The reception problem and the final antenna.

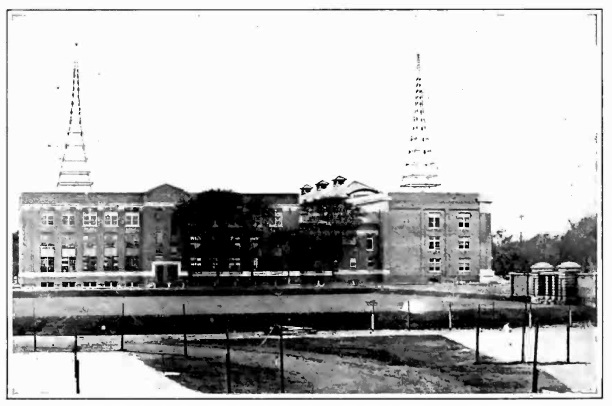

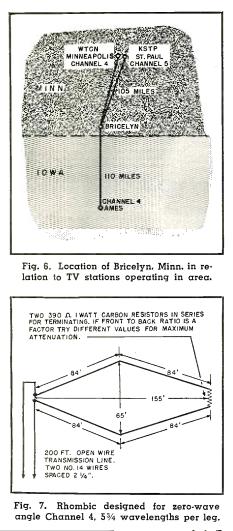

In 1950, Richard J. Buchan of Bricelyn, Minnesota, was apparently an avid basketball fan, and enjoyed following the Minneapolis Lakers. And he was apparently tantalyzed by the fact that the Lakers were carried on Channel 4 in the Twin Cities (then WTCN-TV), 105 miles to the north. WTCN also carried the state basketball tournament, and Buchan set out on a quest to pull those signals into his living room.

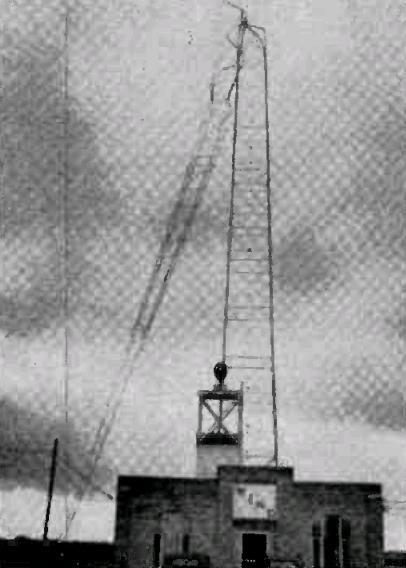

His quest had actually begun when KSTP came on the air on Channel 5 from St. Paul. Buchan was a ham (W0TJF), and “after studying antenna books and experimental charts put out by the FCC,” he came to the conclusion that KSTP would be putting out, at most, a 2.5 microvolt signal as far away as Bricelyn. He also knew that a 250 microvolt signal would be required for solid reception, a whopping 40 dB of gain. He set out on a yearlong quest to get those 40 dB of gain, and a “small set was purchased and connected up.” He initially began working on Yagi antennas and preamplifiers, and described his experimental quest in detail in an article in the October 1950 issue of Radio News.

Since he lacked any test equipment, he rigged a VTVM up to his television to serve as an S-meter, and set about experimenting. The Yagis and preamplifiers he tested were never enough to give him the elusive 40 dB of gain. In particular, to get sufficient gain from the Yagis, he found that the bandwidth was too narrow. If he maximized the gain for the audio, the video suffered, and vice versa. The problems were compounded by the entrance of Channel 4 to the airwaves with the elusive basketball games. He was soon resigned to the need for four Yagis, tuned for sound and picture on the two channels.

Much to his dismay, WOI-TV in Ames, Iowa, came on the air on Channel 4. Unfortunately, Ames was almost exactly 180 degrees away from Minneapolis, meaning that he now also had to worry about the front-to-back ratio of the Yagi. And by designing it for better front-to-back ratio, he lost gain. (Buchan reported that he made no attempt to tune in WOI, since it didn’t broadcast the elusive basketball games. As far as he was concerned, the Iowa station apparently represented nothing other than interference.)

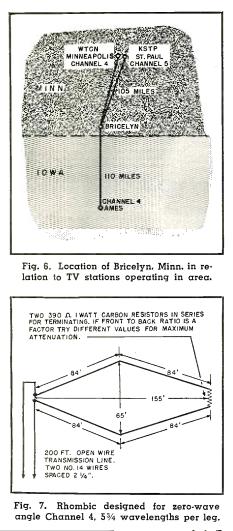

After some more study, he finally decided to abandon the Yagis and instead go with a Rhombic, which would have a theoretically infinite front-to-back ratio, but still have sufficient gain to pull in the elusive basketball games. Fortunately for Buchan, he had a large field across the road where he could install the antenna, which measured 155 feet in length, pointed toward the Twin Cities. Even though the final rhombic was actually lower than the Yagis, it performed well. Other than “an occasional gurgle in the sound,” the QRM from WOI was eliminated.

Presumably, the antenna continued to function well until the Lakers left Minneapolis in 1959.

Buchan, whose amateur call sign expired in 1998, also published more detailed construction details in Rhombic TV Antennas in 1951.

Click Here For Today’s Ripley’s Believe It Or Not Cartoon