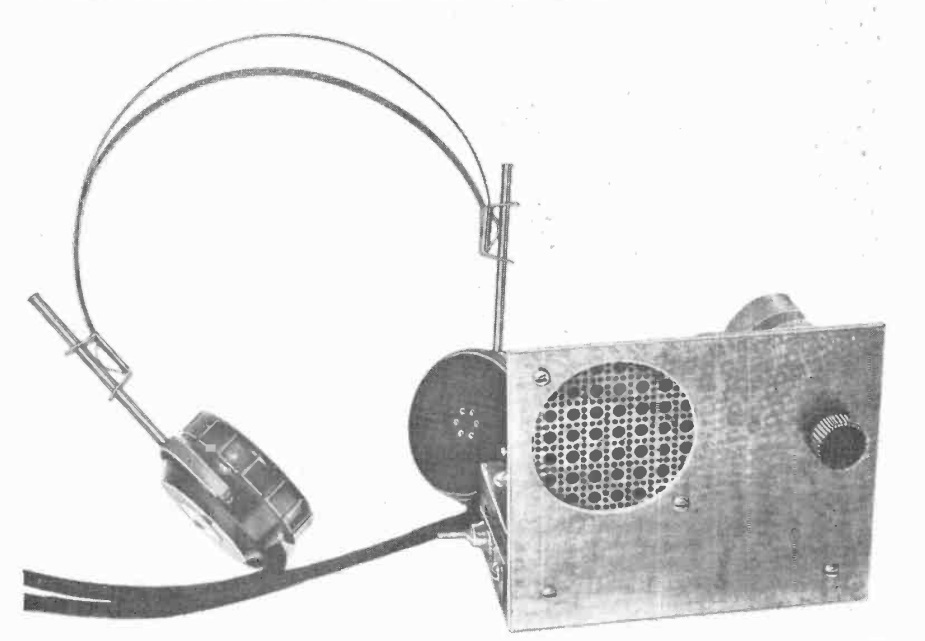

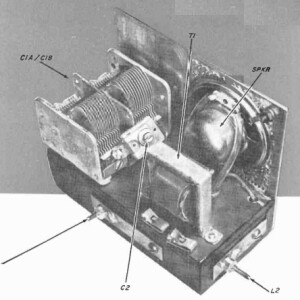

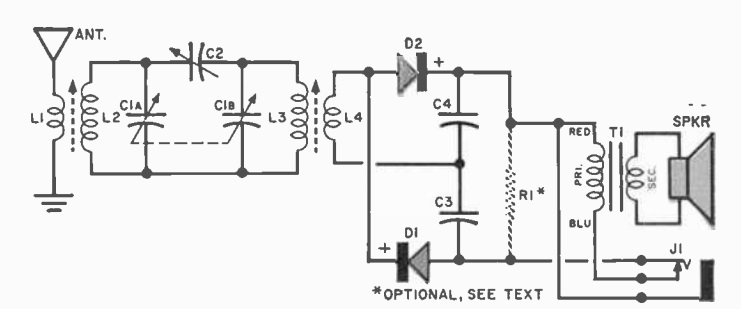

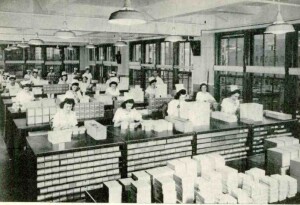

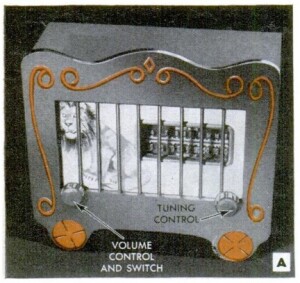

These lucky youngsters have probably been drawing Social Security for about a decade, but in 1950, they were tuning in a favorite program on this attractive five-tube radio put together by their dad and big brother. The internal circuitry was a typical “All American Five” superhet, with a tube lineup of 12SA7, 12SK7, 12SQ7, 50L6, and 35Z5 rectifier. Since this was an AC-DC set, the article cautioned that the screws holding the chassis to the wooden case should be covered up for safety.

These lucky youngsters have probably been drawing Social Security for about a decade, but in 1950, they were tuning in a favorite program on this attractive five-tube radio put together by their dad and big brother. The internal circuitry was a typical “All American Five” superhet, with a tube lineup of 12SA7, 12SK7, 12SQ7, 50L6, and 35Z5 rectifier. Since this was an AC-DC set, the article cautioned that the screws holding the chassis to the wooden case should be covered up for safety.