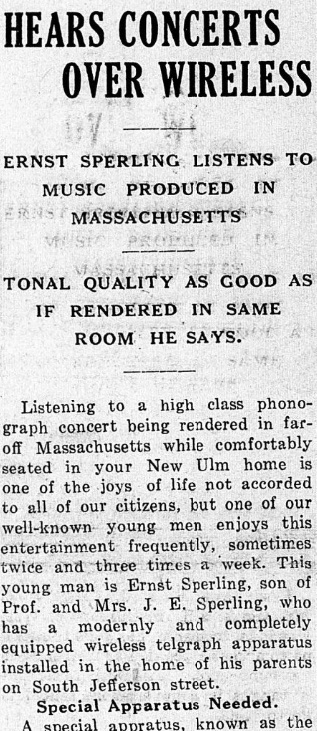

This article appeared a hundred years ago today, in the January 26, 1921 issue of the New Ulm (MN) Review.

This article appeared a hundred years ago today, in the January 26, 1921 issue of the New Ulm (MN) Review.

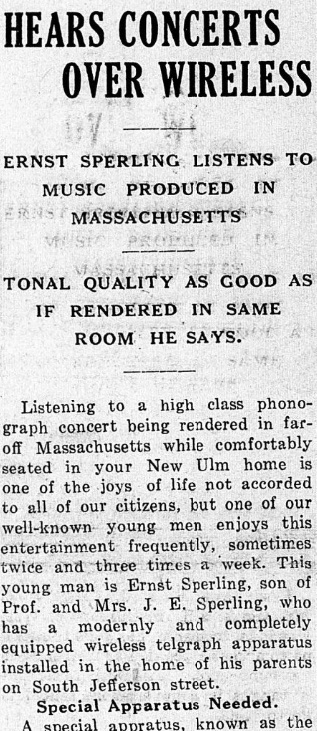

HEARS CONCERTS OVER WIRELESS

ERNST SPERLING LISTENS TO MUSIC PRODUCED IN MASSACHUSSETS

TONAL QUALITY AS GOOD AS IF RENDERED IN SAME ROOM HE SAYS

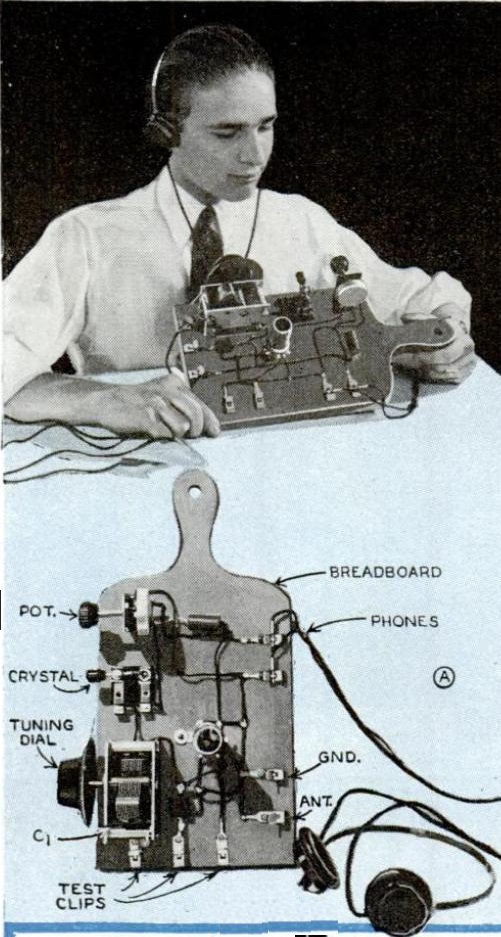

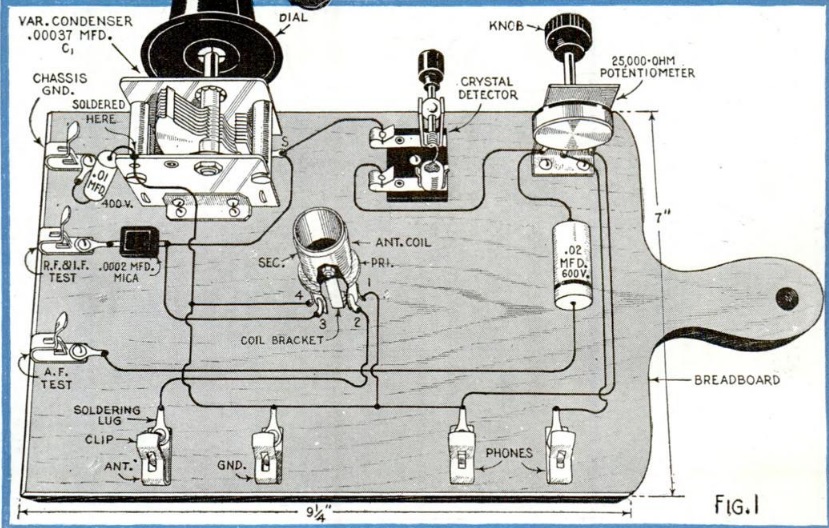

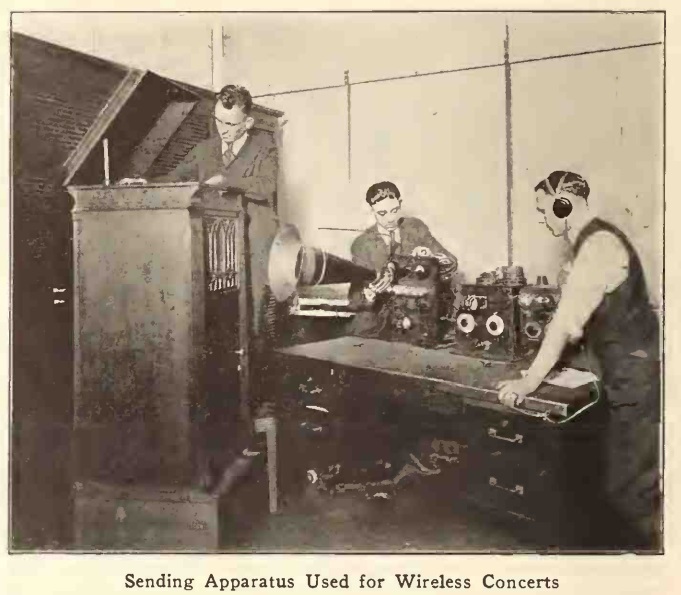

Listening to a high class phonograph concert being rendered in far off Massachusetts while comfortably seated your New Ulm home is one of the joys of life not accorded to all of our citizens, but one of our well-known young men enjoys this entertainment frequently, sometimes twice and three times a week. This young man is Ernst Sperling, son of Prof. and Mrs. J. E. Sperling, who has a modernly a completely equipped wireless telegraph apparatus installed the home of his parents on [21] South Jefferson street.

Special Apparatus Needed.

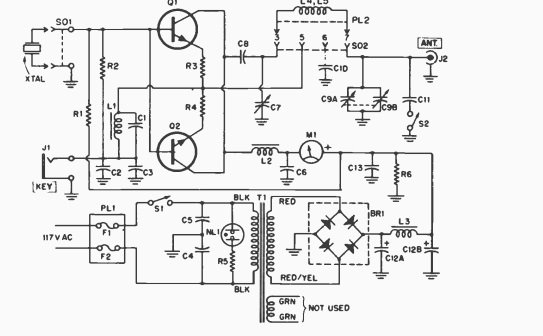

A special apparatus, known as the audion receiving set, is necessary to receive music by wireless. This apparatus is more sensitive and of a better grade than the regular wireless receiving instrument. There is very little electrical energy used in transmitting music waves by wireless, so that the detector must be unusually sensitive, or the other tones will not be clear. Another important factor in the transmission of music via wireless is the prevailing weather conditions. If the air is clear and quiet, with no perceptible wind, the music is much more audible and there is no rising or falling of the tone During a wind that is strong enough to sway the antenna the music sounds as if it were being played on a phonograph, the modultor of which is being changed constantly.

News Every Night.

Mr. Sperling spends a considerable part of his spare time evenings at his wireless instrument and receives many messages containing accounts of important happenings not only in this country but abroad also. One of the principal sources of this in formation is the big wireless station on Arlington Heights, near Washington, D. C., from which such messages are sent out every evening. He also receives messages from commercial stations every section of the United States, the most distant one being located in Alaska.

“Connect” With Europe.

Mr Sperling is at present working on a large receiving set, which, when completed, will enable him to get wireless messages direct from Europe, thus enlarging the scope of his wire less work. Quite a number of interested New Ulmites have visited the Sperling home to view the young man’s wireless apparatus and have him explain its workings.

Later in the year, the newspaper’s June 1, 1921, edition reported that young Mr. Sperling had agreed to supply farm market reports to the telephone company, which made them available to local farmers.

Sperling is listed in the 1922 callbook as being licensed as 9BBF (with his name spelled Ernest). His father, Prof. J.E. Sperling of Dr. Martin Luther College is listed in this yearbook as a Pastor Emeritus of the Joint Wisconsin Synod of the Lutheran Church.

In the 1937 callbook, Ernest is listed as one of two licensees, along with one Victor H. Schleuder, as licensee of W9BKX of 313 S. State St., New Ulm. He is listed in the 1940 census as living at 21 South Franklin.

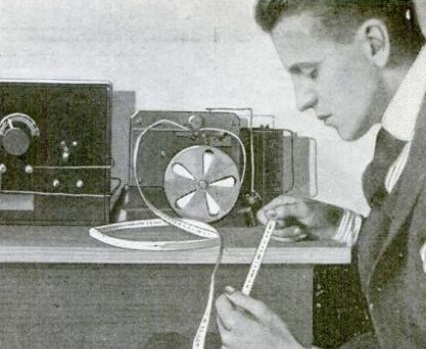

75 years ago, this young man discovered the secret for meeting girls. That, of course, was explaining to them how transformers worked. This young woman is obviously mesmerized by his explanation.

75 years ago, this young man discovered the secret for meeting girls. That, of course, was explaining to them how transformers worked. This young woman is obviously mesmerized by his explanation.