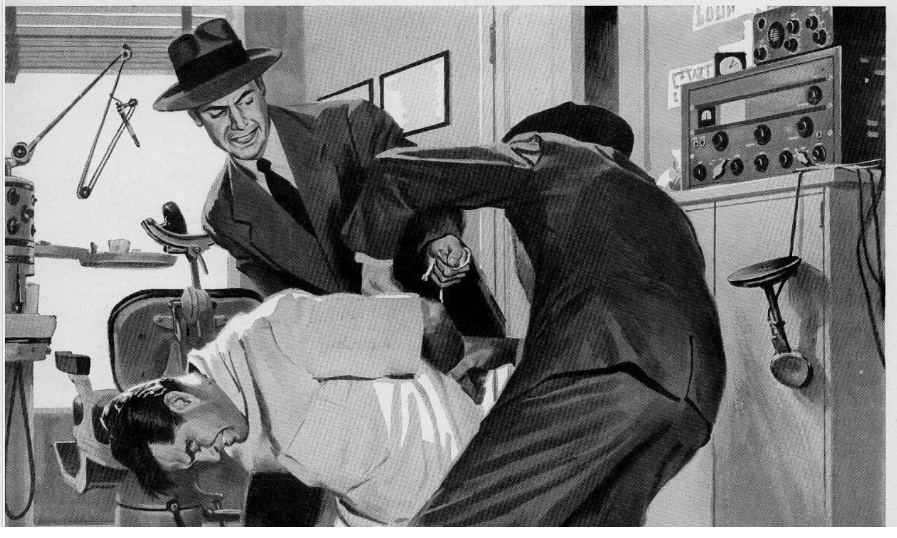

Seventy years ago this month, the December 1951 issue of Boys’ Life carried a feature entitled “SWLing is Swell,” pointing out all of the fun that can be had by shortwave listening, primarily to the ham bands. The article began with an incident shown in this dramatic illustration, of the robbery of dentist and ham radio operator Dr. Phillip Weintraub.

Seventy years ago this month, the December 1951 issue of Boys’ Life carried a feature entitled “SWLing is Swell,” pointing out all of the fun that can be had by shortwave listening, primarily to the ham bands. The article began with an incident shown in this dramatic illustration, of the robbery of dentist and ham radio operator Dr. Phillip Weintraub.

The two well-dressed robbers barged into Dr. Weintraub’s office, in which he luckily had his ham station set up. In a stroke of luck, he was in the middle of transmitting, and left the transmitter turned on while the robbery was taking place.

The thieves were disappointed that the dentist had no money other than five dollars in his wallet, and there was no gold on the premises. The tied him up, stashed him in a closet, and departed.

As luck would have it, however, the dentist’s wife, Evelyn Weintraub, was at home, and just happened to be listening to her husband’s station. She quickly called the police, and then raced to the office, arriving before the first squad car. She pounded frantically at the closet door, and one of the responding officers was able to take the door off its hinge. The police sergeant later told her, “you’d be a widow right now if you hadn’t heard those holdup men over the radio and reported it.”

The story sounds a bit suspect, but there’s enough corroboration to say that it is probably true, and probably took place in about 1937. There was indeed a Philip and Evelyn Weintraub in Chicago, as shown in the 1940 census. Indeed, his house at 3252 W. Victoria Street is a Chicago landmark complete with its own Wikipedia page.

And the 1952 call book shows Philip Weintraub listed twice, once as W9SZW at 3252 Victoria, and as W9TMQ at 201 South Pulaski Road. That address is currently a vacant lot, but it’s in a commercial district, and it seems like a plausible spot where a dental office would have been located 70 years ago. The callbook also lists a Royd L. Weintraub as being licensed as W9PZO at the home address. In the 1940 census, Royd is listed as being 2 years old, so he would have been about 14 years old in 1952. You can see the younger Weintraub’s biography at this link.

Thus it appears the doctor had a secondary station location licensed at his office, and the story sounds more plausible. Indeed, the incident is recorded in more detail in the 1941 book Calling CQ by Clinton DeSoto, W9KL, which includes much the same story, with the added detail that Weintraub was in QSO with W9JFF or (or possibly W9JJF), who was “frantic but impotent,” as his heart pounded madly listening to the drama unfold. DeSoto’s account notes that the doctor stayed late at the office, having told his wife, reportedly a dark haired sultry beauty, that he would be late, and invited her to listen in, as she often did.

The other reference I found to this story was a brief mention in the July 1937 issue of Radio News. Apparently, WMAQ ran a midnight program consisting of dramatic reenactments of “important events in amateur radio,” sponsored by Hallicrafters. The magazine shows a reenactment of the holdup, and notes only that “Dr. Weintraub was saved due to the presence of a transmitter in his office.”

I would stay up until midnight to listen to that program, and it’s a shame that it’s no longer on the air.