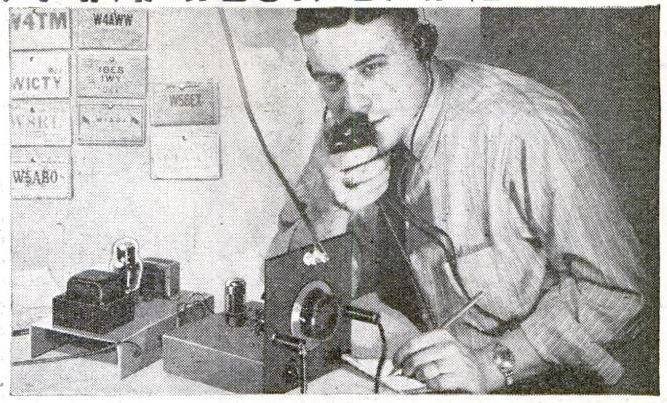

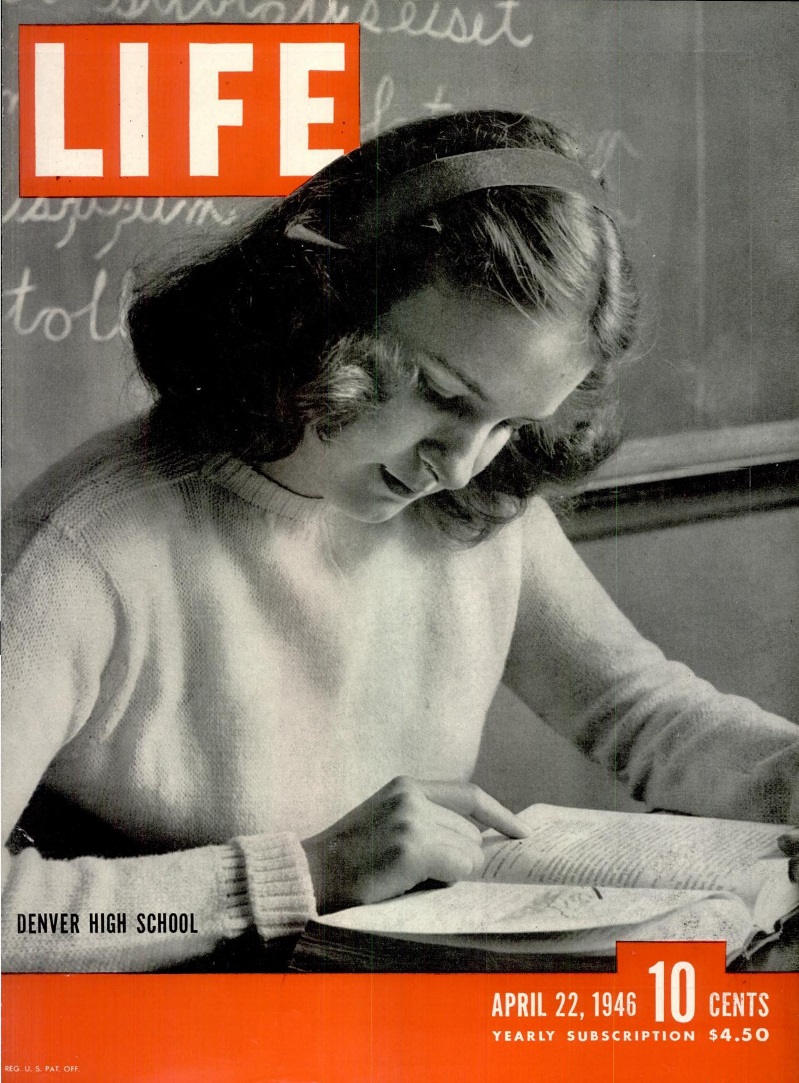

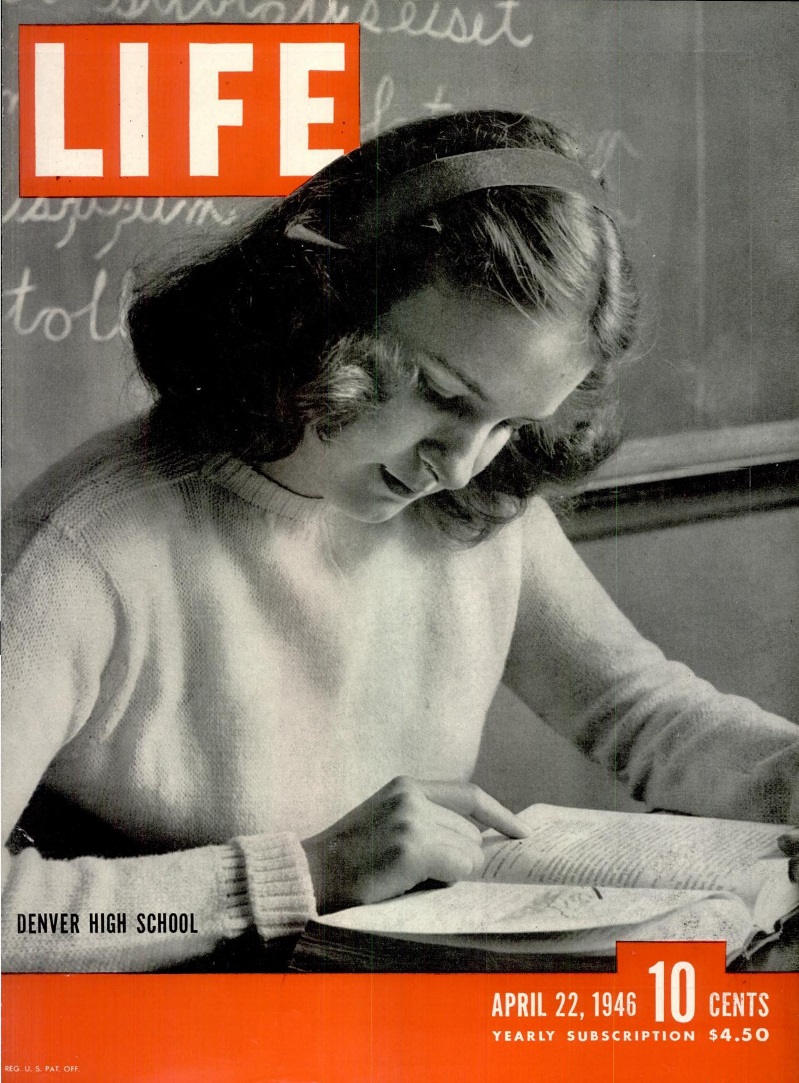

Shown on the cover of Life Magazine 75 years ago today, April 22, 1946, is Marilyn Rights, a junior at Denver East High School, in her Latin class. She would have been in seventh grade for Pearl Harbor, and most of her high school career took place during the war. The magazine profiled the school, and also took a look at the tension between two competing points of view.

Shown on the cover of Life Magazine 75 years ago today, April 22, 1946, is Marilyn Rights, a junior at Denver East High School, in her Latin class. She would have been in seventh grade for Pearl Harbor, and most of her high school career took place during the war. The magazine profiled the school, and also took a look at the tension between two competing points of view.

One view, championed by the National Education Association, called for more practical program for high school. Harvard University, on the other hand, called for more emphasis on cultural and academic subjects. The magazine’s focus was on how well the school was measuring up under the two competing plans. Harvard would be pleased to see Miss Rights’ studious attack of Latin, whereas the NEA would probably be pleased with the typing class shown here. The magazine noted that the class was one of the most popular at the school. While it was originally intended for “commercial students,” it was open to other students who learned typing in order to prepare neater homework.

One view, championed by the National Education Association, called for more practical program for high school. Harvard University, on the other hand, called for more emphasis on cultural and academic subjects. The magazine’s focus was on how well the school was measuring up under the two competing plans. Harvard would be pleased to see Miss Rights’ studious attack of Latin, whereas the NEA would probably be pleased with the typing class shown here. The magazine noted that the class was one of the most popular at the school. While it was originally intended for “commercial students,” it was open to other students who learned typing in order to prepare neater homework.

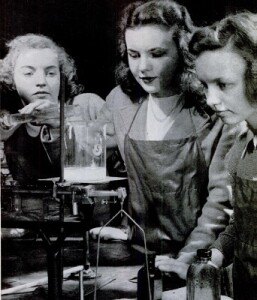

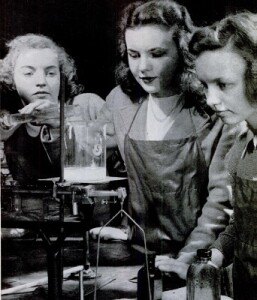

At least one of the courses, practical chemistry, allowed students to learn about cosmetics by manufacturing their own cold cream, probably with a formula such as this one involving borax.

At least one of the courses, practical chemistry, allowed students to learn about cosmetics by manufacturing their own cold cream, probably with a formula such as this one involving borax.

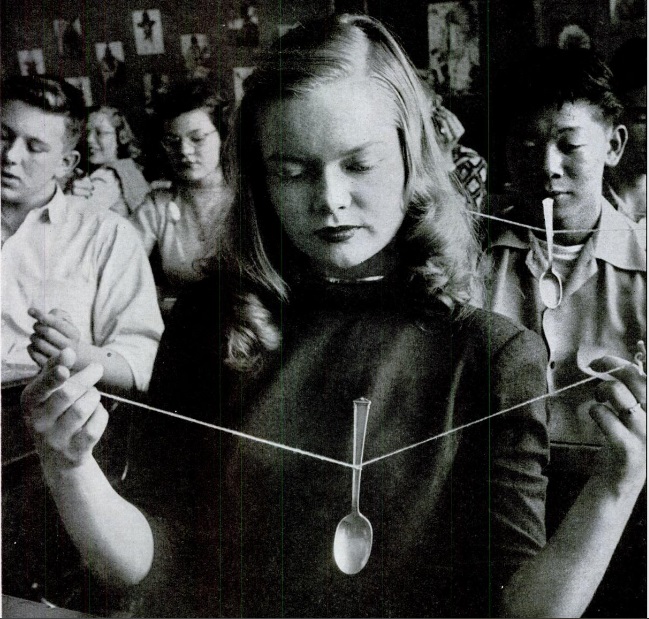

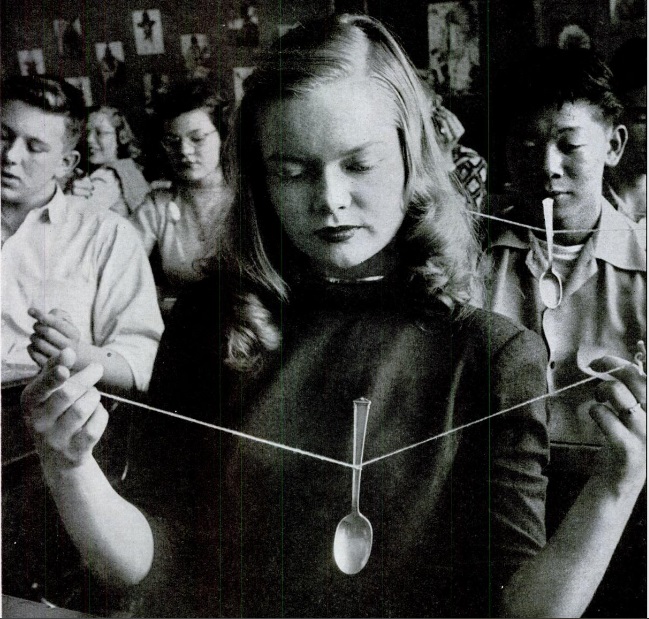

The psychology class appears to be much more interesting than the one I took in college. Here, we see the class on a field trip to see Ingrid Bergman in Spellbound, which deals with psychiatry. They discussed the film in class, and were critical of its superficial psychiatric approach. Those same students were also engrossed in the simple science experiment shown below, demonstrating how sound is transmitted to the ear. The spoon was tapped to the desk to make it vibrate, and the string held to the ear to demonstrate how the vibrations traveled through the string. In fact, elementary students looking for a simple experiment for the science fair can conduct this experiment, which you can see described at this site.

see the class on a field trip to see Ingrid Bergman in Spellbound, which deals with psychiatry. They discussed the film in class, and were critical of its superficial psychiatric approach. Those same students were also engrossed in the simple science experiment shown below, demonstrating how sound is transmitted to the ear. The spoon was tapped to the desk to make it vibrate, and the string held to the ear to demonstrate how the vibrations traveled through the string. In fact, elementary students looking for a simple experiment for the science fair can conduct this experiment, which you can see described at this site.

Another interesting activity in the psychology class is shown in the sociogram of the class below. Each student was asked to name their two best friends in the class, and these links were plotted on the chart. This revealed that the class consisted of four distinct “cliques,” which were largely independent. Girls 12 and 15 were revealed to be the most popular, with four students each identifying them as a friend. Interestingly, each was member of a separate clique. Girl 25 is identified as a “typical lonely student,” who chose students 4 and 11 as her best friends, but was herself chosen as best friend by no other student. Interestingly, though, she is the only student who links two cliques. One of her friends, 11, is a member of the clique at the left, and her other friend, 4, is a member of the lower clique.

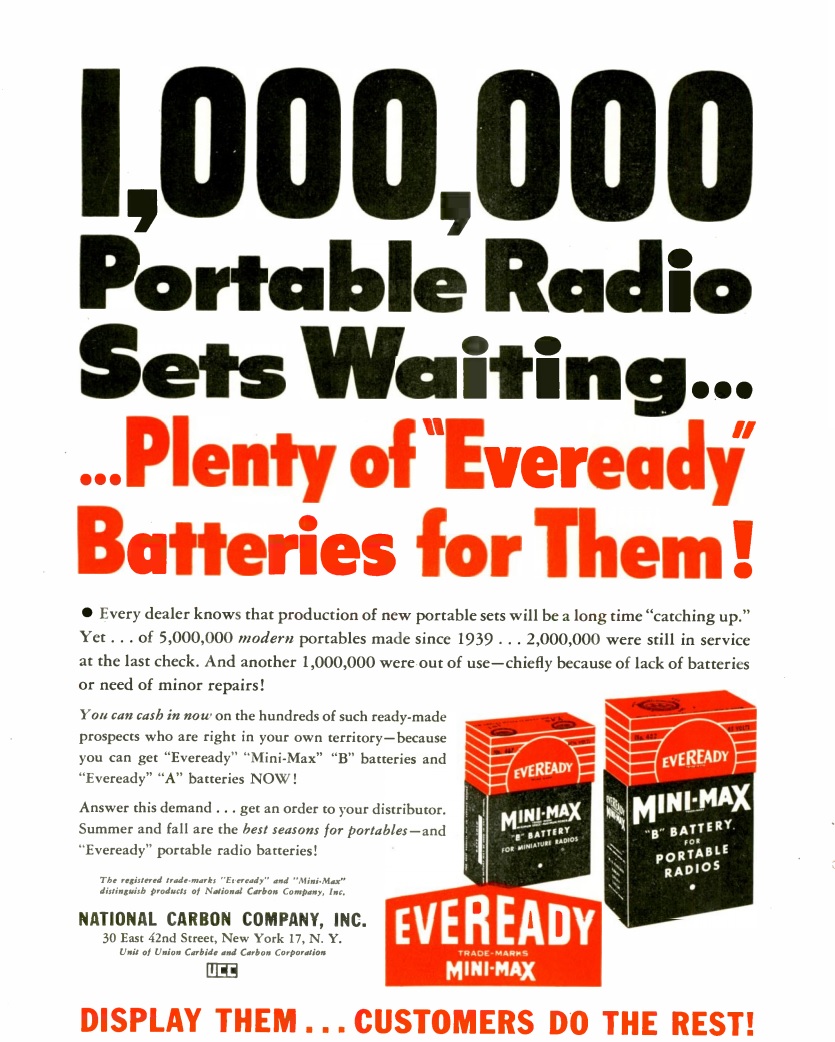

Seventy five years ago this month, the August 1946 issue of Radio Retailing carried this ad for Eveready batteries. The wartime years were ones of shortages of many consumer products, and radio batteries were difficult or impossible to find.

Seventy five years ago this month, the August 1946 issue of Radio Retailing carried this ad for Eveready batteries. The wartime years were ones of shortages of many consumer products, and radio batteries were difficult or impossible to find.