I don’t remember if I saw this particular magazine, the November 1970 issue of Popular Mechanics, but I did see magazines like it, and I was intrigued. I had absolutely no interest in sports, but I was interested in pulling in distant TV stations. We had it pretty good for television signals in Minneapolis-St. Paul. We had 5 VHF stations, and if you moved the loop antenna just right, you could pull in channel 17 on the elusive UHF dial. Our local newspaper and the local edition of TV Guide listed only these channels. In the paper, channels 2-11 were shown in a grid, with the schedule for channel 17 printed in small type in a corner of the page.

I don’t remember if I saw this particular magazine, the November 1970 issue of Popular Mechanics, but I did see magazines like it, and I was intrigued. I had absolutely no interest in sports, but I was interested in pulling in distant TV stations. We had it pretty good for television signals in Minneapolis-St. Paul. We had 5 VHF stations, and if you moved the loop antenna just right, you could pull in channel 17 on the elusive UHF dial. Our local newspaper and the local edition of TV Guide listed only these channels. In the paper, channels 2-11 were shown in a grid, with the schedule for channel 17 printed in small type in a corner of the page.

But occasionally, we would travel to surrounding areas, and when we did, if I could scrape together enough change, I bought a copy of TV Guide. The Minnesota edition listed all of the Twin Cities stations, but it was also chock full of listings of other stations. By and large, they were all the same programs. But some of my favorites were on at different times. I just needed a way to pull in these stations.

We never did it, because the rabbit ears worked just fine for our local channels. But I dreamed of putting up an outdoor antenna to pull in those elusive signals. Articles like this spurred my dreams.

This particular article was penned by prolific electronics writer Len Buckwalter. The target audience was sports fans. Games were “blacked out” in those days. Football was particularly affected by these “blackouts”. Today, sports is a television event. But then, the thinking was that if the game were on TV, attendance at the stadium would suffer. They figured that nobody over a hundred miles away would drive to see the game, so it was safe to put it on TV there. But unless the game was sold out, it wouldn’t be televised locally.

So if you were in the team’s city, if you wanted to watch the game, you had two choices. Either you could buy a ticket and see it in person, or you could watch it on a distant TV station. Some people drove to other cities to watch the game. It was cheaper to rent a hotel room and drive there, so that’s what some people did. But some people put up a big enough antenna so they could watch the game at home, and that’s what Buckwalter’s article told you how to do.

He explained a number of possibilities. If you already had an outdoor antenna, then what you needed was a rotor, so you could steer it toward the city where the game was playing. Of course, your picture might still be full of snow, so putting a pre-amp on the mast might do the trick.

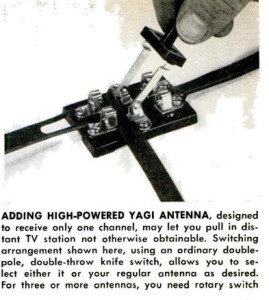

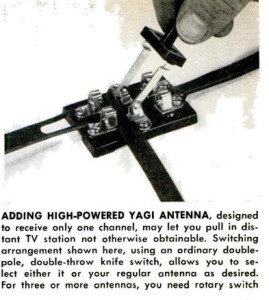

Particularly avid sports fans could purchase a separate yagi antenna tuned to the channel carrying the game, and point that toward the out-of-town station. They could install a knife switch like the one shown here. On game day, they would switch on the yagi. On other days, you would switch back to the antenna receiving the local channels.

Particularly avid sports fans could purchase a separate yagi antenna tuned to the channel carrying the game, and point that toward the out-of-town station. They could install a knife switch like the one shown here. On game day, they would switch on the yagi. On other days, you would switch back to the antenna receiving the local channels.

To demonstrate the art, the article carried screen shots showing a baseball game broadcast on Channel 8 in New Haven, CT., being pulled in by an antenna in New York City. With an outdoor antenna a pre-amp, the picture quality was actually better than a New York channel with an average antenna setup.