Bottom Line: Relatively expensive, but good way to add some variety to your survival kit.

We’ve previously reported about the importance of a car winter survival kit, to make sure you have enough food in the car to keep yourself reasonably comfortable if stranded. Recently, for example, a winter storm stranded motorists on Interstate 95 in Virginia for over 24 hours. As we showed previously, the kit in our car contains mostly dry food, and we have water and a means of cooking in the car.

One item that was lacking from the original kit was meat, or any type of protein for that matter. I corrected that after Christmas by buying a Hickory Farms meat and cheese gift package at a steep after-Christmas closeout discount, similar to the one shown at right.

One item that was lacking from the original kit was meat, or any type of protein for that matter. I corrected that after Christmas by buying a Hickory Farms meat and cheese gift package at a steep after-Christmas closeout discount, similar to the one shown at right.

Another item recently caught my eye, and that was the pouch of Great Value Pulled Pork in BBQ Sauce from Walmart. Its already cooked, so it only needs to be warmed up. Of course, in an emergency, it could be eaten cold. It’s best on a bun, but any kind of bread or crackers would work fine. You could also eat it right out of the pouch, or together with one of the other dishes in the survival kit, such as the rice or mashed potatoes.

Another item recently caught my eye, and that was the pouch of Great Value Pulled Pork in BBQ Sauce from Walmart. Its already cooked, so it only needs to be warmed up. Of course, in an emergency, it could be eaten cold. It’s best on a bun, but any kind of bread or crackers would work fine. You could also eat it right out of the pouch, or together with one of the other dishes in the survival kit, such as the rice or mashed potatoes.

To test it at home, I was originally going to heat it up in the microwave, but I realized that I should just warm it up as I would in the car. Since I have in the survival kit an emergency stove and a pan, I decided to duplicate this at home. To keep from getting the pan dirty, I heated up water and simply placed the pouch in the water. Of course, in an emergency, if water is short, you can still use the water for drinking or cooking. More likely than not, if I had to heat it up in the car while stranded, I would be using melted snow.

The finished product was better than I expected. It made a reasonably filling lunch, and in an emergency, a hot sandwich (or even just hot meat out of the pouch) would seem luxurious.

This product wouldn’t be viable for a large portion of your emergency food storage. The 2.8 ounce pouch cost $1.28. It provides 11 grams of protein, and only 130 calories. By contrast, a jar of peanut butter, for only a little bit more money, provides 2520 calories and 98 grams of protein. According to Harvard University, the recommended daily protein intake is 0.36 grams per pound. So a person weighing 150 pounds should get about 54 grams per day. This means that for long-term storage, the peanut butter is a much better value. But for a day or two, the pulled pork would add a few calories to your diet, provide a welcome hot meal, albeit a small one, and provide you with some protein. And it’s quite possible that the contents of the car witner survival kit will be frozen when you need them. Thawing a pouch of meat is probably a lot easier than figuring out how to thaw a jar of peanut butter.

The package I bought had a “best by” date of November 2024, almost three years in the future. So I’ll definitely be tossing some in the car survival kit. I hope I don’t have to use them until a future family survival picnic.

Incidentally, if the package looks familiar, that’s because this type of packaging is also used for tuna, another possible choice for the survival kit.

Incidentally, if the package looks familiar, that’s because this type of packaging is also used for tuna, another possible choice for the survival kit.

Some links on this site are affiliate links, meaning this site earns a small commission if you make a purchase after clicking the link. However, the Walmart link above is not an affiliate link.

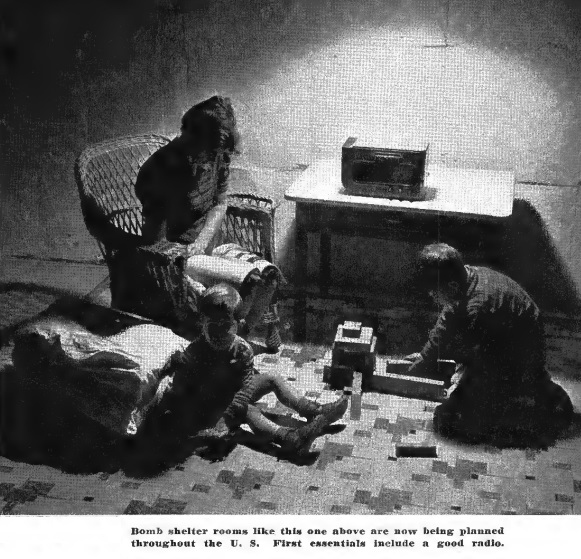

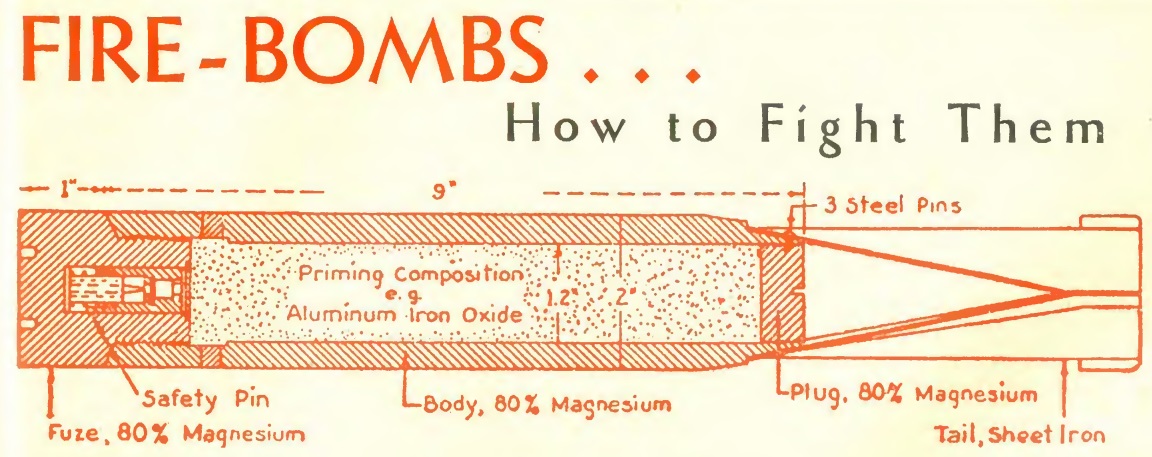

Eighty years ago today, according to the January 24, 1942, issue of Radio Guide, fire bombs were “ugly, dangerous weapons the enemy will eventually try to use right here in the U.S.A.” According to the magazine, hundreds of such bombs, each weighing only a couple of pounds, could carpet an area, causing particular damage if they hit the roof or attic of a building. Bing Crosby, therefore, took a few minutes out of the Kraft Music Hall program to allow Maj. John S. Winch to discuss how to deal with the threat.

Eighty years ago today, according to the January 24, 1942, issue of Radio Guide, fire bombs were “ugly, dangerous weapons the enemy will eventually try to use right here in the U.S.A.” According to the magazine, hundreds of such bombs, each weighing only a couple of pounds, could carpet an area, causing particular damage if they hit the roof or attic of a building. Bing Crosby, therefore, took a few minutes out of the Kraft Music Hall program to allow Maj. John S. Winch to discuss how to deal with the threat.