A hundred years ago, if you were located 26 miles across the sea (40 kilometers, for those in leaky old boats) at Avalon, Santa Catalina Island, California, you could enjoy the luxury of telephone service with any telephone in the United States, thanks to the radiotelephone service operated by Pacific Telefone and Telegraph Co., as described in the March 1921 issue of Radio News.

A hundred years ago, if you were located 26 miles across the sea (40 kilometers, for those in leaky old boats) at Avalon, Santa Catalina Island, California, you could enjoy the luxury of telephone service with any telephone in the United States, thanks to the radiotelephone service operated by Pacific Telefone and Telegraph Co., as described in the March 1921 issue of Radio News.

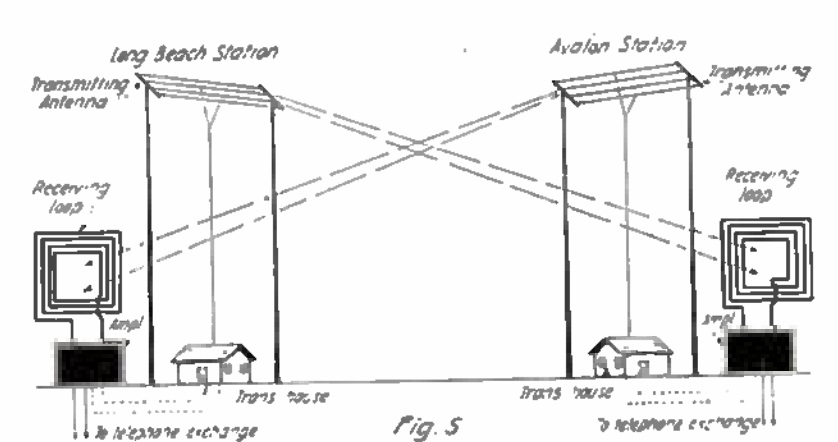

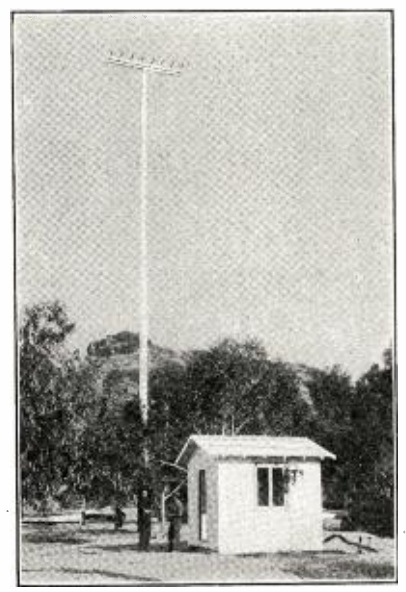

The system consisted of stations KUVX at Avalon and KUXT at Long Beach. A complicating factor was the presence of naval station NZL, also located at Avalon. To avoid interference, the radiotelephone receiving station employed a wave trap to null out NZL’s frequency. The article gives the radiotelephone wavelength of 425 meters (706 kHz). The system was full duplex, meaning that there would be different transmitting and receiving frequencies. Since the 425 meter wavelength is discussed in conjunction with the wave trap on the receiving antenna, it appears that the Long Beach station transmitted on 425 meters, and Avalon transmitted on a different frequency.

The author described an interesting catch for an SWL as part of a test conducted by the Avalon station. He listened in on a conversation from Avalon to the mainland, which was carried by the transcontinental telephone lines to New York, where the call was carried by another radiotelephone station to a ship in the Atlantic. The author reported that the voice was a little distorted, but could be clearly heard throughout the ten minute test.

The Avalon station was powered by a motor generator, and to avoid having to restart the power, the carrier was left on 14 hours a day, with calls to and from local hotels, stores, and residents carried as needed. A licensed radio operator oversaw the transmitter, connected to an eight-wire antenna, and receiver, connected to a loop antenna. A telephone operator put through the calls, presumably with another operator at the Long Beach side of the circuit doing the same.

The system was able to transmit telegraph signals simultaneously with telephone conversations without interference. This was accomplished by “superimposing a high pitched harmonic on the carrier wave.”

A more detailed technical description of the system can be found in the December 1921 Proceedings of the IEEE. You can also find additional references at Wikipedia, which notes that the system was replaced by a submarine cable in 1923, ending the possibility of radio listeners being able to tune in to telephone conversations.