A hundred years ago, American amateur radio operators were off the air for the duration of the war. All stations, both receiving and transmitting, had to be dismantled, and antennas lowered to the ground. But the July 1917 issue of Electrical Experimenter detailed the activities of 24 year old Archie Banks of rural Delmar, Iowa. Banks lived on a farm about a mile out of town, and when he was sixteen, he developed an interest in electricity. He had the house wired with electric lights powered by batteries, and within two years, he was dabbling in wireless. He reported that his first set didn’t work well, and he could only communicate the one mile to Delmar.

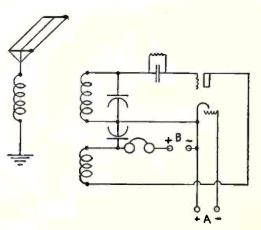

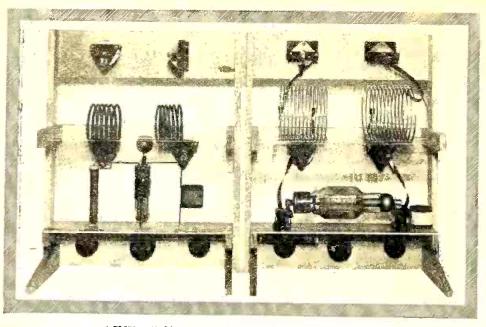

But his second station was considerably more successful. He was licensed as 9AGD, and among other things was able to reliably copy the twice daily news and weather reports sent by the stations at the Illinois State Agricultural College in Springfield, and the Iowa State Agricultural College at Ames.

Rather than keep these important bulletins to himself, Banks took it upon himself to share the information with neighbors. Initially, he shared the information with anyone who desired to phone him, and the service was popular. Area farmers had access to immediate weather reports, rather than having to wait for the daily nespaper to be delivered by the R.F.D. carrier.

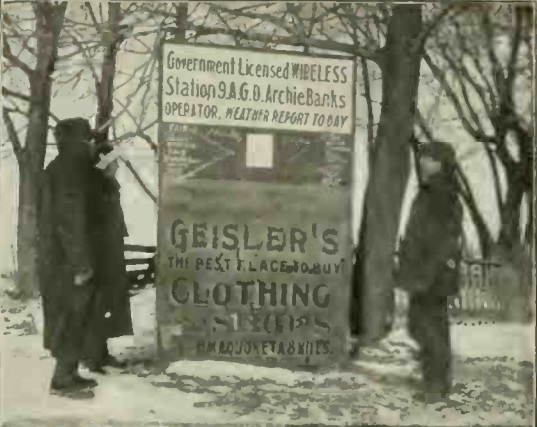

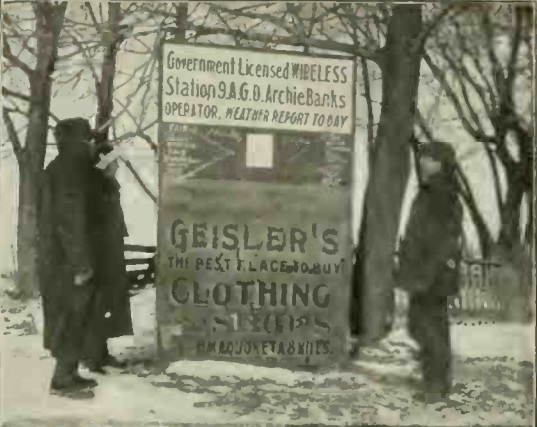

But Banks decided to carry it a step further, as shown by the sign here. In addition to his labor on the family farm, Banks had a side business consisting of about a hundred hives which he used to raise honey. The honey was advertised by a roadside sign. He added this sign, encouraging passers by to stop and read the news and weather reports. Initially, the sign was placed as a public service. But Banks soon noticed that those stopping to read the weather would be in a good position to buy some honey.

Banks had his beekeeping-wireless enterprise in operation as early as 1913. In that year, he had a paper read at the state bee convention, published in the Report of the State Bee Inspector, an essay entitled, “The Art of Selling Honey From a Producer’s and Retailer’s Point of View.” This paper reveals that the wireless was but one advertising mechanism he employed. He recommended advertising which included a few recipes. “This will make the housewife anxious to try them out just the same as one is to try a new car.” He recommended giving out samples, since they “create an appetite for more and the neighbor or friend will probably purchase a case or more the next time he sees you.”

His main sign (not shown in the Electrical Experimenter article” was eight feet by two feet and “hung across the road,” which was a main highway. It read, in large red letters, “Eat Honey,” with the phrase “for sale here by the section or wagon load” in large black letters. He states that he also had “a large signboard on which is printed the weather report which I receive daily by wireless. Passerby stopping to read this report get a view of the honey sign also–thus killing two birds with one stone.”

Banks is also described in an article in this 1917 issue of The Country Gentleman.

According to this link, Banks was born in 1892, the son of B.D. Banks and Hannah E. Banks. According to this 2016 obituary of his son Harlan Banks, he later married Edna Bowman and had multiple children. At some point, he moved to California, since the son’s obituary shows him graduating from high school in Santa Barbara.

According to this site, in 1925, Banks was one of five hams in Santa Barbara when an earthquake struck the town on June 29, 1925. The city was completely cut off from the outside world, prompting the hams to patch together a CW station to send out an SOS. Help was summoned when an operator aboard a Standard Oil Tanker heard the SoS and summoned help. This photo, appearing in a Russian language book, shows Banks operating from Santa Barbara after the earthquake.

According to this site, in 1925, Banks was one of five hams in Santa Barbara when an earthquake struck the town on June 29, 1925. The city was completely cut off from the outside world, prompting the hams to patch together a CW station to send out an SOS. Help was summoned when an operator aboard a Standard Oil Tanker heard the SoS and summoned help. This photo, appearing in a Russian language book, shows Banks operating from Santa Barbara after the earthquake.

According to the Social Security Death Index, Banks died in October 1984 in Santa Barbara. According to his gravestone, he served in the U.S. Navy both World War I and World War II.

Banks is listed as 9AGD in the 1916 callbook with an address of R.F.D. 2, Delmar, Iowa. He doesn’t appear to have a listing, either in California or Iowa, in the 1922 call book.

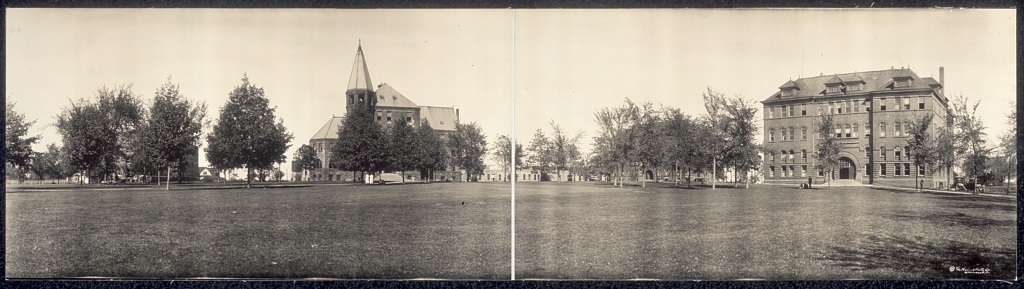

Interestingly, I think I found the location of Banks’ 1917 honey sign, which would be this Google street view. According to the Electrical Experimenter article, Banks’ station was about one mile from Delmar and eight miles from Maquoketa. This farm house is about that distance from the two towns, and seems to match the house shown in the article, assuming the magazine photo below was taken from the rear of the house. The location is on Iowa Highway 136, just west of US Highway 61.

Interestingly, I think I found the location of Banks’ 1917 honey sign, which would be this Google street view. According to the Electrical Experimenter article, Banks’ station was about one mile from Delmar and eight miles from Maquoketa. This farm house is about that distance from the two towns, and seems to match the house shown in the article, assuming the magazine photo below was taken from the rear of the house. The location is on Iowa Highway 136, just west of US Highway 61.

Shown here on the cover of the February 1958 issue of Radio & TV News is Dorothy Hicks, K0BRZ, of Omaha, Nebraska, at the controls of the demonstration ham shack of World Radio Laboratories (WRL) in neighboring Council Bluffs, Iowa. The store maintained the station to showcase available products, both its own and those of other manufacturers, which were rotated through the station on a regular basis. The station was made available to hams passing through who might need to maintain a schedule, as well as to new novices.

Shown here on the cover of the February 1958 issue of Radio & TV News is Dorothy Hicks, K0BRZ, of Omaha, Nebraska, at the controls of the demonstration ham shack of World Radio Laboratories (WRL) in neighboring Council Bluffs, Iowa. The store maintained the station to showcase available products, both its own and those of other manufacturers, which were rotated through the station on a regular basis. The station was made available to hams passing through who might need to maintain a schedule, as well as to new novices.