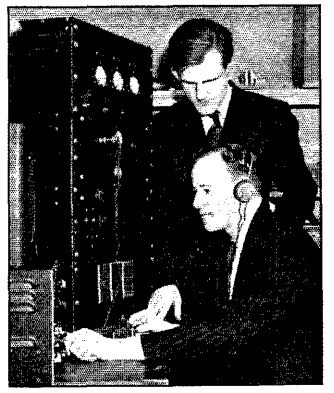

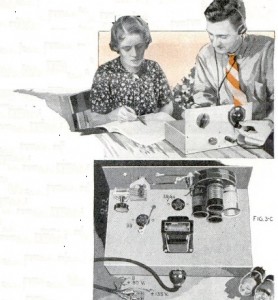

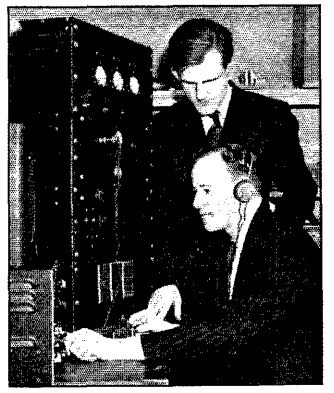

Sadowsky (seated, with headphones) and Gunderson. QST, December 1941.

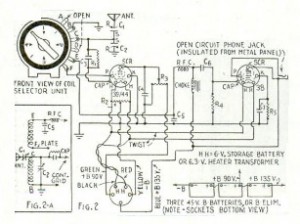

Seventy-five years ago, the December 1941 issue of QST carried a profile, authored by Clinton DeSoto, of a remarkable amateur radio operator, 21-year-old Leo Sadowsky, W2OFU. then of 482 Ashford Street, Brooklyn, New York. The remarkable fact was that Sadowsky was both deaf and blind, but despite his handicaps, he successfully obtained his license and was active on the air.

He was born deaf, and at the age of two, he lost the sight in one eye in an accident. At the age of sixteen, the “overburdened right eye also failed,” and he became totally blind.

Sadowsky’s instructor, Robert T. Gunderson, W2JIO, was an instructor at the New York Institute for the Education of the Blind. Gunderson was himself also blind. When Sadowsky first approached him to teach radio, Gunderson was at first skeptical whether it would be possible. Gunderson asked how he would hear the signals, and Sadowsky replied that he would take his word for it that the receiver was working correctly.

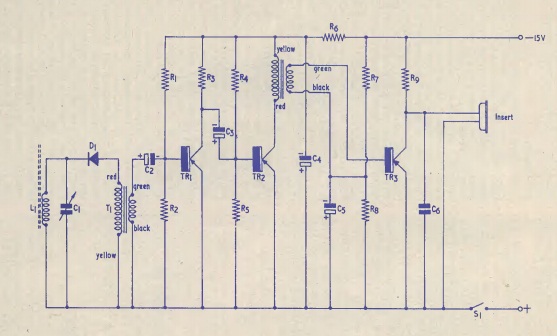

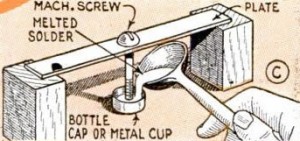

Sadowsky was able to learn code with a low-frequency buzzer, keyed by a relay connected to the receiver’s output. This was later refined to a 60 cycle tone that drove a pair of headphones whose vibrations he could feel. By the time he got his license, Sadowsky was able to build and operate his own equipment, and could copy code at 15-20 words per minute.

The FCC initially took the position that Sadowsky wasn’t eligible to sit for the code test, since the regulations specified that it be taken “aurally.” Gunderson argued that whether he could hear was beside the point, since he was taking the code test with a pair of headphones on his ears.

The exam, which Sadowsky took on July 1, 1941, was described as a “complicated procedure” owing to the fact that he “spoke” in a variety of ways. Before he had become blind, he and his brother had devised a wigwag system. To other blind persons, he talked by touching fingers and simulating the shapes of Braille characters. And the article noted that he was now capable of conversing by Morse code, either by tapping the wrist with a finger, or by “sound” through his headphones. For the code test, he dictated the text word-for-word to his brother, who wrote it down longhand.

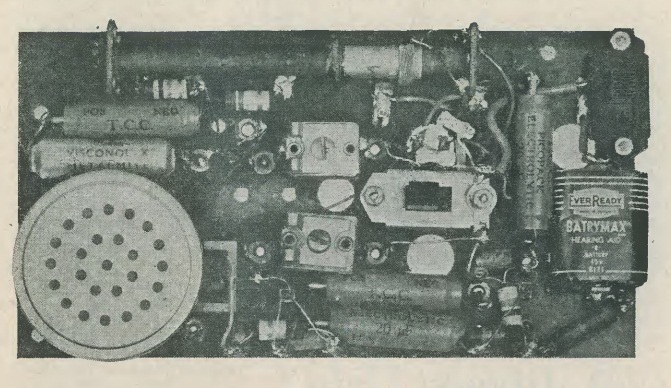

Gunderson then transcribed the written test in Braille, Sadowsky wrote them in Braille, and Gunderson rewrote them on a typewriter. The required diagrams were given in word form. The following Saturday, a telegram arrived from Washington informing Sadowsky that he had passed, and was now W2OFU. His station consisted of a 6L6 crystal oscillator running 25 watts and an ACR-136 receiver.

The QST article concluded:

Certainly Leo’s world is now vastly expanded beyond the small circle of family and Braille books and typewriter and a few blind friends; now he is in intimate contact with what must seem like the whole world.

An inspiring concept, that–the prospect of a normal and well-rounded life thus opened by the magic of amateur radio. Even more inspiring, however, is the demonstration of perseverance, ingenuity and indefatigable resolution exhibited by this young amateur and his mentor in the face of their combined handicaps. That’s the kind of spirit America needs.

Surprisingly, I’ve been able to find little subsequent information about Sadowsky. He is listed, at the same address, in the 1947 Call Book. He is not listed, at least in the second call area, in the 1949 Call Book or the 1956 Call Book. The Social Security Death Index does list a Leo Sadowsky of Queens, New York, born on February 24, 1920, who died in July 1992 at the age of 72.

While Sadowsky was apparently the first deaf-blind person to become a licensed radio amateur, he was not the last. Amateur radio has a long tradition of serving as a window to the world for those with disabilities. One of the best sources of support for persons with any kind of disability who are interested in radio is the Courage Kenny Handiham Program, which provides practical support to disabled persons wishing to earn their licenses and get on the air.

References

With America’s entry into the war, the nation’s broadcast stations were essential to inform and warn the public, and to maintain morale. As such, they were placed under military protection.

With America’s entry into the war, the nation’s broadcast stations were essential to inform and warn the public, and to maintain morale. As such, they were placed under military protection. The transmitter site remains at the same location today on the east side of U.S. Highway 61 in Maplewood, MN. The modern image here is the Google street view.

The transmitter site remains at the same location today on the east side of U.S. Highway 61 in Maplewood, MN. The modern image here is the Google street view.