By 1944, with able-bodied men off to war, a third of the Civil Service was composed of women, and thousands of “Government Girls” descended on Washington to do their part to win the war by taking jobs in the quickly expanding federal government.

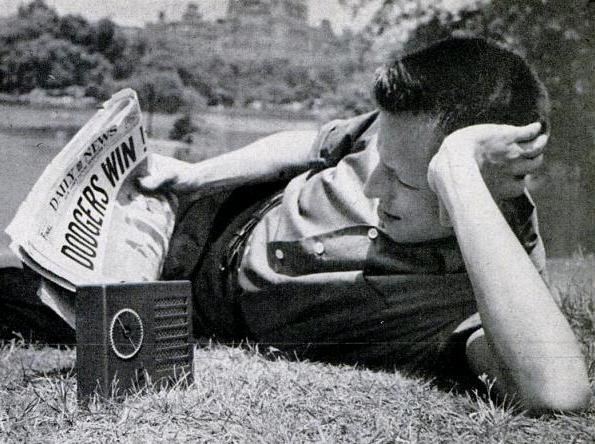

This brought acute housing shortages, and many of them lived in boarding houses. Among them was the young woman shown here in this iconic photograph by government photographer Esther Bubley. Bubley was herself one of those Government Girls. She grew up in Superior Wisconsin. After graduating from high school in the late 1930’s, she attended Superior Teachers College (now University of Wisconsin-Superior) before studying photography at the Minneapolis School of Art (now the Minneapolis College of Art and Design).

“I come in here pretty often, sometimes alone, mostly with another girl, we drink beer, and talk, and of course we keep our eyes open–you’d be surprised at how often nice, lonesome soldiers ask Sue, the waitress, to introduce them to us” Wikimedia.

She moved to Washington in 1942, eventually landing a job as a photographer with the Office of War Information, where she documented the home front, including the lives of her fellow civil servants, such as the one shown above, taken in January 1943, with the caption: “A radio is company for this girl in her boardinghouse room.” Another civil servant is shown in the picture to the left.

The girl in the radio picture is, according to this source, quite likely one of Bubley’s sisters. The boardinghouse project was Bubley’s first in Washington. Even though she started out as a microfilm clerk, the results launched her career as a photographer.

The other star of the photo is, of course, the radio. It can be examined in better detail in the available high resolution scan. There aren’t enough details to positively identify it. I thought that the unusual octagonal tuning dial would make the job easy, but I was wrong.

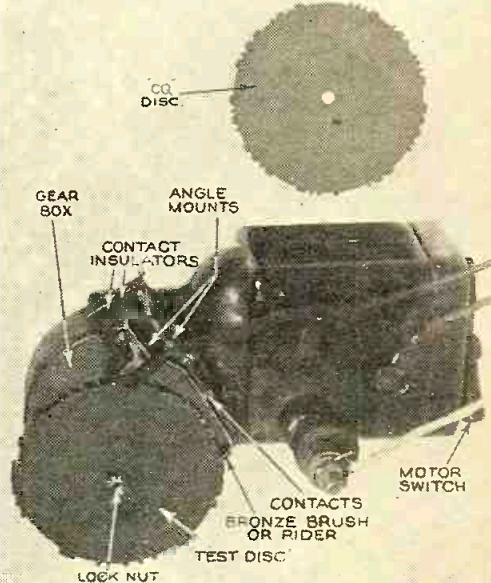

Stromberg-Carlson did have a number of sets with the distinctive octagonal tuning dial, but this doesn’t appear to be a Stromberg-Carlson. First of all, the set is just too low-end for that company’s line. It has only two controls, and the tuning knob is connected directly to the tuning condenser, with no kind of gearing visible. More importantly, the Stromberg-Carlson name is not visible. It would almost certainly have appeared on the dial itself, but the only markings on this one are “kilocycles” and “meters.”

There is a brand name visible under the speaker, but it’s not possible to make it out. It appears to start with either an M or a W, but it certainly isn’t the same script used by Stromberg-Carlson. Despite the passing resemblance to some of Stromberg-Carlson’s sets, I have to rule it out. If anything, it’s a cheap knockoff of a Stromberg-Carlson.

It’s most likely that the radio had its beginnings in the nebulous radio history of Chicago. There’s a good chance that it was manufactured in a mysterious facility known only as “Plant A,” 1217 W. Washington Blvd. Chicago was the home of many small radio factories, the largest of which was “Plant A.” They were known only by the source given on the label in back, which also recited that they were manufactured under license of the patent holders. And good number of them identified the source as being “Plant A.” Plant A turned out radios under the names of Clinton, Corona, Crusader, Cub, Bostonian, Buckingham, Federal, Harmony, Marshall, Nightengale, Universal, and Westminster. In most cases, these were the house brands of individual stores who contracted with the owners of Plant A.

It’s really not known who the owners of Plant A and the other Chicago plants were. One source lists the owner as being Clinton Mfg. Co., but it’s not entirely clear whether Clinton owned the plant, or whether it was simply one of the brands manufactured there.

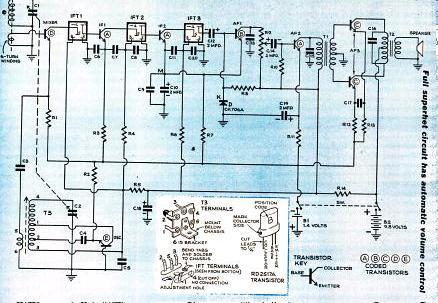

In any event, the circumstantial evidence seems strong that the radio came from one of these Chicago plants. Civilian radio production ended on April 22, 1942, and the set resembles the inexpensive four-tube radios that were available in about 1940. For example, the circuit is probably very close to the Tiny Knight from Chicago’s Allied Radio, or the 1940 Aetna Midget from Chicago-based Walgreen’s. Like those sets, the Government Girl probably paid about $7.95 for it at a drug store, tire store, or some other store that contracted with a factory in Chicago to put their name on it.

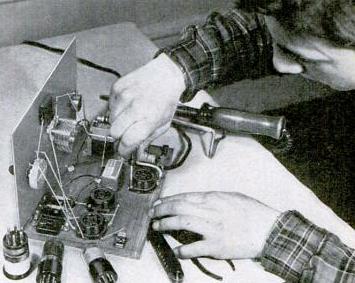

The closest match I was able to find to the Government Girl’s radio is this Clinton Model 440 4-tube TRF receiver. The general layout is the same, and it’s quite possible that there’s an identical chassis inside. In fact, the Clinton seems to have a permanently attached antenna wire, which is visible in the Government Girl’s window.

Now that we have a good suspicion of what the radio was, I’m sure you’re wondering what station the Government Girl was listening to. The dial pointer is visible in the high resolution photo, but it’s impossible to read the numbers. But the top scale is clearly frequency in kilocycles, and the bottom scale is wavelength in meters. The numbers are closer together at the left on the meter scale, indicating that this is the top of the dial (190 meters, or 1600 kilocycles). With that hint, it’s clear that the dial is set to 250 meters, meaning that the position of the top scale is 1200 kilocycles.

The Winter 1943 issue of White’s Radio Log shows that the most likely station as WOL, on 1260 with 1000 watts. The closest possible other contenders would have been 50,000 watt stations WBAL in Baltimore, on 1090, or WRVA on 1140 in Richmond, but it doesn’t appear that the dial is set low enough for either of those stations. In fact, with the simple 4-tube receiver and dubious window antenna, the signal from the Richmond station would probably have been too weak to keep the set’s owner company.

Incidentally, even though the caption says that the radio was keeping her company, it was turned off when the picture was taken. Even a humble radio such as this one would have had a dial light. The dial light wasn’t there as a convenience for the user; that was just a convenient side-effect. In a radio such as this with the tube filaments wired in series, the dial lamp is in parallel with some of the tubes to limit the current to them. Without the dial light, those tubes would fail prematurely, especially when the set is first turned on. So even the radio that a Government Girl bought at the drug store for $7.95 would have had one.

I would like to thank the QRZ.com members who helped me figure out the mysteries of this radio, in particular KP4SX and KC8VWM. And if anyone has further details, please share them, either by e-mail or in the comments.

Read More at Amazon

Click Here For Today’s Ripley’s Believe It Or Not Cartoon

![]()