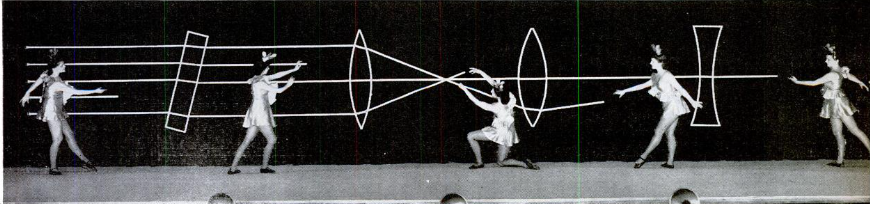

Students with artistic sensitivities might feel intimidated by the science fair, but they needn’t be. By recreating all or part of this 1944 demonstration, such a student can wow the audience with a ballet performance, demonstrate the principles of refraction of light, and take home the blue ribbon, undoubtedly to the consternation of the science nerds who thought they had no competition.

The original 1944 version was put on by Bausch & Lomb Optical Co. for its employees, to demonstrate the scientific principles used in the bomb sight components the company was making. They put together a ballet-like performance set to music, while the dancers pulled white ribbons through the lenses, demonstrating the path of light.

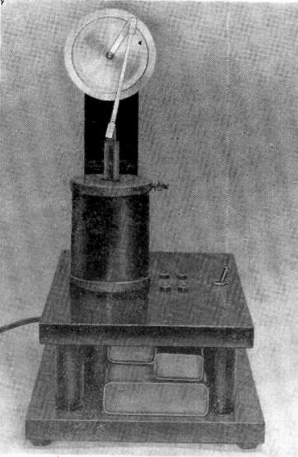

Of course, this display takes a great deal of preparation. For students who are desperately searching for a project the night before the science fair, try our earlier project demonstrating the same principles, one that can be whipped together the night before.

A complete description, along with more pictures, can be found in the April 17, 1944 issue of Life magazine.