Minutes after totality.

The total solar eclipse was awesome, and well worth the trip to Hastings, Nebraska!

Travel Report

We left Minnesota on Saturday and drove to Fremont, Nebraska. The traffic was noticeably heavy on both Interstate 35 and Interstate 80. Many of the vehicles we saw were obviously eclipse chasers, with cars packed full of camping gear. The heavy traffic was very apparent when we turned off onto I-680 to get to our hotel room in Fremont. That highway was deserted, which appeared all the more eerie after witnessing the extremely heavy traffic directly on the route to the path of totality. On Sunday, traffic was heavier still as we moved back onto the interstate, but was still moving at posted speeds.

We were in position by Monday, so we didn’t experience traffic the day of the eclipse. It was reported to be heavy, but with no major delays. The only eclipse-related traffic issue was an announcement on the radio that the Nebraska Highway Patrol had closed both I-80 rest areas near Grand Island for safety reasons. Gasoline and other supplies were readily available at normal prices.

According to reports, traffic was heaviest after the eclipse as hundreds of thousands of visitors headed home. Still, no major issues were reported, and traffic, while somewhat slower than normal, was moving along well. We drove home Tuesday. While traffic appeared normal by the time we were on the road, many cars were obviously those of other eclipse chasers, as evidenced by the camping gear filling many of them.

Viewing the Eclipse

On Monday morning, we set up in American Legion Park in Hastings, a small city park just across the street from our hotel. Other viewing areas were packed, but we shared the park with only about a dozen other visitors, mostly from Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Iowa. There were street lights on the neighboring road, but we stayed clear of them and they didn’t present any obstacle to our viewing.

We didn’t bother trying to take photos of the eclipse. We only had two minutes, so rather than fiddling with cameras during that time, we simply enjoyed the spectacle and left the photography to professionals.

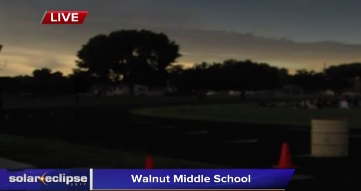

The best representation I’ve seen so far of what we experienced is from NBC Nebraska at this link. if you click on Part 3 of the video at that link, and then advance to the 4:00 minute mark, you’ll see a live report from a Middle School in Grand Island, about 20 miles north of where we were. The video does a good job of capturing the darkness of the sky, as well as the reaction of those present. The video doesn’t do justice to the corona itself, but all of the other elements reflect very well what we witnessed.

It’s also evident from the video what I kept saying before the eclipse: The eclipse was something that kids needed to see! The reaction of the middle school kids in this video was overwhelming, and the eclipse is something that they will never forget. It’s a shame that some schools locked their kids inside rather than taking them to see it. There are now undoubtedly many future astronomers and scientists among the kids in Grand Island and other places where enlightened educators made it a unique learning experience. The kids who were left inside for the eclipse did not get that inspiration, and any school administrators who took that approach should be ashamed of themselves.

In Hastings, there were thin scattered clouds throughout the morning. However, with the cooling caused by the eclipse, the sky was clear during totality, the clouds not reappearing until about 10 minutes later. It was noticeably cooler starting a few minutes before totality. Even though the surroundings were not noticeably dimmer to the human eye until just before totality, the direct sunlight didn’t feel warm as it had in the morning.

We saw the diamond ring both before and after totality. I did not see Bailey’s Beads, nor did I see any shadow bands. The horizon in all directions had the orange glow of sunset. Venus was plainly visible. I didn’t notice it before totality, but it persisted for a couple of minutes after the sun returned.

Radio Experiments

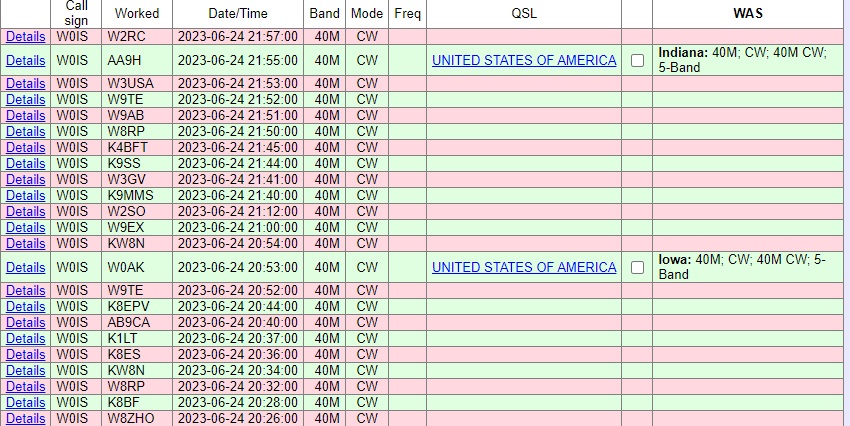

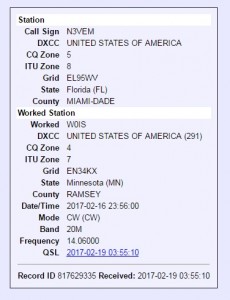

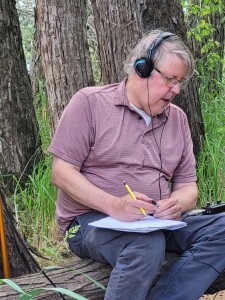

As shown here, I was doing my part for science by operating in the HamSci Solar Eclipse QSO Party. Along with other amateur radio operators, I was operating in this event to generate data which researchers will use to understand the ionosphere and how it was affected by the eclipse. Radio signals are reflected by the ionosphere, and the effect varies depending on frequency, and depending on the amount of solar energy hitting the ionosphere. The eclipse gave a rare opportunity to show the effects when the amount of solar energy varies over small areas, such as the path of totality. I concentrated mainly on making short transmissions to be picked up by remote receivers. Some of these receivers are connected in real time to the Reverse Beacon Network, which displays received signals almost immediately on the Internet. Unfortunately, my signals were not picked up by these stations, but other software-defined receivers were continuously recording the radio spectrum, and it’s likely that my transmissions were recorded and will be available at a later date.

As shown here, I was doing my part for science by operating in the HamSci Solar Eclipse QSO Party. Along with other amateur radio operators, I was operating in this event to generate data which researchers will use to understand the ionosphere and how it was affected by the eclipse. Radio signals are reflected by the ionosphere, and the effect varies depending on frequency, and depending on the amount of solar energy hitting the ionosphere. The eclipse gave a rare opportunity to show the effects when the amount of solar energy varies over small areas, such as the path of totality. I concentrated mainly on making short transmissions to be picked up by remote receivers. Some of these receivers are connected in real time to the Reverse Beacon Network, which displays received signals almost immediately on the Internet. Unfortunately, my signals were not picked up by these stations, but other software-defined receivers were continuously recording the radio spectrum, and it’s likely that my transmissions were recorded and will be available at a later date.

I didn’t spend much time trying to make two-way radio contacts, but I did make three contacts, which are shown on this map:

All three of these contacts were made before totality. I was operating on the 40 meter band (7 MHz) with only 5 watts of power, and the distances of these contacts does seem much greater than would normally be expected that time of day. The most distant contact was with WA1FCN in Cordova, Alabama, 776 miles from my location in Hastings, Nebraska. We made this contact at 12:29 PM local time, about 30 minutes before totality. It seems likely that this contact was possible only because of the eclipse. The contact with N5AW in Burnet, Texas, 680 miles away, was made at 12:10 local time, and the contact with W0ECC in St. Charles, Missouri, 438 miles away, was made at 11:08 local time. In all three cases, the partial eclipse was underway at both locations when we made our contacts.

The HamSci researchers at Virginia Tech will have a lot of data to analyze, but I think it’s clear that the eclipse was having an effect on propagation. The 40 meter band is generally limited to shorter distances during the day, and the path lengths here seem more consistent with the type of propagation normally seen in the evening.

For those who are interested in the details, my station consisted of my 5 watt Yaesu FT-817 powered by a 12 volt fish finder battery. The antenna was a 40 meter inverted vee with its peak about 15 feet off the ground, supported by my golf ball retriever. The two ends of the antenna were supported by tent stakes in the ground. The station was similar to what I used in 2016 for many of my National Parks On The Air activations. The antenna was running north-south in an effort to have its maximum signal along the east-west path of totality. Since the antenna had an acceptable match on 15 and 6 meters, I also made a few test transmissions on those bands, although I concentrated on 40 meters.

Nebraska and the Eclipse

The State of Nebraska, the City of Hastings, and all of the other towns we encountered along the way, did an excellent job of planning for the eclipse and accommodating all of the visitors. While traffic was very heavy, there were no real problems. The staff of our hotel, the C3 Hotel & Convention Center, was extremely well prepared for what was probably the hotel’s busiest night ever. The accommodations were excellent!

Since virtually all of the hotel rooms in the state were filled, dozens of temporary campgrounds sprung up, and visitors were able to find safe campsites at a reasonable price as homeowners, farmers, and ranchers opened their land for camping.

The only traffic-related problem that I’m aware of was the closure of two highway rest areas shortly before totality. Unrelated to the eclipse, the City of Seward, Nebraska, experienced an ill-timed water main leak, leaving the city without drinking water during the eclipse. We did see units of the Nebraska National Guard on the road, but as far as I know, other than to distribute drinking water in Seward, their services were not needed during the eclipse.

The entire state deserves high marks for its preparations in making the eclipse an unforgettable event for the hundreds of thousands of visitors.

Get your Eclipse Glasses for 2024 at: MyEclipseGlasses.com

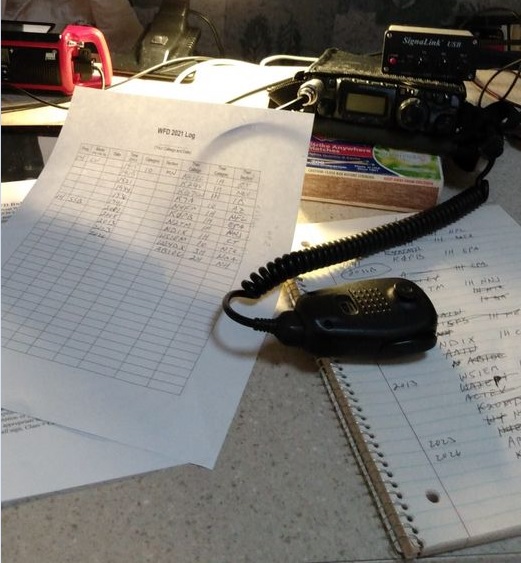

This past weekend was ARRL Field Day, an operating event in which Amateur Radio operators set up in the field and see how many contacts they can make with portable equipment. It’s mostly a fun activity, but it also serves as a test of emergency capabilities. For many, this involves hauling large equipment, often powered by a gasoline generator, and setting up large antennas. Often, large groups are involved in these operations. It’s been around since 1933, so this year’s running marked the 90th anniversary.

This past weekend was ARRL Field Day, an operating event in which Amateur Radio operators set up in the field and see how many contacts they can make with portable equipment. It’s mostly a fun activity, but it also serves as a test of emergency capabilities. For many, this involves hauling large equipment, often powered by a gasoline generator, and setting up large antennas. Often, large groups are involved in these operations. It’s been around since 1933, so this year’s running marked the 90th anniversary. I prefer a simpler approach, and set out by myself or a smaller group with equipment that I can easily carry and quickly set up. This year, instead of just driving to a park, I decided to operate from an island accessible only by boat. In particular, I operated from Greenberg Island in the St. Croix River, part of William O’Brien State Park, Minnesota. The plan was for my wife and I to do the operation, bringing our canoe from home.

I prefer a simpler approach, and set out by myself or a smaller group with equipment that I can easily carry and quickly set up. This year, instead of just driving to a park, I decided to operate from an island accessible only by boat. In particular, I operated from Greenberg Island in the St. Croix River, part of William O’Brien State Park, Minnesota. The plan was for my wife and I to do the operation, bringing our canoe from home.