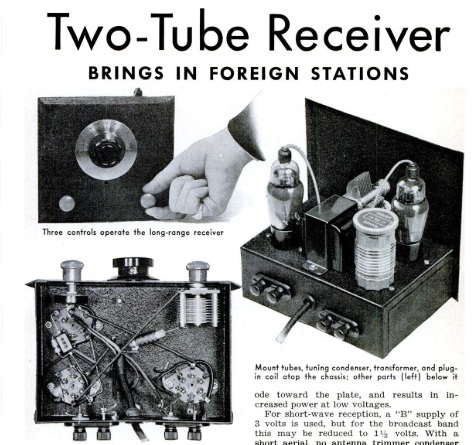

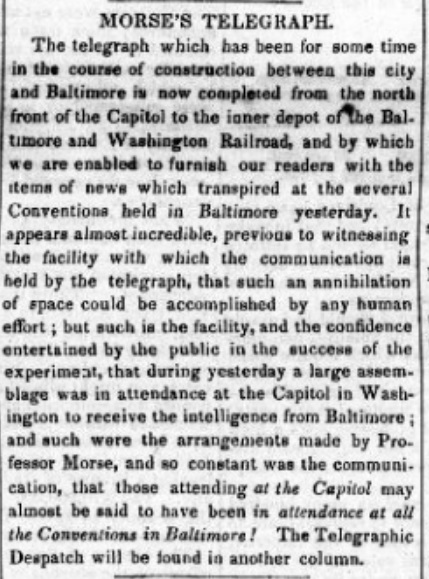

Meals packed by our group in 2016, on their way to Haiti, Nicaragua, or the Phillipines.

Join us in volunteering to fight world hunger! Friday, June 7, 6:00 PM, Minnesota State Fairgrounds.

We previously posted about Feed My Starving Children (FMSC), a Christian relief organization which packages meals for distribution to malnourished children around the world. The meals are packaged by volunteers and then distributed by partner organizations around the world.

There is currently a large demand for meals, and on June 7-8, the organization is looking for 5000 volunteers to pack one million meals. You’ll be part of a small assembly line that assembles the ingredients, seals them in a plastic bag, and then packs them into cartons and pallets for shipment. You’ll probably be told which country will be receiving the meals you pack. You can read more about the event at this link. It’s a fun work environment. You’ll be working almost the full time, but the work is not strenuous. Children 5 and older are welcome with accompanying adult.

OneTubeRadio.com Night at FMSC!

On Friday and Saturday, June 7-8, FMSC will be running seven shifts. Each one is about 2-1/2 hours long. My family will be attending, and I signed up our group under the name OneTubeRadio.com. We will be working on Friday, June 7, at 6:00 – 8:30 PM at the Minnesota State Fairgrounds, 1265 Snelling Ave. N., St. Paul, 55108. Plenty of free parking is available. Also, free passes on Metro Transit are available.

We would love to have others join us! If you want to join us, you have three options. If you wish, you can contact me at clem.law@usa.net and I’ll add you to our reservation. You can also add yourself to the group with this link. If you sign up yourself, please let me know you’re coming, although if you’re an introvert and prefer to attend under the cloak of anonymity, that’s perfectly OK.

Our group will meet at about 5:30 near the Butterfly House, at the corner of Dan Patch and Underwood. (I’ll give you my cell phone number, and we’ll also have talk-in on 146.52 MHz.) The packing event itself starts at 6:00 in the Grandstand building. If you’re running late, you can simply meet us there.

If you can’t make it Friday evening but want to sign up for another shift, you can do so at this link. Many other businesses and organizations are also promoting the event. For example, see the links from KTIS radio and HandsOn Twin Cities.

Some of the shifts will fill, so please sign up or contact me as soon as possible to reserve your spot. You will make a real difference in ending hunger in the world. And, if you wish, you can have your picture appear on a world-famous blog (namely, this one). If you are not able to attend, please consider making a monetary donation.

FMSC is a Christian organization, and the evening concludes with a prayer over the packaged meals. However, they are truly welcoming to those of all faiths or of no faith.