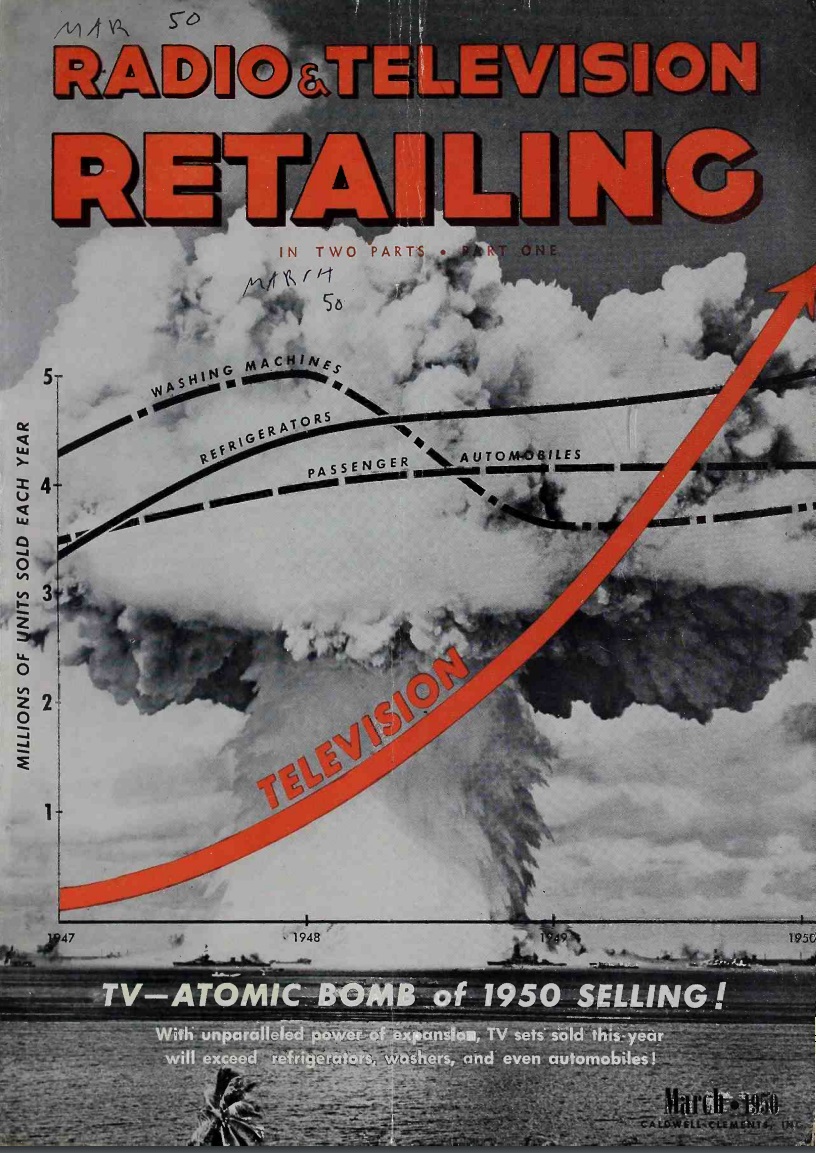

Seventy-five years ago this month, the cover of the March 1950 issue of Radio Retailing cheerfully predicted that television sales would be the atomic bomb of the year! TV sales were set to outpace refrigerators, washers, and even automobiles.

Seventy-five years ago this month, the cover of the March 1950 issue of Radio Retailing cheerfully predicted that television sales would be the atomic bomb of the year! TV sales were set to outpace refrigerators, washers, and even automobiles.

Seventy-five years ago this month, the cover of the March 1950 issue of Radio Retailing cheerfully predicted that television sales would be the atomic bomb of the year! TV sales were set to outpace refrigerators, washers, and even automobiles.

Seventy-five years ago this month, the cover of the March 1950 issue of Radio Retailing cheerfully predicted that television sales would be the atomic bomb of the year! TV sales were set to outpace refrigerators, washers, and even automobiles.

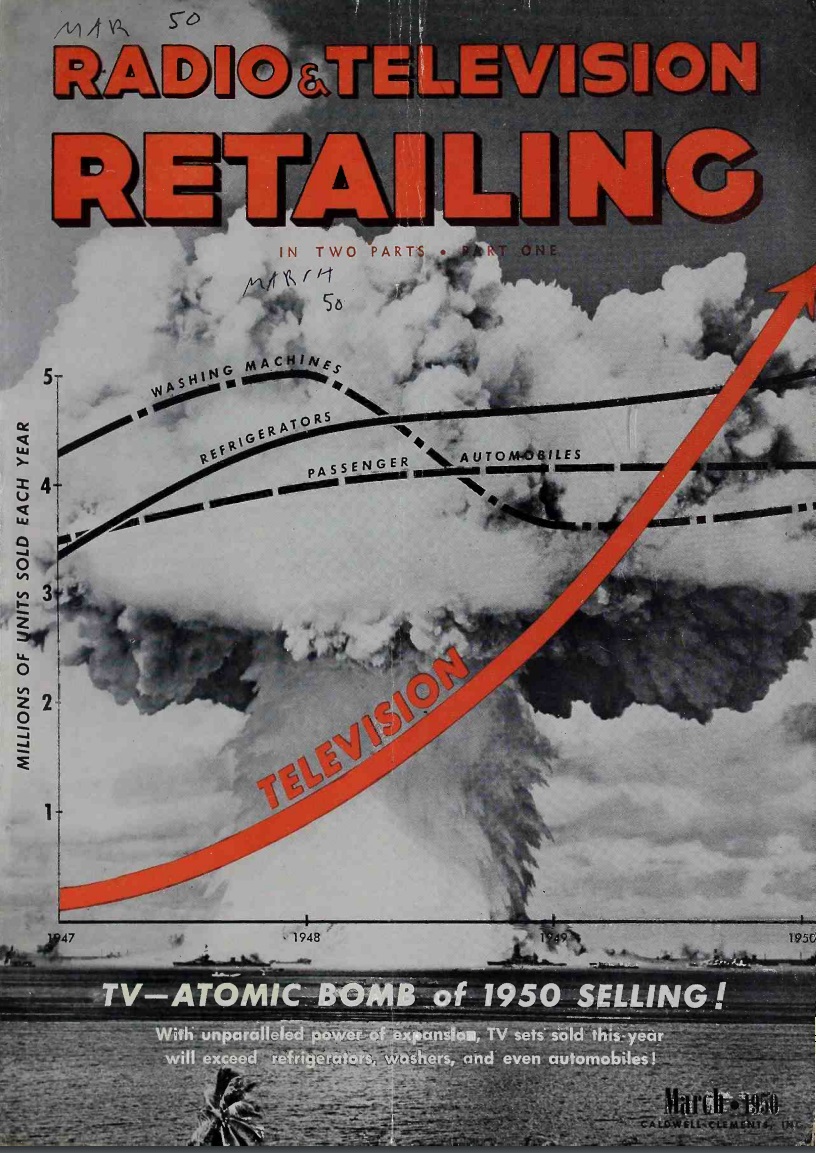

Seventy-five years ago, the millionth clock radio was getting ready to roll off the General Electric assembly lines, and GE planned to celebrate. They were conducting a contest to give the radio to a lucky winner, who would also travel to New York to meet Fred Waring and the Pennsylvanians.

Seventy-five years ago, the millionth clock radio was getting ready to roll off the General Electric assembly lines, and GE planned to celebrate. They were conducting a contest to give the radio to a lucky winner, who would also travel to New York to meet Fred Waring and the Pennsylvanians.

The set, a model 506, was billed as the world’s most useful radio. It would lull you to sleep and then waken you to music or buzzer. It could even control a light to waken the hard of hearing. And in the kitchen, it could be used to control a coffee pot or other appliance. And, of course, it could remind you of important appointments.

This ad appeared in Life Magazine, March 13, 1950.

Sixty years ago this month, the March 1965 issue of Electronics Illustrated devoted much of the issue to a new kind of electronic component, the integrated circuit. In particular, it included some projects making use of the Motorola MC356G IC. The device, measuring only 5/16″ in diameter, packed in a full six transistors, along with five resistors. It could be had for only $3.55 plus postage.

Sixty years ago this month, the March 1965 issue of Electronics Illustrated devoted much of the issue to a new kind of electronic component, the integrated circuit. In particular, it included some projects making use of the Motorola MC356G IC. The device, measuring only 5/16″ in diameter, packed in a full six transistors, along with five resistors. It could be had for only $3.55 plus postage.

The IC was designed for logic applications, so putting those transistors to use in a radio posed some challenges, since they were packed so close together physically. But with some trial and error, the magazine settled on the circuit shown below, which had good selectivity, sensitivity, and audio output.

The circuit used four of the six transistors. Components inside the IC are shown in black in the schematic, with added components in red.

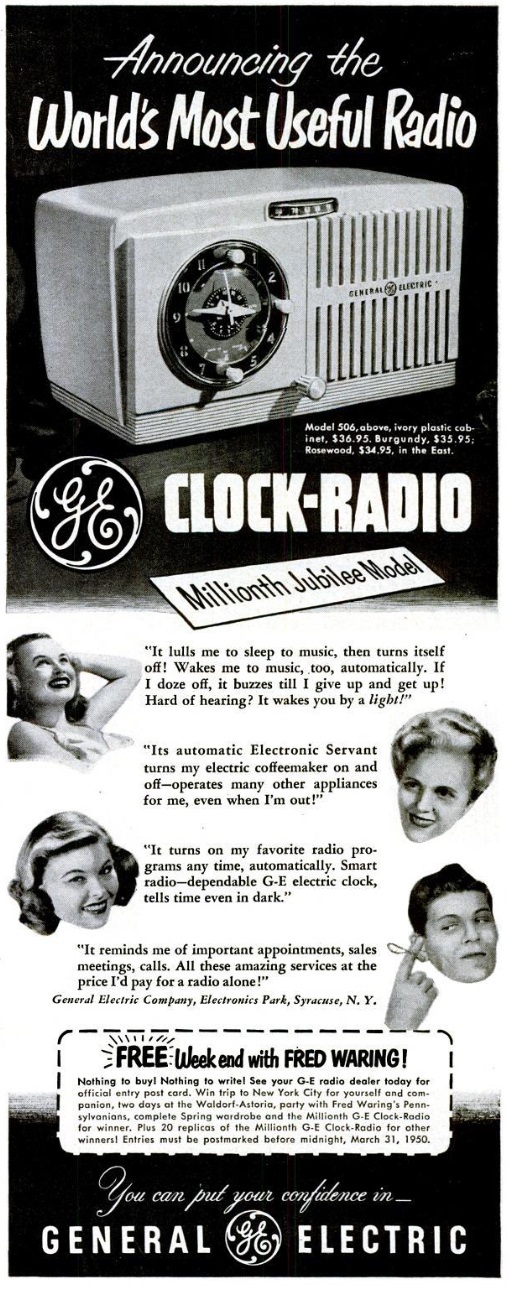

The excitement is palpable in this image from the cover of the March 1955 issue of Practical Wireless. It looks like they’re simply listening to a record on their radiogram (what we would call a radio-phono on this side of the Pond). But one of them actually built the set according to plans in the magazine.

The excitement is palpable in this image from the cover of the March 1955 issue of Practical Wireless. It looks like they’re simply listening to a record on their radiogram (what we would call a radio-phono on this side of the Pond). But one of them actually built the set according to plans in the magazine.

The set was said to be a selective and sensitive station getter, and had a tolerably high standard of reproduction for both the wireless and the gramophone. The March issue started the construction plans for the eight-tube set, to be continued in the April issue.

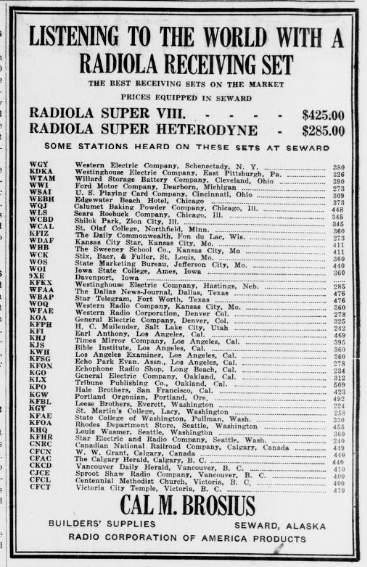

This ad for dealer Cal M. Brosius appeared a hundred years ago today in the March 9, 1925, issue of the Seward (AK) Daily Gateway. There were no broadcast stations in Alaska, so a crystal set probably wouldn’t do you much good. But if you had a superheterodyne, there would be a lot to listen to at night. This dealer included a list of stations that had been received in Seward on the Radiola Super VIII or Super Heterodyne. They included stations on the east coast, as well as stations in western Canada and the U.S. west coast.

This ad for dealer Cal M. Brosius appeared a hundred years ago today in the March 9, 1925, issue of the Seward (AK) Daily Gateway. There were no broadcast stations in Alaska, so a crystal set probably wouldn’t do you much good. But if you had a superheterodyne, there would be a lot to listen to at night. This dealer included a list of stations that had been received in Seward on the Radiola Super VIII or Super Heterodyne. They included stations on the east coast, as well as stations in western Canada and the U.S. west coast.

But it wouldn’t be cheap. The Super Heterodyne would set you back $285, and the Super VIII would be $425. When adjusted for inflation, that works out to $5233 and $7804.

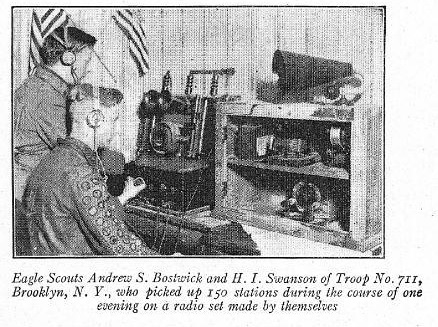

One hundred years ago this month, the March 1925 issue of Boys’ Life showed Eagle Scouts Andrew S. Bostwick and H.I. Swanson, both of Troop 711, Brooklyn, at the controls of the radio they had built. The magazine reported that they picked up 150 stations during the course of one evening.

One hundred years ago this month, the March 1925 issue of Boys’ Life showed Eagle Scouts Andrew S. Bostwick and H.I. Swanson, both of Troop 711, Brooklyn, at the controls of the radio they had built. The magazine reported that they picked up 150 stations during the course of one evening.

Perhaps the duo inspired some scouts to build the two-tube receiver described in the same issue of the magazine:

The young man in this drawing is now a senior citizen, but in 1965, he was taking part in the school science fair, using a project shown in the Winter 1965 issue of Elementary Electronics. He was communicating with a light beam, with a rudimentary setup consisting of two audio amplifiers. The output of one of them was hooked directly to a light bulb (in series with a 3 volt battery), and the input of the other one was hooked to a photocell.

The young man in this drawing is now a senior citizen, but in 1965, he was taking part in the school science fair, using a project shown in the Winter 1965 issue of Elementary Electronics. He was communicating with a light beam, with a rudimentary setup consisting of two audio amplifiers. The output of one of them was hooked directly to a light bulb (in series with a 3 volt battery), and the input of the other one was hooked to a photocell.

According to the article, this unit was good for demonstration purposes only, and was only capable of a couple of feet. I’m surprised that they are so conservative in their estimate, since I made virtually the same setup when I was a kid, and it traversed the length of the house without much difficulty.

The only difference in my version was the addition of a transformer to the output of the first amplifier. The primary was hooked to the amp, and the secondary was wired in series with the battery. I used a flashlight, and just sandwiched two pieces of foil, insulated by cardboard, between the lamp and the battery terminal. I suspect my use of a flashlight, complete with its parabolic reflector, was probably an important factor in my success.

Eighty-five years ago, this no-nonsense outdoorswoman is enjoying a hike, but when she stops to rest, she can listen to a favorite program on this combination cane/seat/radio described in the March 1940 issue of Popular Science.

Eighty-five years ago, this no-nonsense outdoorswoman is enjoying a hike, but when she stops to rest, she can listen to a favorite program on this combination cane/seat/radio described in the March 1940 issue of Popular Science.

One HY115 tube served as a regenerative detector, with a second serving as AF amplifier. A final HY125 audio stage powered the headphones. The cane itself could serve as an antenna, or a convenient fence wire could be used.

As with everything, cane-seats can still be found on Amazon. The exact instructions for mounting a radio will differ, but we’re confident that our readers can figure it out.

Some links on this page are affiliate links, meaning that this site earns a small commission if you make a purchase after using the link.

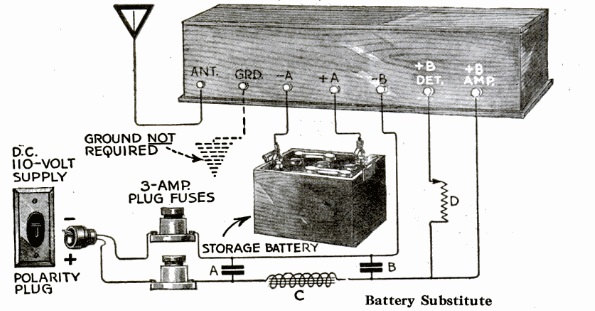

If you were one of the growing number of Americans who owned a radio 100 years ago, the cost of batteries would soon become a concern, and you would be thinking of ways to run the radio from your lighting current.

If you were one of the growing number of Americans who owned a radio 100 years ago, the cost of batteries would soon become a concern, and you would be thinking of ways to run the radio from your lighting current.

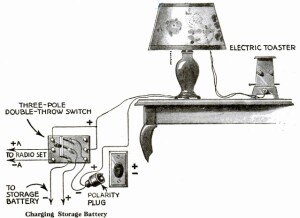

In many large cities, the power company supplied 110 volts direct current, and if that was your situation, the March 1925 issue of Popular Science showed you how to power the radio. Even though the power was DC, the generators down at the power plant generated a lot of ripple, and if you just ran the radio straight from the line, the result would be a loud high pitched whine. So the filtering arrangement above could be used.

For the filaments, since you already had a battery, you could just use that, but then recharge it with 110 volts DC, as shown here. To drop the voltage, you would start with a 60 watt lightbulb in series. But to finish the job, you would want to lower the current, which meant putting the toaster in series.

For the filaments, since you already had a battery, you could just use that, but then recharge it with 110 volts DC, as shown here. To drop the voltage, you would start with a 60 watt lightbulb in series. But to finish the job, you would want to lower the current, which meant putting the toaster in series.

If you weren’t sure about the polarity, you could run the simple test below:

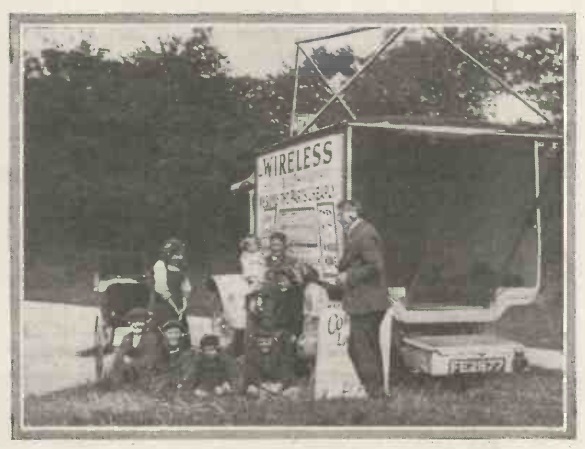

One hundred years ago, an entrepreneurial radio dealer in Horsham, England, noticed that interest in wireless was lagging in nearby villages. He took it upon himself, therefore, to equip a motor van with a complete receiving set an hit the road. He paid periodical visits to enable the inhabitants to enjoy a wireless concert, and to bring to their attention the fact that his firm could sell them a set of their own.

One hundred years ago, an entrepreneurial radio dealer in Horsham, England, noticed that interest in wireless was lagging in nearby villages. He took it upon himself, therefore, to equip a motor van with a complete receiving set an hit the road. He paid periodical visits to enable the inhabitants to enjoy a wireless concert, and to bring to their attention the fact that his firm could sell them a set of their own.

In this picture, in the February 1925 issue of Wireless magazine, and it is noted that great pleasure is written upon the faces of the children listening here.