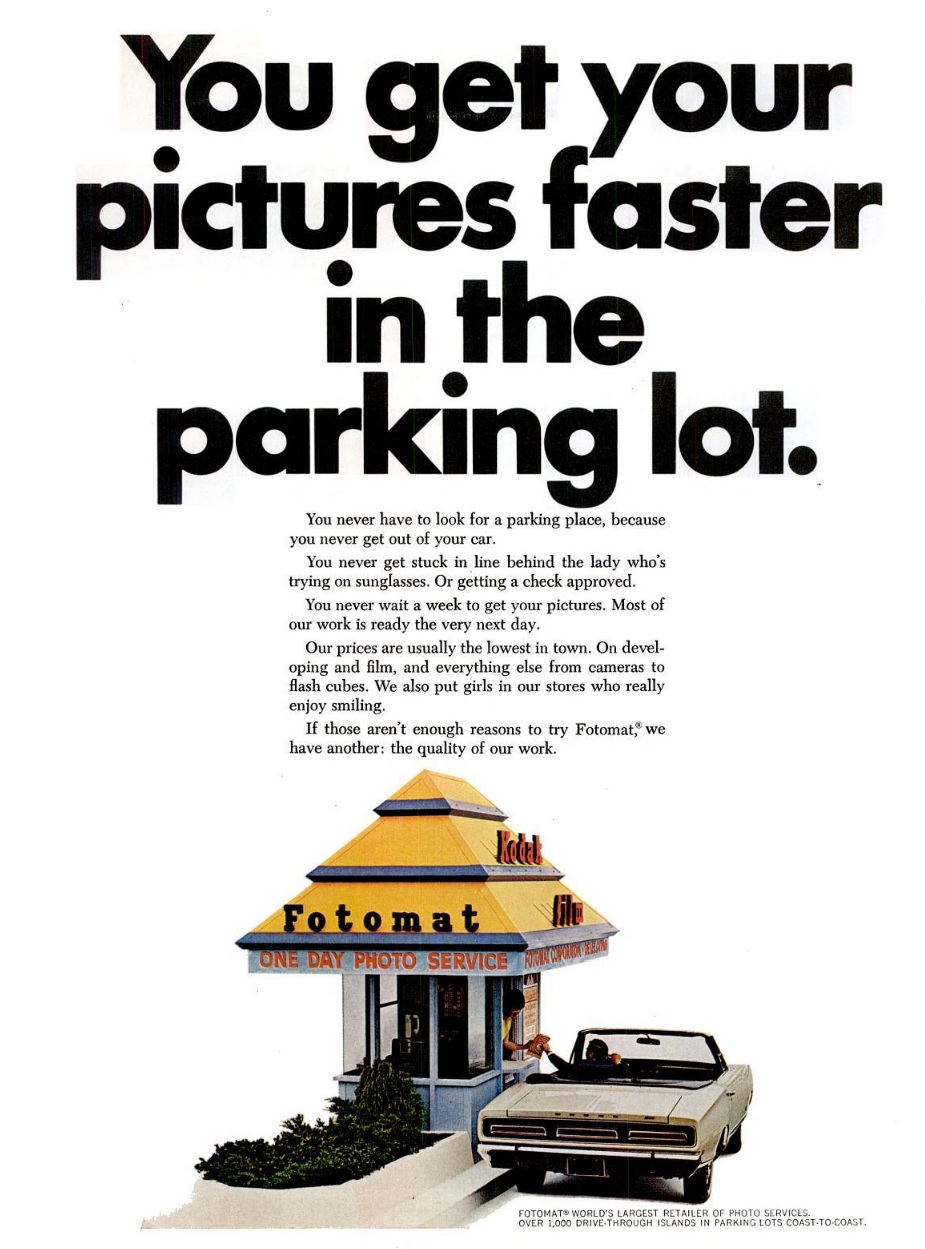

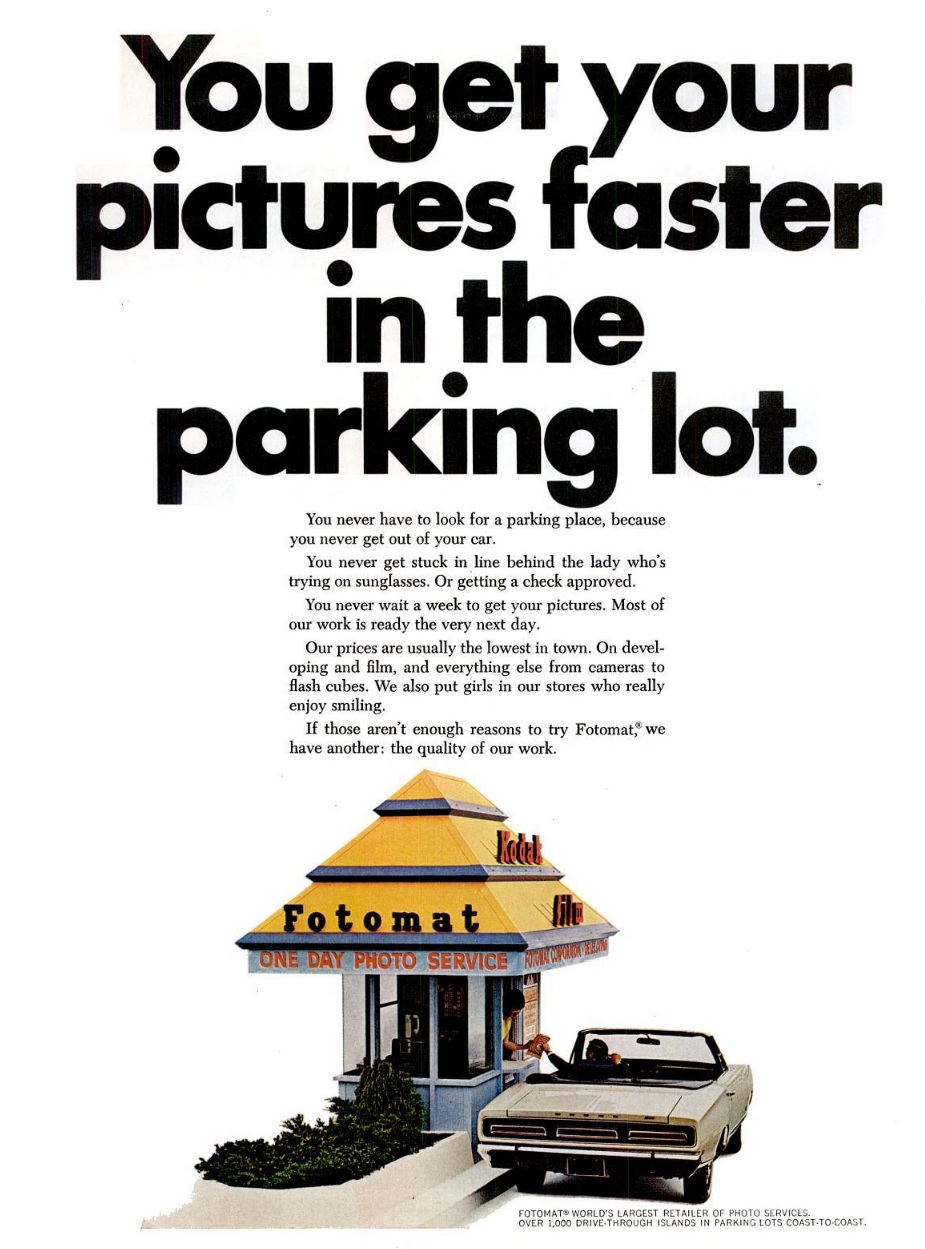

Fifty years ago today, the July 16 1971 issue of Life magazine carried this ad showing one of the most iconic structures of the 1970s, namely, the Fotomat. According to the ad, there were 1000 such structures in parking lots coast to coast.

Fifty years ago today, the July 16 1971 issue of Life magazine carried this ad showing one of the most iconic structures of the 1970s, namely, the Fotomat. According to the ad, there were 1000 such structures in parking lots coast to coast.

The first one appeared in California in 1965, the company went public in 1971, was listed on the New York Stock Exchange in 1977, and peaked at over 4000 Fotomats in about 1980.

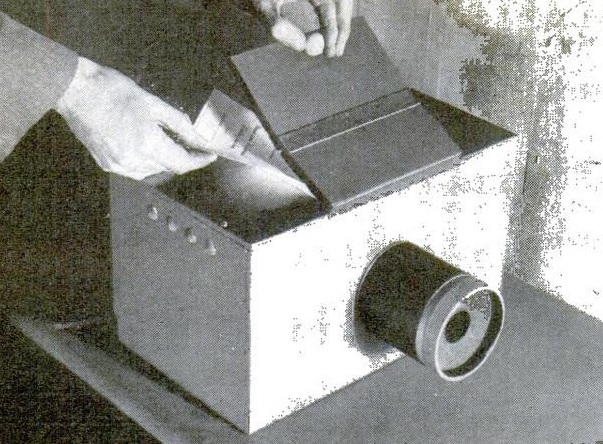

For our readers who are too young to remember, there was a time when photography required a commodity called “film” that went inside the camera. When the film was exposed to light, a latent image would form on the film. When the film was used up, it had to be removed from the camera in complete darkness, and taken somewhere to be “developed”. This process would turn the film into a “negative,” with a visible image but with the colors reversed. The negative would then essentially be photographed a second time, and turned into a “print.”

A whole industry developed around this process. Stores sold film, and many of them allowed you to drop off the film to be developed. Typically, the film was sent by the store to a distant laboratory, and you came back a few days later to pick up your prints. It wasn’t until the end of this agonizing wait that you found out whether your pictures turned out OK. You typically paid for the developing when you picked up the pictures. They would charge you to develop the roll of film, but if some of the pictures were hopeless, they wouldn’t bother making prints of those, and you would only have to pay for the ones that they printed.

There were two solutions to this agonizing delay. The first was the development of the Polaroid camera, sometimes called the Land camera in honor of its inventor, Edwin Land. (As a youngster, I mistakenly assumed that Land cameras were for use on land, and other instant cameras were better suited for use on the water.) These cameras, through a seemingly magical process, allowed you to get the finished picture after a wait of only a minute or two. We previously featured one of their early models. The Polaroid cameras and their film were, however, expensive, and the image quality was not as good as even an inexpensive traditional camera.

American business, therefore, came to the rescue, and speeded up the developing process as much as possible. The film still needed to be sent to a large lab for developing, but Fotomat was a pioneer in expediting this process as much as possible: You dropped off the film at their little building in the parking lot, without having to get out of your car. The film was sent to their lab the same day, developed overnight, and you could pick it up the very next day, again, without having to get out of your car. You could also buy film from them, as well as other photographic accessories such as flash cubes, and even low-end cameras.

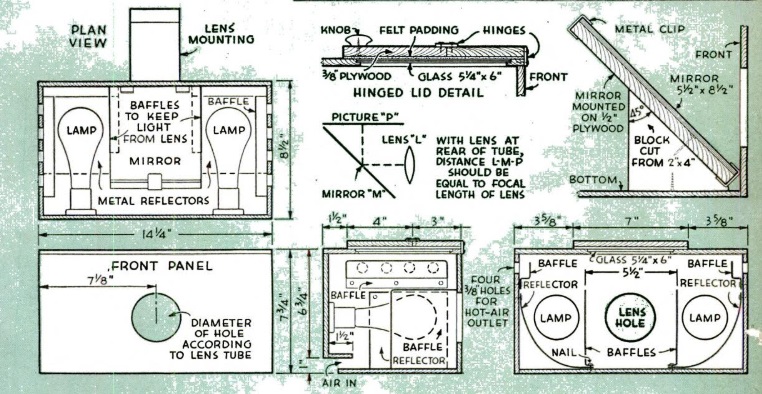

The first existential threat to Fotomat came in the 1980s with the introduction of the minilab. A minilab was a self-contained photo processing system that was small enough to put inside a retail store. No longer was it necessary to send film to a distant lab. The whole process could be done right in the store by someone with only minimal training, and it could be done while the customer waited. Fotomat allowed you to do the whole transaction without getting out of your car, but you still had to come back the next day. With the minilab, you would have to walk into the store, but you could get your pictures minutes later. Even though Fotomat “put girls in our stores who really enjoy smiling,” the chain could not compete with the faster service now offered inside a traditional store.

Of course, the final death blow to Fotomat was the digital camera, which no longer requires film or developing.

Since there were thousands of these Fotomats in supermarket parking lots around the country, many are still standing. Many of them were converted to drive-through coffee shops, although other businesses have adopted these small structures. You can see many examples at this Flickr group. You can probably see examples right in your neighborhood. Look in the parking lot of your closest strip mall, and you’ll probably find one.