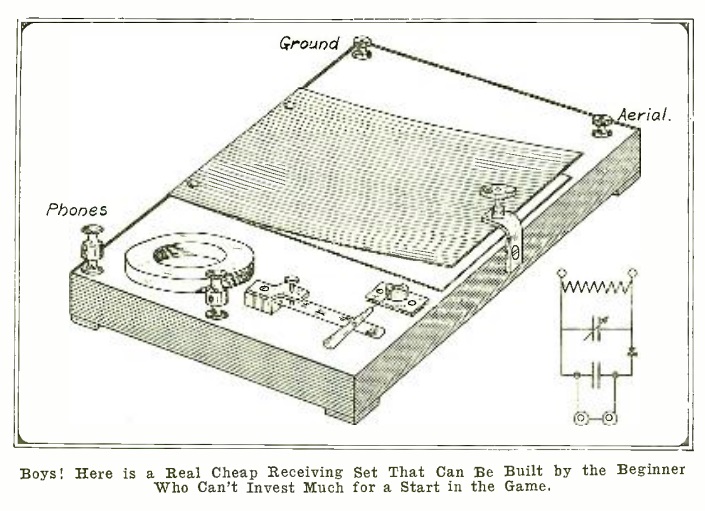

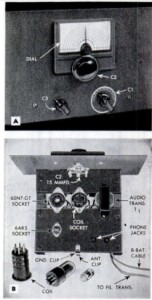

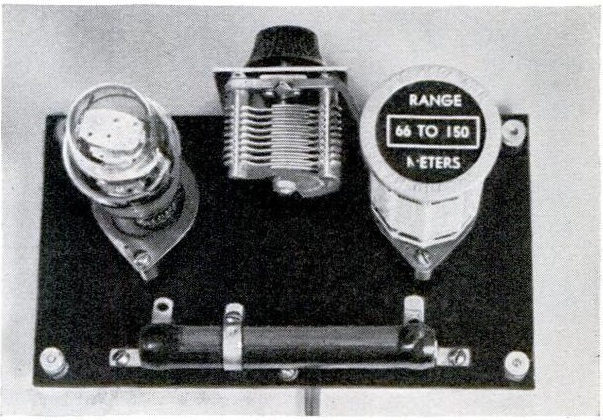

Seventy years ago, this gentleman was pulling in a program on the standard broadcast band with headphones, but in the following months, he would be able to listen to the shortwaves with loudspeaker volume. He is shown here listening to the first iteration of a progressive receiver featured in the May 1951 issue of Popular Mechanics. In coming months, additions would be made to the set to allow shortwave reception and loudspeaker operation.

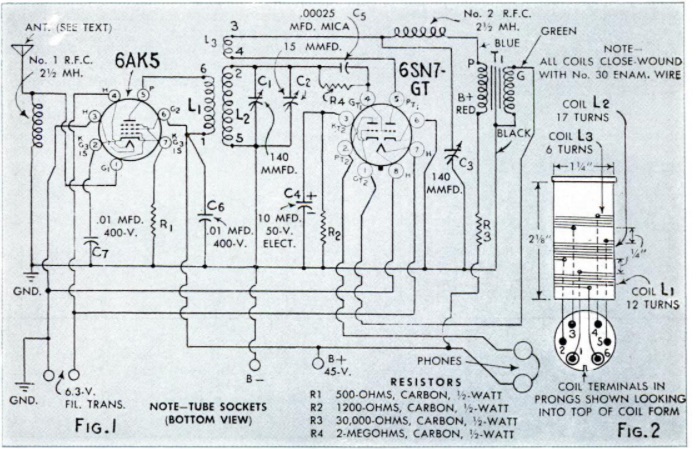

The set was battery powered, and the magazine pointed out that there were a number of good reasons for putting together a battery set. The most important reason was having a set capable of operation independent of the power lines for civil defense purposes. The circuit was also simpler and saved having to deal with baffling power supply troubles.

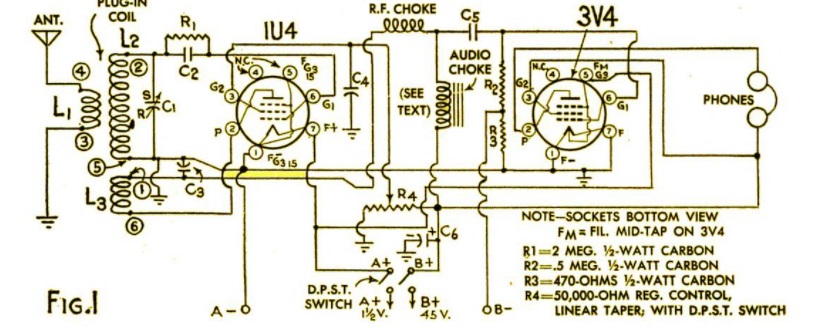

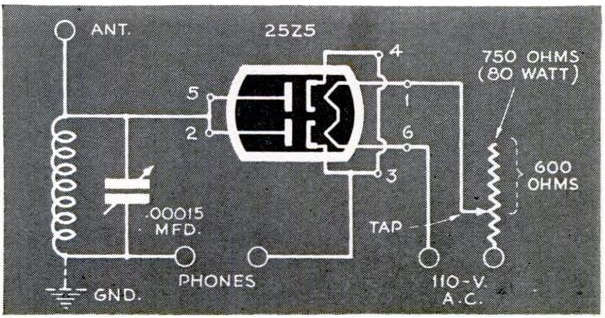

This version of the set used a 1U4 tube as regenerative detector followed by a 3V4 audio amplifier. An indoor antenna and ground could be used for local statioms, but an outdoor antenna would be best for long distances. “With a battery-operated emergency receiver of this description, you are not cut off from outside news and vital civil-defense information should local power sources fail. Most of us do not realize how important this could be.” You would, of course, need to keep fresh batteries on hand. The circuit called for flashlight batteries for the filament, and a 45 volt battery supplying the B+.