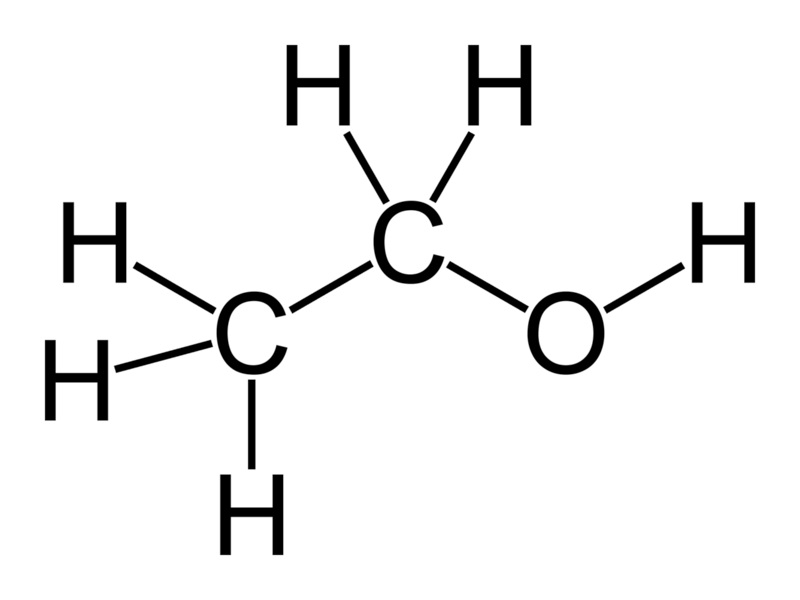

Gasoline versus Ethanol

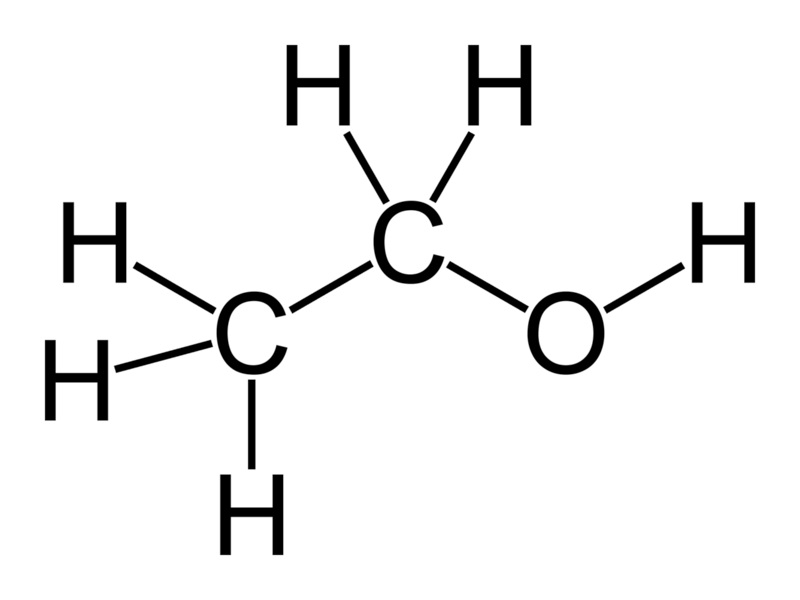

Shown above is a molecule of ethyl alcohol, also known as ethanol. If you ignite it with a spark, it will burn. This is not rocket science. (Come to think of it, though, if you use it as rocket fuel, then it is rocket science.) Gasoline (or petrol, as our friends across the pond like to call it) is a mixture of molecules, most of which look very similar to the one above. If you ignite it with a spark, it will also burn. The difference, however, is the “O“. Gasoline doesn’t have any oxygen atoms. To burn it, you need to supply all of the oxygen from another source. Fortunately, that’s easy to do, since we live in an atmosphere consisting partly of oxygen, and it’s free for the taking.

But this means that for a given amount of fuel, the ethanol will have less energy content: If you burn gasoline, you can use the free oxygen that is floating around. If you use ethanol, then you are paying for some of the oxygen, which you could have gotten for free.

For this reason, I’ve heard many people explain that you shouldn’t use ethanol as fuel, because your fuel mileage will be lower. But that’s not the end of the discussion: If you’re like me, you are really concerned about saving money, and your main concern is which fuel is cheaper.

A Real World Comparison Test

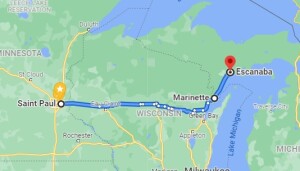

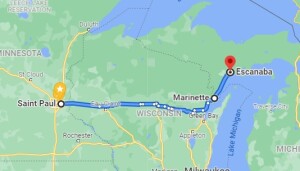

I’ve heard many persons express their opinion as to the relative fuel economy, but I’ve never heard anyone actually test it, so I decided to do so myself. I recently had to drive from St. Paul, MN, to Escanaba, MI, to do an FCC Great Lakes Ship Radio Inspection. I drove eastbound using e85, a mixture of approximately 85% ethanol and 15% gasoline, and drove westbound with gasoline (which is actually e10, 90% gasoline and 10% ethanol). For the nitpickers, here are the conditions of the test:

I’ve heard many persons express their opinion as to the relative fuel economy, but I’ve never heard anyone actually test it, so I decided to do so myself. I recently had to drive from St. Paul, MN, to Escanaba, MI, to do an FCC Great Lakes Ship Radio Inspection. I drove eastbound using e85, a mixture of approximately 85% ethanol and 15% gasoline, and drove westbound with gasoline (which is actually e10, 90% gasoline and 10% ethanol). For the nitpickers, here are the conditions of the test:

To make sure I was able to purge almost all of the E85 from the system before the return trip, I tested the mileage from St. Paul, MN, to Marinette, WI, short of my final destination. I started with a full tank, and upon arriving in Marinette, I checked the cumulative mileage and then added about 6 gallons. I also added a few gallons in Escanaba, MI, about 56 miles away. When I arrived back in Marinette, I was down to about a quarter tank, at which point I filled with gasoline (actually, e10) for the trip home. So almost all of the e85 had been purged from the system for the trip home.

My vehicle is a 2014 Dodge Journey with the 3.6 liter 6 cylinder engine. The EPA estimated highway mileage is 25 MPG with gasoline, and 18 MPG with e85. The two endpoints have similar elevations (795 feet in St. Paul, versus 594 in Marinette). Winds on the day of my trip were light, and whenever I did see flags moving in the breeze, the prevailing wind seemed to be from the north. So there should be no effect from a headwind or tailwind. I took an identical route both directions, mostly over four lane freeways, but a small portion over county highways suggested by Google. In other words, the driving conditions both directions were more or less identical. The average mileage reading was taken from the car’s computer, which was reset after each fill-up.

The average mileage using e85 was 21.6 MPG. The average mileage using gasoline (actually e10) was 26.4 MPG. As noted above, the mileage with ethanol was lower, since the fuel has a lower energy content. The real question is which fuel is cheaper.

To make the comparison fair, I’ll use the prices at the same station, the one where I bought the e85: The e85 cost $2.229 per gallon. In other words, it cost me $2.229 to drive 21.6 miles, or 10.32 cents per mile. (I actually used a loyalty card, which brought the cost down to $2.029 per gallon, or 9.4 cents per mile).

The gasoline I bought for the return trip cost $3.239 per gallon, since one gallon allows me to drive 26.4 miles, that means I spent 12.3 cents per mile. But in fairness, if I had bought that gas for the eastbound trip at the same place where I bought the e85, it would have cost $3.099 per gallon, which works out to 11.7 cents per mile.

In other words, it was cheaper to drive using the e85: 10.3 cents per mile versus 11.7 cents per mile. In other words, the e85 is 12% cheaper than using gasoline.

It should be noted that these figures are based upon the price at one particular station, a Holiday gas station. You can view the current prices at this station at this link. Some gas stations sell e85, but at a much smaller discount over the price of regular gasoline. In fact, I’ve occasionally seeing a station inexplicably selling e85 for more than the price of regular gasoline. Obviously, it makes no sense to buy to buy there. To be economical, the price of e85 needs to be below 21.6/26.4 = 82% the price of regular gas. In my case, the price of e85 was 74% the cost, and thus a clear bargain.

Other Considerations

There are a couple of other factors to keep in mind. Even though the name of the fuel is “e85” the exact blend can vary. During the winter months, the gasoline content is higher, and I have noticed that stations do not adjust the price based upon the exact mix. So during the winter, the e85 might be an even greater bargain.

Also, I have not measured it, but I have noticed that when I have a mixture that is around 50% ethanol and 50% gasoline, I don’t notice much mileage difference between it and 100% gasoline. So even though the energy content is lower, the actual effect on mileage might not be linear. It would be interesting to repeat this experiment with different blends.

I’m not sure of this, but I suspect that for applications requiring more power (such as towing), gasoline would have a greater advantage. But again, I’ve not tested this hypothesis.

And you will certainly have more range using gasoline than you would ethanol. So if cost isn’t an issue, but you need to drive as far as possible before refueling, then you will be able to drive 22% further by using gasoline.

I suspect that ethanol might have a greater cost advantage for high altitude driving. The reason why there is a lower energy content is because the fuel contains oxygen, which is available at no cost from the atmosphere. At higher elevations, the additional oxygen in the fuel might be an advantage.

Precisely because it has a lower energy content, ethanol also increases the octane rating of the fuel, so it is an inexpensive option for use in high compression engines.

Ideas for Young Scientists

If students are looking for an interesting science fair project, I hope my little experiment has given you some ideas. Even if you don’t have a driver’s license, you can recruit your parents to keep track of mileage when driving, and compare different fuels, or different types of driving, to see which is the most economical.

If students are looking for an interesting science fair project, I hope my little experiment has given you some ideas. Even if you don’t have a driver’s license, you can recruit your parents to keep track of mileage when driving, and compare different fuels, or different types of driving, to see which is the most economical.

Interestingly, I exceeded the EPA mileage estimates for both fuels. There was a time when the EPA estimates were overly optimistic, but I guess those days are gone.

But Ethanol Will Clog My Fuel Filter!

Someone will invariably claim that ethanol clogs fuel filters, and I want to explain what is really happening. Alcohol can mix with both water and gasoline. Water, by itself, cannot mix with gasoline. If you have 100% gasoline in your tank and some water is added, it is heavier than gasoline and will settle to the sump at the bottom of the tank, which is below the point where it can be drawn out by the fuel pump. It doesn’t do any harm there, as long as it stays below the level of the fuel intake. But it does dissolve dirt, and that dirt has nowhere to go but stay in the water.

Eventually, if water keeps getting added, it will continue to collect. If it ever gets up to the level of the intake, then this will be a problem, since water mixed with dirt will be going to the engine rather than gasoline. The fuel filter will clean out the dirt, but the engine will try to burn the water, and water doesn’t burn.

When ethanol was first added to gasoline in the U.S., this meant that it found its way, for the first time, into cars with water in the bottom of the tank. The alcohol allowed the water and dirt to mix with the gasoline. The dirt, which may have collected since the car was new, went into the fuel filter, as the filter was designed to do. This is how ethanol got a reputation for clogging fuel filters.

But now, virtually all gasoline sold in the U.S. contains at least 10% ethanol, and virtually every car on the road has been burning 10% ethanol for years. Water never gets a chance to build up in the tank. If there is dirt in the tank, it comes out constantly. Unlike the time the car got its first tank of ethanol, years’ accumulation of dirt is not coming out all at once to suddenly clog the filter. So after that initial shock, ethanol actually corrects the problem, and also prevents gas line freeze. In the days before ethanol fuel, in cold climates, people bought a product called Heet to prevent fuel line freezing. This consisted either of ethanol or isopropyl alcohol. Since ethanol is now included in the fuel, this is no longer necessary, and you rarely hear of gas lines freezing.

But now, virtually all gasoline sold in the U.S. contains at least 10% ethanol, and virtually every car on the road has been burning 10% ethanol for years. Water never gets a chance to build up in the tank. If there is dirt in the tank, it comes out constantly. Unlike the time the car got its first tank of ethanol, years’ accumulation of dirt is not coming out all at once to suddenly clog the filter. So after that initial shock, ethanol actually corrects the problem, and also prevents gas line freeze. In the days before ethanol fuel, in cold climates, people bought a product called Heet to prevent fuel line freezing. This consisted either of ethanol or isopropyl alcohol. Since ethanol is now included in the fuel, this is no longer necessary, and you rarely hear of gas lines freezing.

Some links on this page are affiliate links, meaning that this site earns a small commission if you make a purchase after clicking the link.

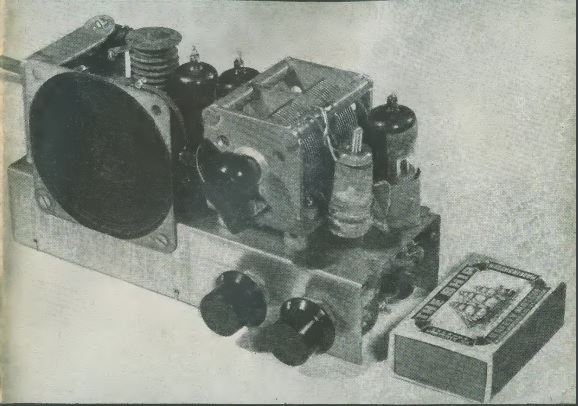

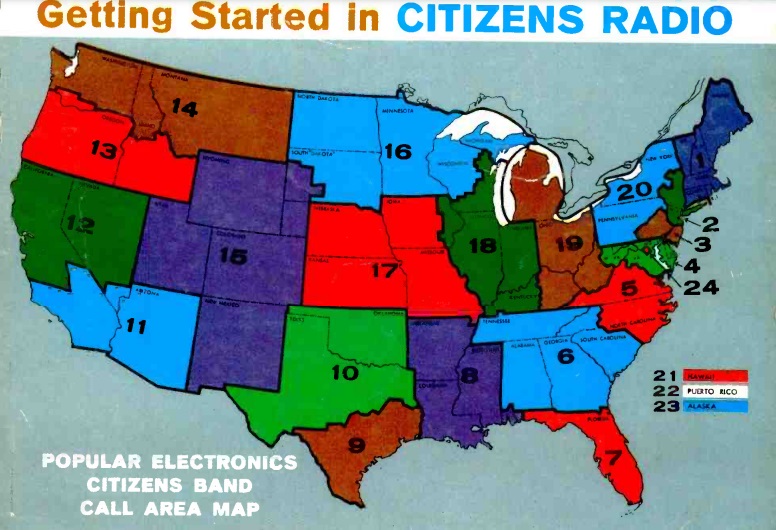

By 1961, it was clear that the 11 meter Citizens Band was a hit. Popularity hadn’t hit the frenzied levels of the 1970s, but it was becoming popular, especially by those with some background in electronics. The 27 MHz band had been allocated to Class D CB in 1958, and in three years, much equipment was available on the market.

By 1961, it was clear that the 11 meter Citizens Band was a hit. Popularity hadn’t hit the frenzied levels of the 1970s, but it was becoming popular, especially by those with some background in electronics. The 27 MHz band had been allocated to Class D CB in 1958, and in three years, much equipment was available on the market.