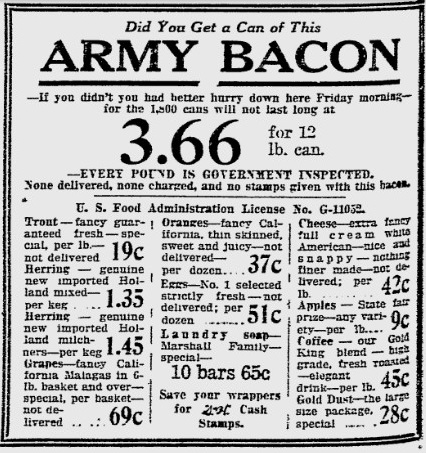

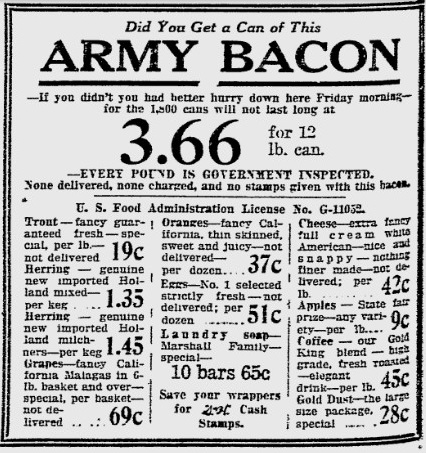

With World War 1 soldiers on their way home or already there, the U.S. Army had some surplus commodities to get rid of a hundred years ago, and that included bacon. This ad appeared in the Milwaukee Journal a hundred years ago today, September 25, 1919, for the Boston Store in Milwaukee.

With World War 1 soldiers on their way home or already there, the U.S. Army had some surplus commodities to get rid of a hundred years ago, and that included bacon. This ad appeared in the Milwaukee Journal a hundred years ago today, September 25, 1919, for the Boston Store in Milwaukee.

The store offered mostly dry goods, ranging from from toilet paper (6 rolls for 19 cents) up to a player piano ($395). They also had a limited selection of food items, apparent “loss leaders” to get traffic into the store, shown at left. And, of course, what stands out is the twelve pound can of army bacon for $3.66. That, of course, is before a century of inflation, but a good way to put old prices in context is to remember that the money was made out of silver, so that the $3.66 really meant about 3.66 ounces of silver. Today, that would be about $60.

That’s still a reasonable price, however. The current WalMart price for 12 pounds of bacon is about $53. That bacon, of course, isn’t really suitable for long-term storage, whereas the 1919 product was canned. Interestingly enough, though, canned bacon is still readily available, and can be purchased at Amazon. As you can see below, it’s rather expensive, especially considering that this price is for a nine ounce can:

That’s still a reasonable price, however. The current WalMart price for 12 pounds of bacon is about $53. That bacon, of course, isn’t really suitable for long-term storage, whereas the 1919 product was canned. Interestingly enough, though, canned bacon is still readily available, and can be purchased at Amazon. As you can see below, it’s rather expensive, especially considering that this price is for a nine ounce can:

On the other hand, for your emergency food storage needs, it might fill a niche. According to the reviews, the product is excellent, and the 9 ounce can contains about 50 slices of bacon. So having a can or two in the pantry might not be out of the question.

Since the modern product has 50 slices in the 9 ounce can, this means that the 12 pound can from 1919 contained several hundred slices. So it probably was worth racing down to the store to get a couple cans.

If you’re looking for more ideas for protein for your home food storage, the most economical is probably dry beans or perhaps peanut butter. If you crave real meat, one of the cheapest is probably tuna. Other good options are potted meat, canned chicken, or, of course, the venerable Spam. But if you want to get a can or two of canned bacon, I can’t blame you.

For more information about emergency food storage, see my food storage page.

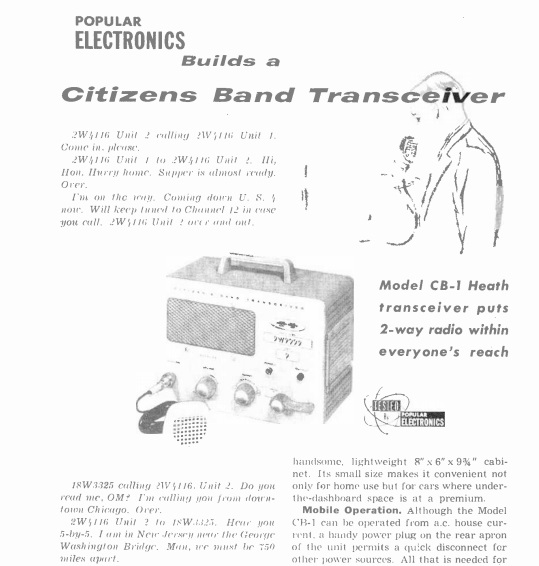

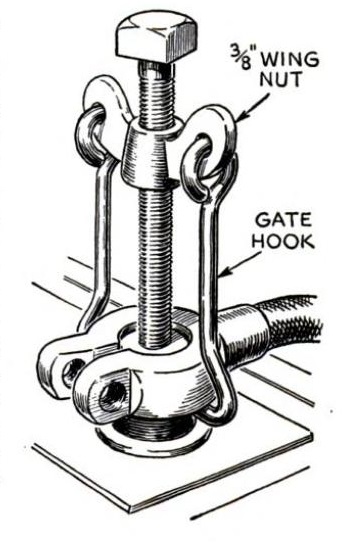

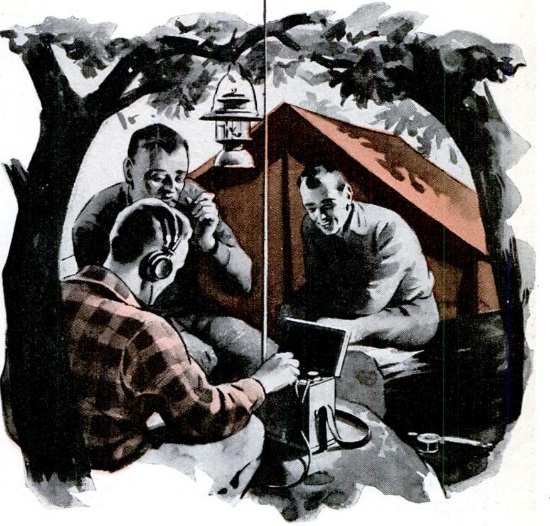

This trio are pulling in stations from their campsite thanks to the three-tube portable described in the September 1939 issue of Popular Science. Just like the patio set described in the previous month’s issue, the set used three miniature tubes imported from England, although with the war just underway, it might have been hard to get more after the U.S. stocks were depleted. Apparently, the men had come to terms about taking turns with the headphones.

This trio are pulling in stations from their campsite thanks to the three-tube portable described in the September 1939 issue of Popular Science. Just like the patio set described in the previous month’s issue, the set used three miniature tubes imported from England, although with the war just underway, it might have been hard to get more after the U.S. stocks were depleted. Apparently, the men had come to terms about taking turns with the headphones.