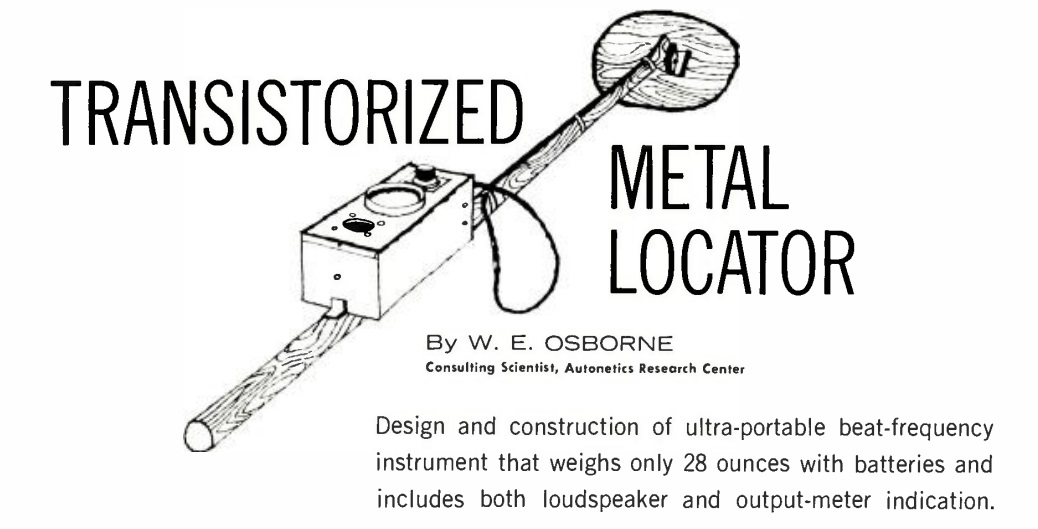

Sixty years ago this month, the March 1962 issue of Electronics World showed how to put together this five transistor metal detector, using either 2N188A or 2N524 transistors. While these PNP germanium transistors are probably no longer manufactured, there are New Old Stock (NOS) specimens still to be found. However, the circuit is quite common in cheap metal detectors, and it’s probably most cost effective just to buy one from one of the links below.

Sixty years ago this month, the March 1962 issue of Electronics World showed how to put together this five transistor metal detector, using either 2N188A or 2N524 transistors. While these PNP germanium transistors are probably no longer manufactured, there are New Old Stock (NOS) specimens still to be found. However, the circuit is quite common in cheap metal detectors, and it’s probably most cost effective just to buy one from one of the links below.

If you’re looking for a very basic kit to build, the final link below is a one-transistor oscillator, which you use in conjunction with an AM radio for a rudimentary metal detector.

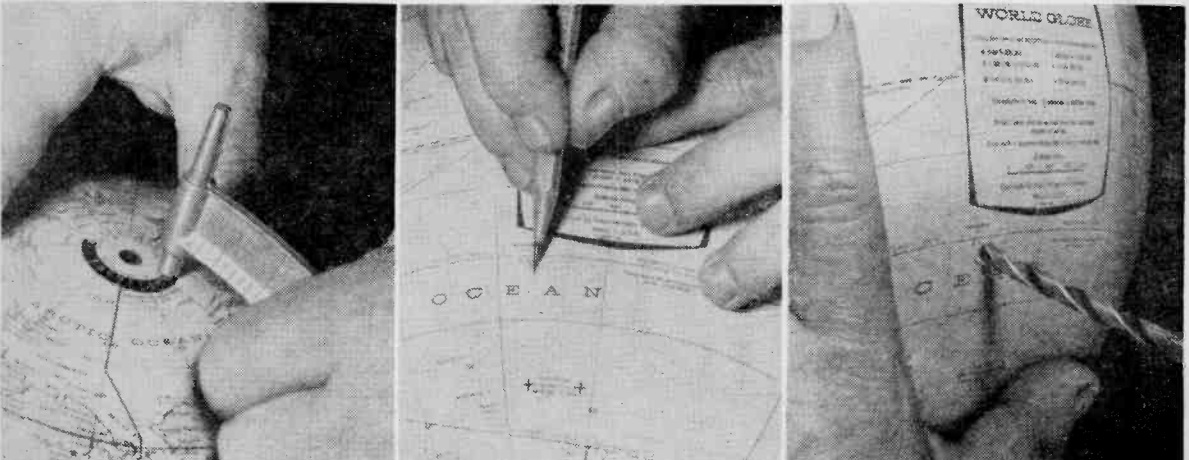

This type of metal detector is often sold as a toy, and the kids soon lose interest, or the parents confiscate it because of the annoying squeal. But they can actually work quite will, with just a bit of patience and practice.

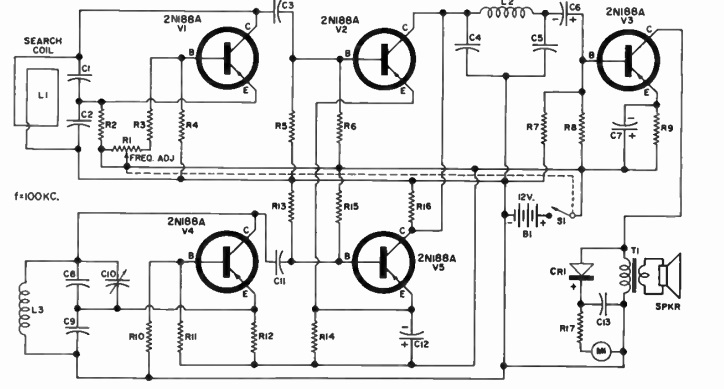

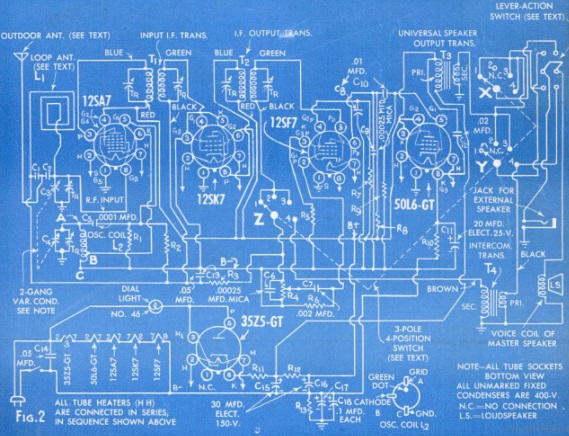

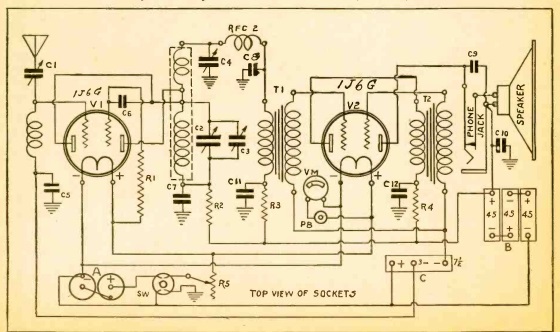

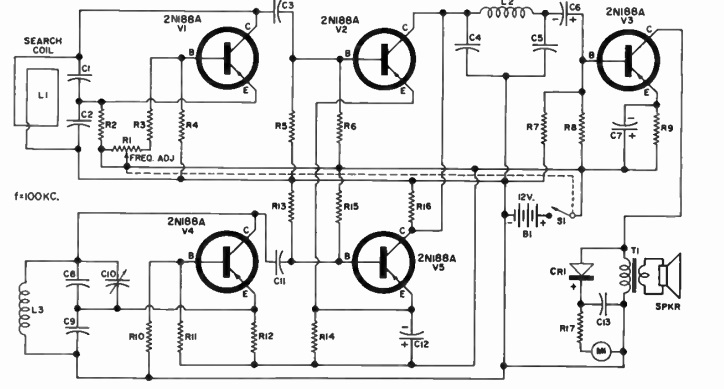

This beat-frequency circuit consists of two identical oscillators, both tuned to the same frequency of about 100 kHz. One of them uses a coil mounted inside the case, and the other uses the search coil. When a metallic object comes near the search coil, that oscillator changes frequency. You start by tuning both to the same frequency, meaning that they become “zero beat,” and no sound comes out of the speaker. But when one oscillator changes frequency, and audio tone is heard, its frequency being the difference between the two oscillators. As long as you tune it carefully to zero beat, this type of detector is very sensitive. They’re regarded as toys because most kids don’t bother with the careful tuning part.

The secret of using this type of metal detector is to practice. Toss some metallic objects on the floor, set the unit so that the tone just barely disappears, and then see how it reacts to those objects. You’ll normally find that occasional re-tuning is necessary as the batteries get lower.

Some links on this site are affiliate links, meaning that this site earns a small commission if you make a purchase after clicking on the link.