Welcome to OneTubeRadio.com. This blog covers a variety of subjects, including radio history, Minnesota history, World War I, World War II, and scouting.

- Jump to 1922 Aeronautical Wedding

- Jump to Ye Old Mill at 100 Years

- Jump to Radio at the Minnesota State Fair

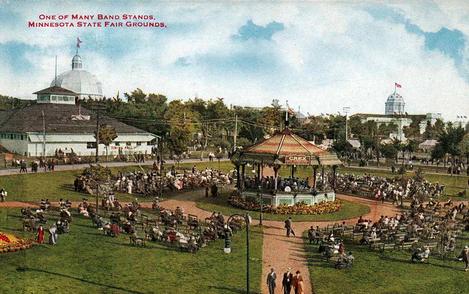

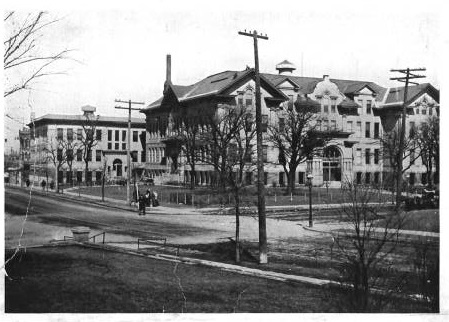

Today, we offer these images of the Minnesota State Fair as it appeared a hundred years ago in 1915. The scene above is the bandstand. Visible in the background is the dome of the Agriculture Building. A closer images of this building is also shown here, from the fair’s 1915 annual report.

1922 Aeronautical Wedding

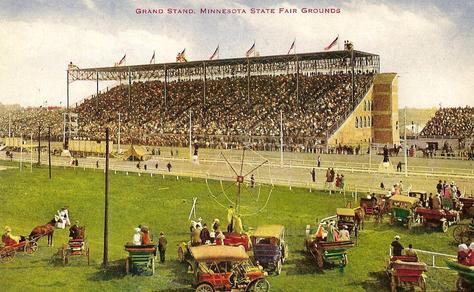

The grandstand, in the 1915 postcard shown below, is immediately recognizable to a modern visitor. As previously reported here, in 1922, the grandstand served as the wedding venue of Edwin Moline and Zelma Olson, who were married aboard an airplane flying above the grandstand. The presiding minister, Rev. E.A. Jordan, at 220 pounds, was too heavy to fit inside the airplane along with the pilot, bride, and groom. Therefore, he officiated from a pagoda within the grandstand, receiving the couple’s vows by a radio which was carried aboard the plane.

Ye Old Mill at 100 Years

Ye Old Mill, 2008. Photo, placeography.org, Licensed under the Creative Commons

Attribution-ShareAlike License v. 3.0.

This year, the “Ye Old Mill” attraction at the Minnesota State Fair celebrates its 100th Anniversary. Many visitors are surprised to learn the nearly identical attractions with the same name at the Iowa State Fair (dating to 1921) and Kansas State Fair (also dating to 1915).

Radio at the Minnesota State Fair

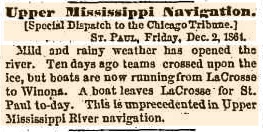

Radio has a long tradition at the Minnesota State Fair. Indeed, the photo of the grandstand shows on the field what certainly appears to be a wireless antenna of some sort, although I don’t have any details of the old image. In 1914, the fair’s governing board considered a proposition made by one Philip Edelman of St. Paul for the installation of a wireless station at an esimated cost of $200. The board decided to continue discussions with Edelman as to whether such an exhibit could be made in a future year at less cost.

The Minneapolis sign of Sterling Electric Company, 1920 state fair exhibitor. Google books.

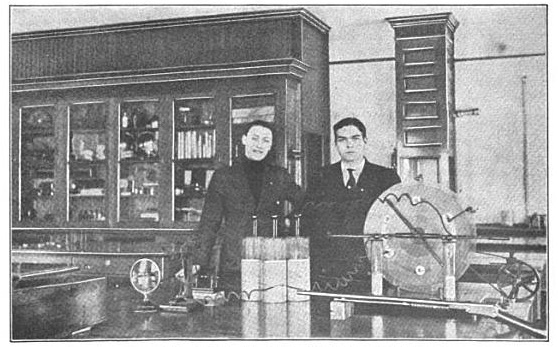

One of the earliest references I could find to radio at the State Fair was the December 1920 issue of Electrical Contractor Dealer, which detailed the experiences of the Sterling Electric Company of Minneapolis. At the 1920 Fair, the company had a large booth in the Electrical Building which included a wireless station that sent and received messages daily. The company followed up with a Saturday morning class in wireless telegraphy, in which there was considerable interest.

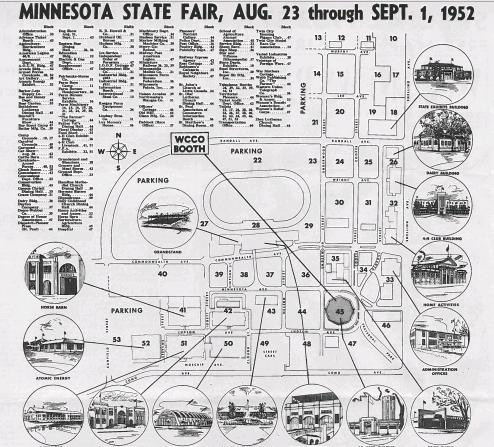

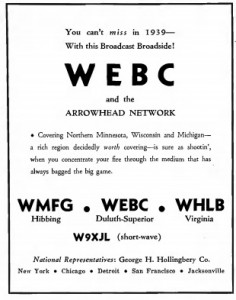

Shortly thereafter, the company, along with the Journal Printing Company, was the licensee of one of the area’s first broadcast stations, WBAD. That license was issued on April 25, 1922, according to the May 1922 issue of Radio World. It is likely, therefore, that the honors for being the first radio station at the fair go to WBAD. Since then, of course, local broadcasters have a long history of broadcasting from the fair. The image below from a WCCO promotional item shows the station’s then location in the Agriculture-Horticulture building.

Read More at Amazon

Click Here For Today’s Ripley’s Believe It Or Not Cartoon ![]()