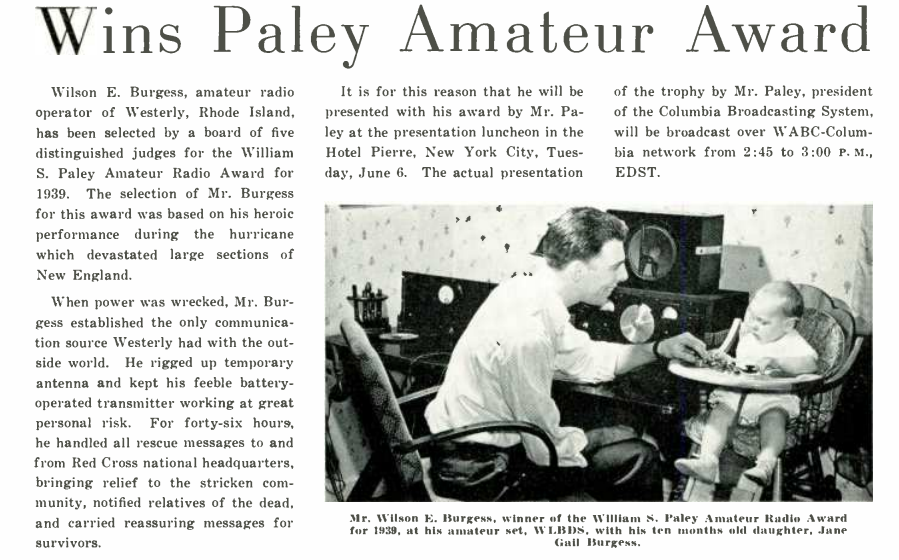

The article shown above appeared in the June 1939 issue of Rural Radio magazine, detailing an award to Wilson E. Burgess, W1BDS, for his work during the 1938 New England Hurricane. The storm was one of the deadliest to ever hit New England and Long Island, with an estimated 682 killed. It’s the strongest hurricane to hit New England in modern times, possibly eclipsed by the Great Colonial Hurricane of 1635.

The article shown above appeared in the June 1939 issue of Rural Radio magazine, detailing an award to Wilson E. Burgess, W1BDS, for his work during the 1938 New England Hurricane. The storm was one of the deadliest to ever hit New England and Long Island, with an estimated 682 killed. It’s the strongest hurricane to hit New England in modern times, possibly eclipsed by the Great Colonial Hurricane of 1635.

While this article is short on details, more can be learned from Clinton DeSoto‘s 1941 book Calling CQ.

The storm was poorly forecast, and hit Burgess’s hometown of Westerly, R.I., with little warning the afternoon of September 21, 1938. Burgess was working as the manager of the appliance department at Montgomery Ward when the storm blew out the windows of the store. Panicked people were running up and down the aisles of the store. It soon became apparent that a hurricane was in progress.

He quickly collected a quantity of batteries and started for home on foot. He struggled up the street as trees fell around him. At the police station, he met up with another amateur, George Marshall, W1KRQ. Together, the set off toward Burgess’s home with the batteries. Eventually, they were able to hitch a ride on a county truck, but it was soon blocked by trees and they again had to continue on foot.

They eventually made it, but he found that the edge of his garage that had supported his antenna had been swept away. He went out in the 65 MPH winds to put it back up, and eventually had to settle for wrapping the wire around his house.

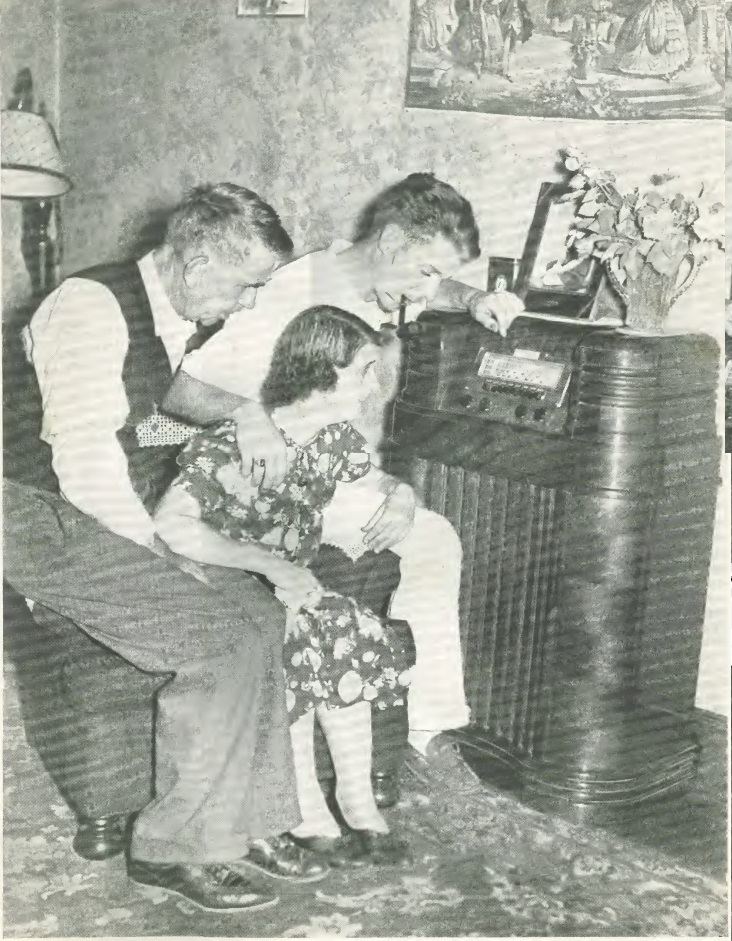

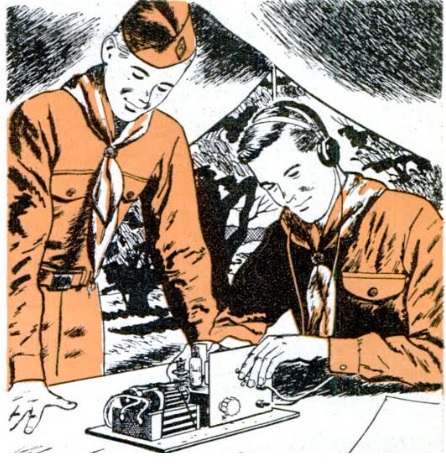

W1KRF, W1BDS, W1KRQ at the makeshift station. QST, Nov. 1938, p. 12.

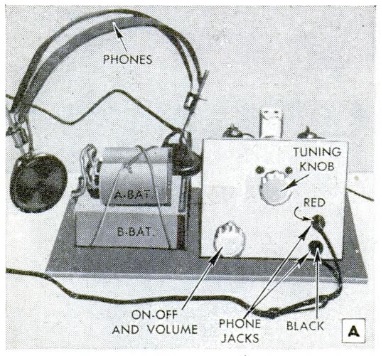

By this time, of course, the power was out, and there was no way to power Burgess’s normal 600 watt transmitter. Working by kerosene lantern, the two men worked for two hours building a one-tube transmitter to use with the batteries carried from the store. DeSoto reports that the windows had been blown out by this time, and daughter Jane Gail Burgess, shown in the photo above, then three months old, was crying in terror.

Finally, they had the transmitter and a makeshift receiver ready, and Burgess started putting out a QRR–the then-distress call. Unfortunately, nobody really knew that an emergency was in progress, and their weak signal simply wasn’t heard over the interference of a normal busy ham band. They moved their CW signal up to the phone band, reasoning that the CW signal would stand out there. The trick worked, and soon W2CQD in New Jersey answered the call, with W1SZ in Connecticut (QST managing editor) later taking over. For the next five days, the Connecticut station maintained contact.

Neighbors eventually got word to the local Red Cross that radio contact had been made, and the house soon became a center for relief activity. The first official message was to Red Cross headquarters in Washington, but that message was not accepted, since it was signed merely “Westerly Red Cross.” Eventually, the name of the local chairman was added, and the message was accepted.

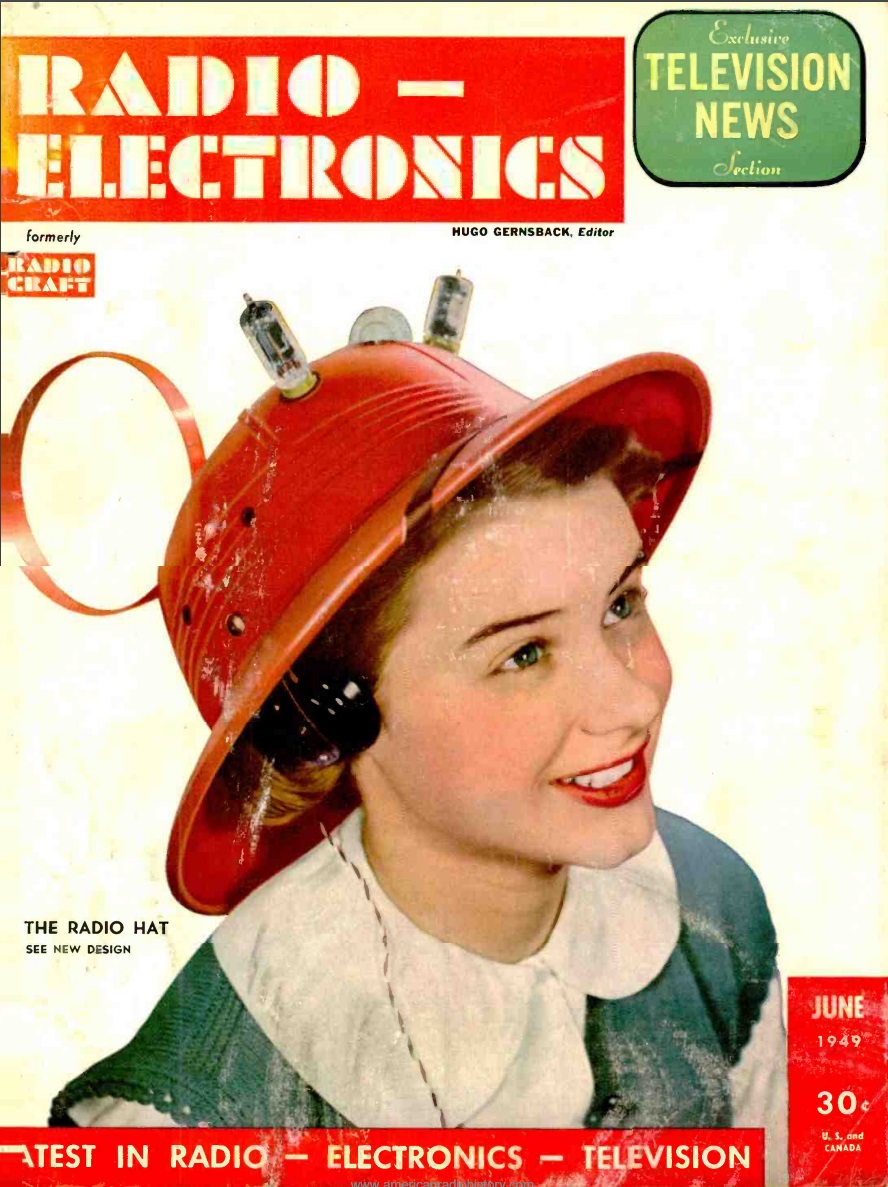

Eighty years ago this month, the young woman shown here was pulling in some musical entertainment on her way to the beach, courtesy of her Majestic model 130 portable radio. The “camera style” set, billed as the world’s smallest portable, featured a superheterodyne circuit, with a 3-tube lineup consisting of 1A7GT, 1N5GT, and 1D8GT, powered by a 60 volt B battery and a 1.5 volt battery to light the filaments.

Eighty years ago this month, the young woman shown here was pulling in some musical entertainment on her way to the beach, courtesy of her Majestic model 130 portable radio. The “camera style” set, billed as the world’s smallest portable, featured a superheterodyne circuit, with a 3-tube lineup consisting of 1A7GT, 1N5GT, and 1D8GT, powered by a 60 volt B battery and a 1.5 volt battery to light the filaments.