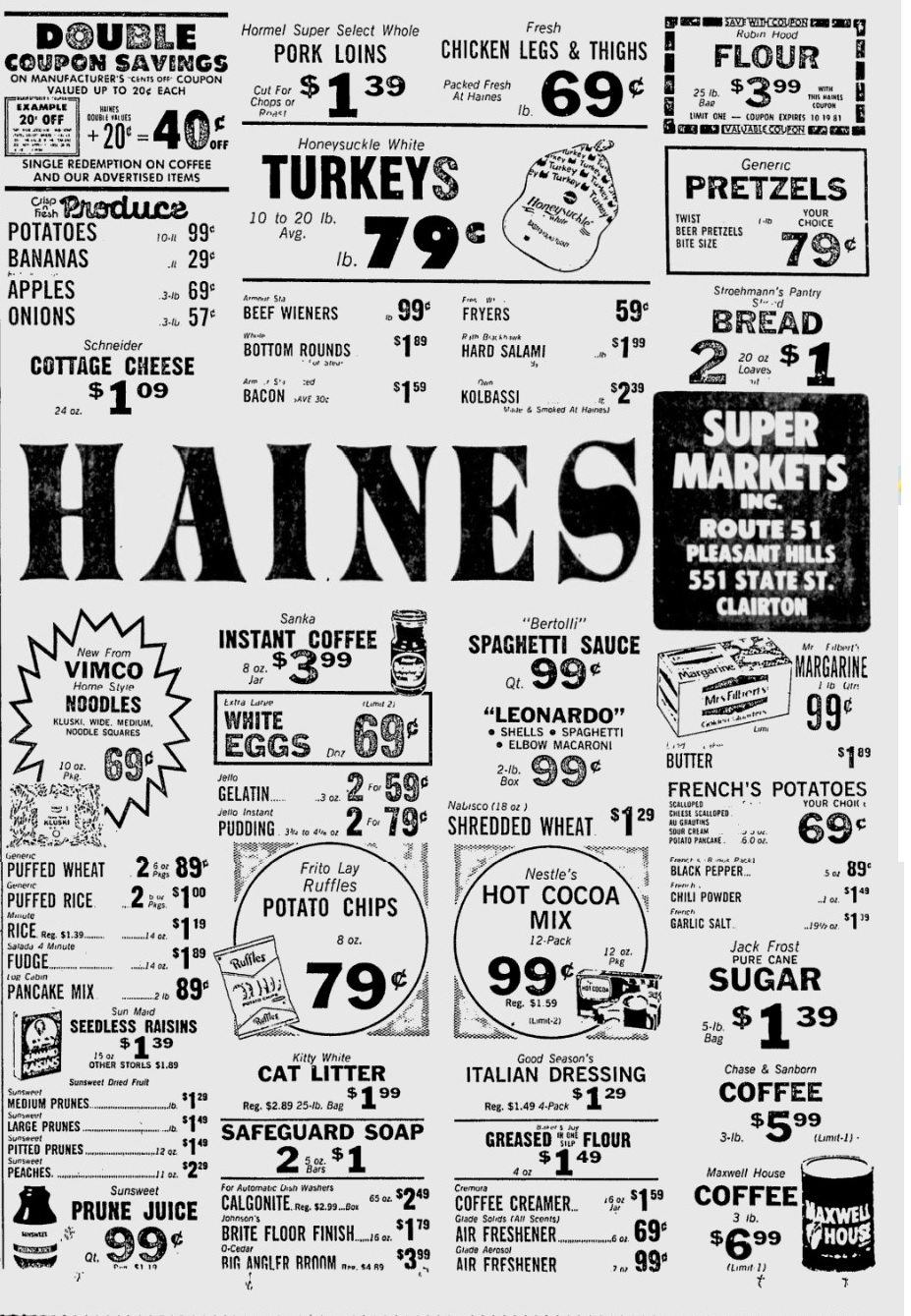

I find this ad intriguing on a number of levels. This particular instance is from 80 years ago this month, from the October 1941 issue of Popular Science. (You can click on either image to see a full size view of that page.)

Presumably, the publisher was able to make enough money to pay for two full pages in a national magazine by selling a five-volume set on mathematics for $8.95 over three months ($166.56 in 2021 dollars, according to this inflation calculator). Somehow, I doubt if they would have enough takers today.

The title of the series is “Mathematics for Self Study,” and it gets more curious when you consider the five individual volumes. They cover arithmetic, algebra, geometry, trigonometry, and calculus. One would think that the prospective customers for the arithmetic volume would have little overlap with the ones buying the calculus book, but here they are, offered as a package deal.

The author is James Edgar Thompson, of the Department of Mathematics of Pratt Institute in Brooklyn.

Even though it seems odd at first, there does appear to be a continuity between the books. The first volume, for example, appears to be much more than a primer on the subjects that were covered in elementary school. According to the ad, the arithmetic text starts with a quick review of principles, but then “presents all the special calculation methods used in business and industry which every practical man should know.”

The practical value of the set is stressed throughout the ad. The algebra book shows how to solve problems which are “involved in all military and industrial work.” Geometry covers all of the topics essential in drafting and engineering. Trigonometry covers the essentials for machine work, land surveying, mechanics, astronomy, and navigation. And the calculus book, “the branch of mathematics that deals with rate problems” allowed the solution of problems regarding areas such as efficiency and velocity. It noted that calculus was applied directly in the design of rifles and cannon.

The preface of the calculus volume explains the inherent continuity of the books:

In arithmetic we study numbers which retain always a fixed value (constants). The numbers studied in algebra may be constants or they may vary (variables), but in any particular problem the numbers remain constant while a calculation is being made, that is, throughout the consideration of that one problem.

There are, however, certain kinds of problems, not considered in algebra or arithmetic, in which the quantities involved, or the numbers expressing these quantities are continually changing. Many such examples could be cited; in fact, such problems form the greater part of those arising in natural phenomena and in engineering. The branch of mathematics which treats these methods is called the calculus.

I found a few modern reviews of these books, and almost without exception, the reviews are overwhelmingly positive. I’ve seen a few complete sets of the books for sale, for hundreds of dollars. However, for those wishing to acquire a set, it can be done economically. The same set of books was published over many years, and there are slight variations of the titles. The set sold in 1941 was entitled “for self study,” but later editions seem to have adopted “for the practical man” as the title. As far as I can tell, there were few changes, so Arithmetic for Self Study is probably essentially identical to “Arithmetic for the Practical Man.”

If you don’t mind a bit of variation, you should be able to find all five volumes at a reasonable price. The links below should help you find them. In many cases, the prices of different editions can vary considerably, so you’ll want to check all of the links below before placing an order.

The set was published by the D. Van Nostrand Company, which I believe is most famous for its behemoth Van Nostrand’s Scientific Encyclopedia. Of course, if you want to read all of the books at no cost, they are available in many public libraries. You can find them at Worldcat, and your local library should be able to get them with interlibrary loan.

The set was published by the D. Van Nostrand Company, which I believe is most famous for its behemoth Van Nostrand’s Scientific Encyclopedia. Of course, if you want to read all of the books at no cost, they are available in many public libraries. You can find them at Worldcat, and your local library should be able to get them with interlibrary loan.

Some links on this site are affiliate links, meaning this site earns a small commission if you click on the link and make a purchase.

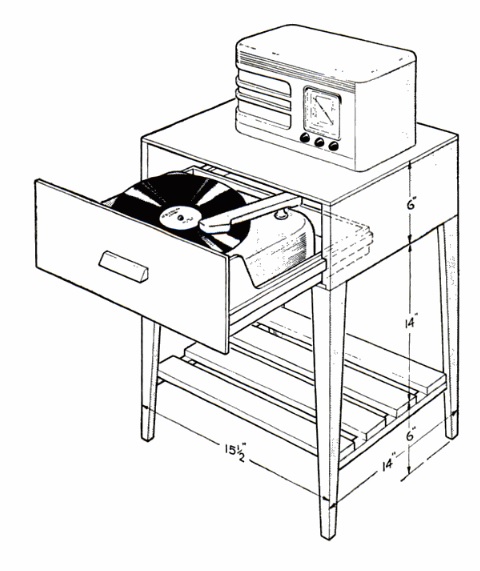

The October 1941 issue of Popular Science showed how to put together this radio-phonograph stand. The phonograph was placed in a drawer, not just for aesthetics, but to improve its performance by muffling the needle scratch and motor noise.

The October 1941 issue of Popular Science showed how to put together this radio-phonograph stand. The phonograph was placed in a drawer, not just for aesthetics, but to improve its performance by muffling the needle scratch and motor noise.