Today marks the 70th anniversary of the deadliest industrial accident in U.S. history, the Texas City disaster of April 16, 1947, which started as a fire aboard the French-registered vessel SS Grandcamp docked at Texas City, Texas, with 2200 tons of ammonium nitrate. The disaster killed at least 581 people, including all but one member of the Texas City fire department.

Smoke was spotted in the cargo hold of the Grandcamp at about 8:00 AM. The captain ordered his crew to steam the hold, which probably made matters worse by converting the ammonium nitrate to nitrous oxide.

Spectators gathered, believing that they were a safe distance away. The sealed hold began to bulge, and water splashing against the hull began to boil.

The cargo detonated at 9:12 AM, with a blast leveling over a thousand buildings on land and destroyed the Monsanto chemical plan and ignited refinery and chemical tanks on the waterfront. Bails of twine from the cargo were set afire and hurled around the city. People in Galveston, 10 miles away, were forced to their knees, and the shock wave was felt as far as 250 miles away.

The ironically named SS High Flyer was docked nearby, and the blast set fire to that ship’s cargo of ammounium nitrate. Fifteen hours later, that ship exploded.

As might be expected, the blast destroyed much of the city’s communication infrastructure, and amateur radio operators quickly responded to fill the gap. Many of these stories are detailed in the July 1947 issue of QST (pages 38-40).

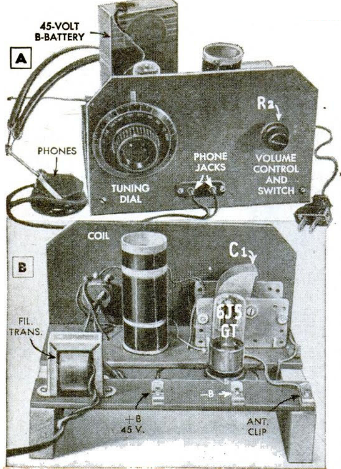

B.H. Standley, W5FQQ, on the air at city hall, along with city clerk Ernest Smith, Nurse Mrs. E.L. Brockman.

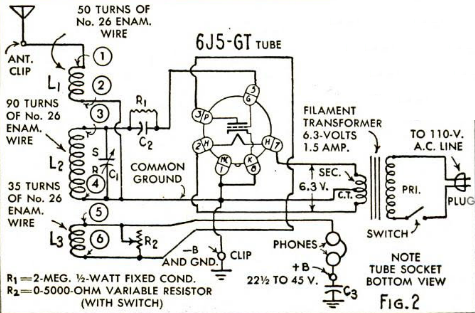

By noon, the first amateur portable and mobile stations had moved into the city and were on the air, working in conjuction with Army, Navy, Coast Guard, U.S. Engineers, FBI, and local and state police. Links were quickly set up between City Hall and stations in Houston and San Antonio. Most traffic was handled on 75 meter phone and 80 and 40 meter CW. W5KMZ reportedly handled over 200 messages, mostly involving needed medical supplies. As the hours went on, additional traffic was handled by W5FQQ at the mayor’s office, with over 300 messages passing on behalf of city officials, the Army, Red Cross, and Salvation Army.

An impromptu three-way net was established on 3989 kHz between Texas City, Galveston, and Houston.

Two hams, W5FQQ and W5EEX, had been advised to evacuate but remained at their stations. They narrowly escaped death when the High Flyer lived up to its name with its explosion. W5FQQ was on the air at the time of the blast, and the blast was heard by W5IGS in Houston. 21 seconds later, the Houston station experienced his windows shaking.

W1AW declared the emergency to be over 11 days later, on April 17.

As might be expected, considerable litigation followed, much of it under the Federal Tort Claims Act for alleged negligence of the U.S. Government. The case ultimately made its way to the U.S. Supreme Court, Dahelite v. United States, 346 U.S. 15 (1953), in which the court held that the Government was not liable, since all of the claimed government negligence amounted to discretionary acts.