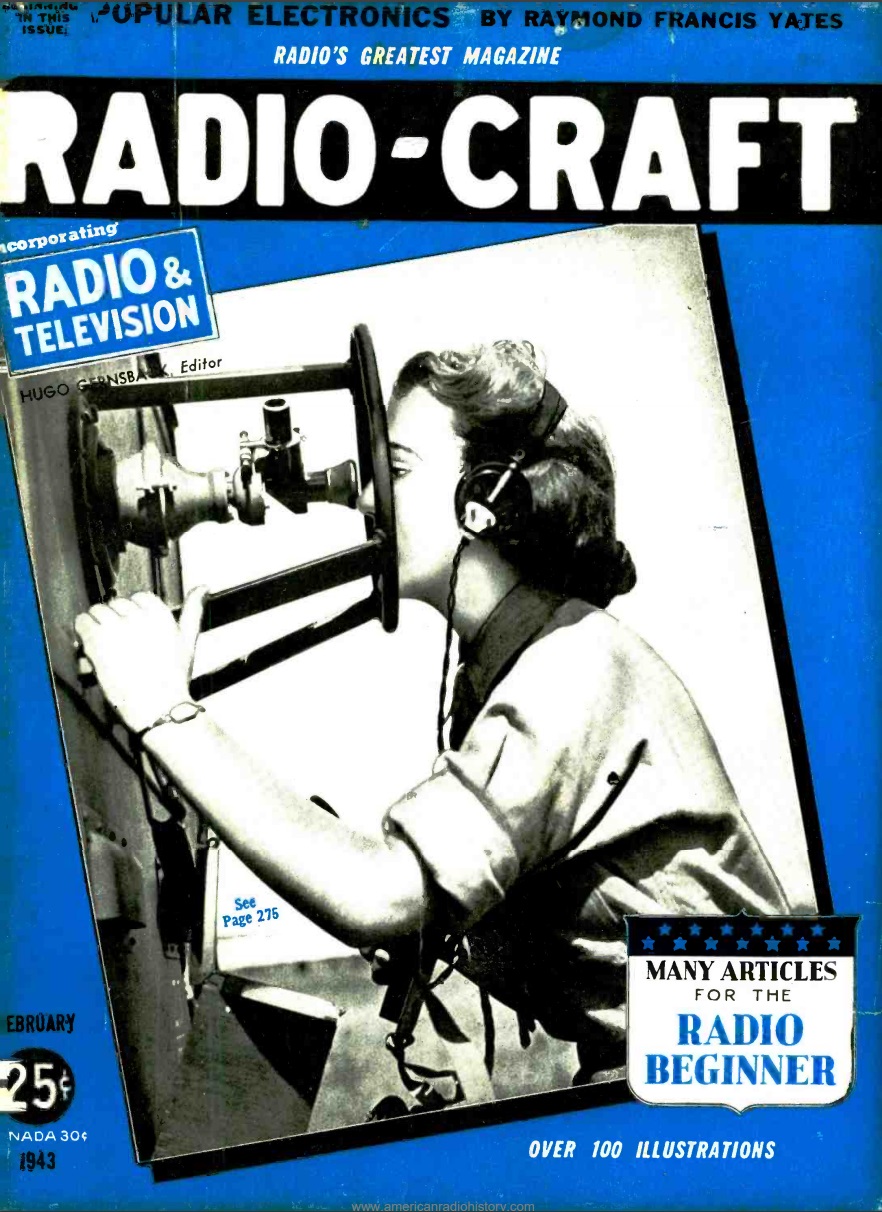

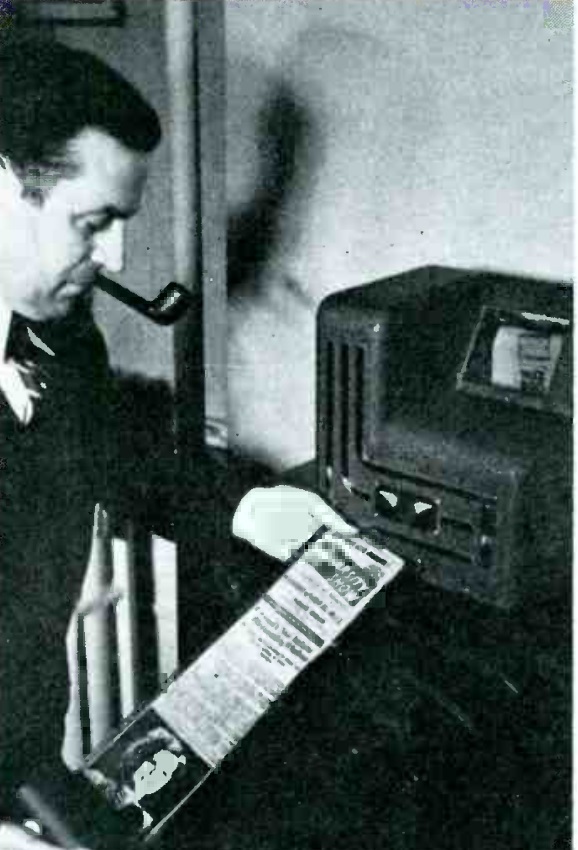

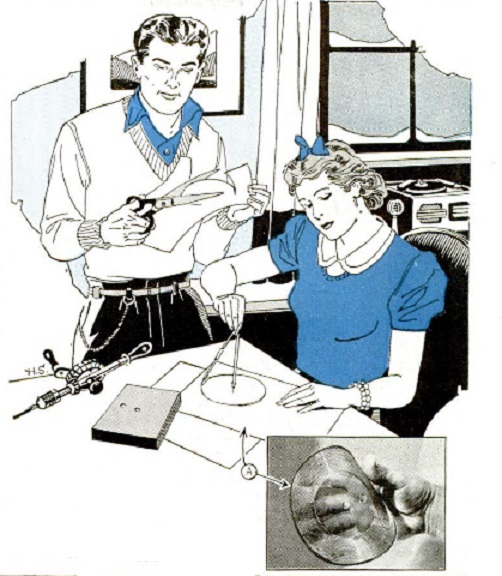

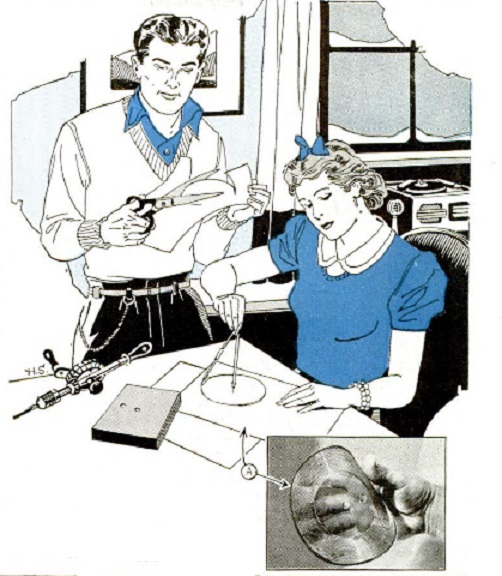

Eighty years ago, this couple owned a home recorder, visible in the background, for cutting their own 78 RPM records. It was probably a Wilcox-Gay Recordio like the one we previously featured.

Eighty years ago, this couple owned a home recorder, visible in the background, for cutting their own 78 RPM records. It was probably a Wilcox-Gay Recordio like the one we previously featured.

The problem, however, was that you had to pay for the blank discs, and you could only use them once. The least expensive blanks were six for 75 cents for the 6-1/2 inch size, up to six for $2.25 for ten-inch discs. If you wanted to do some experimenting, it could prove expensive. And there was a war going on, so it wasn’t very patriotic just to make excessive use of resources.

This couple figured out that they could make their own blank discs by using used x-ray film. You could get this by asking your friendly family doctor, and in the days before HIPAA, he would gladly give you a bunch, since they would otherwise go in the trash.

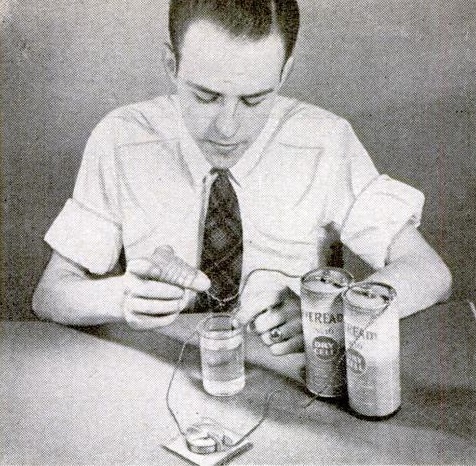

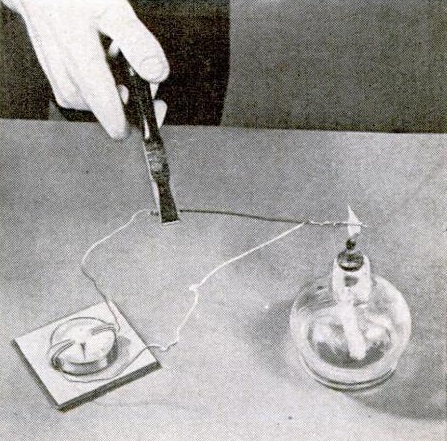

Using an old blank disc as a guide, a wooden template was made for the spindle hole as well as a locking hole that held the disc in place while being cut. These were drilled out with a hand drill. Then, a divider was used to mark the edge, and scissor and a razor blade were used to cut the form. Since these were thinner than the standard blanks, you would put them on top of a standard blank while cutting. The magazine noted that the film records could be recorded on both sides.

According to the January 1943 issue of Popular Mechanics., these homemade blanks were ideal for practicing sound effects and making practice recordings before making the final cut on commercial blanks.

I’ve never seen any other American use of this idea, but it did catch on in the Soviet Union, where “jazz on bones” (Джаз на костях) became a popular black-market method of producing records. For a ruble or two, and probably a bottle of vodka, the local physician could be talked into giving you old x-rays, which would have wound up in the trash anyway. These were used to produce bootleg copies of otherwise banned music.

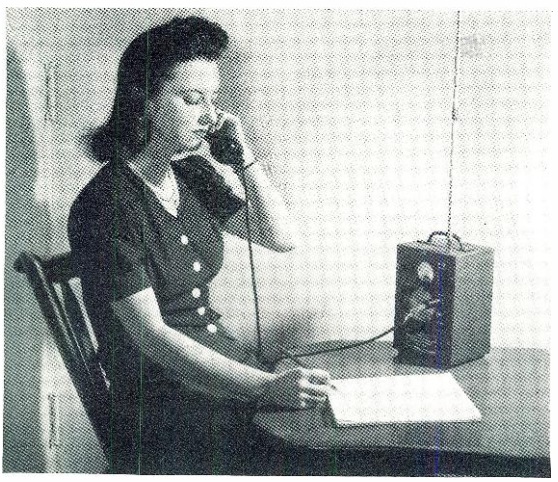

We’ve previously written about the prisoner of war broadcasts of World War 2, and eighty years ago today, the Washington Evening Star of February 16, 1943, carried this report of one such broadcast. Col. Richard G. Rogers was being held prisoner in Formosa, and recorded a message to his family in America. As often happened, listeners in America sent news to his family. There were many such letters sent in these cases, as documented in the book Letters of Compassion, but this is the first case I’ve heard of where one listener sent a phonograph record of the broadcast, undoubtedly recorded on their Recordio.

We’ve previously written about the prisoner of war broadcasts of World War 2, and eighty years ago today, the Washington Evening Star of February 16, 1943, carried this report of one such broadcast. Col. Richard G. Rogers was being held prisoner in Formosa, and recorded a message to his family in America. As often happened, listeners in America sent news to his family. There were many such letters sent in these cases, as documented in the book Letters of Compassion, but this is the first case I’ve heard of where one listener sent a phonograph record of the broadcast, undoubtedly recorded on their Recordio.