Milwaukee Civil Defense Director Don E. Carleton and Col. Anthony F. Levno assess damage after simulated attack on Milwaukee. Milwaukee Journal, Jul. 20, 1956.

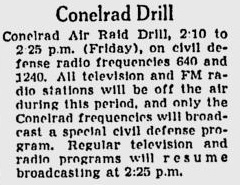

At 3:10 PM Eastern Standard Time on July 20, 1956, CONELRAD conducted its first (and as far as I can tell, only) nationwide test. At that time, all radio and television stations left the air for 15 minutes, and the only broadcast signals coming from the United States were those of the CONELRAD system on 640 and 1240 kHz.

CONELRAD was obsolete almost as soon as it was put into effect, but the idea was that during an enemy attack, attacking bombers must be deprived of the ability to use American broadcast stations for direction finding and navigation. Aviation routinely made use of AM stations for navigation, and the locations of broadcast stations and their frequencies are still printed on aviation charts. It was a reasonable concern, but it became much less critical when the bomber was replaced by the ICBM as the main component of both Soviet and American strategic war planning.

CONELRAD was created by President Truman in 1951, and hung on until 1963, when it was replaced by the Emergency Broadcast Sytem, in which participating stations continued to broadcast on their normal frequency.

Under CONELRAD, all stations in the U.S. would operate on the same two frequencies. The navigator of an enemy bomber tuning to either of those frequencies would be confronted with hundreds of stations on the same frequency, rendering them useless for navigation. And each station would transmit for only a few seconds or minutes. In smaller markets with only one station, the station would quickly give instructions, and then sign off for a few minutes. In larger cities, the stations would be linked together by telephone lines. A continuous program could be sent, but it would switch quickly from one transmitter to another, hopelessly confusing enemy bombers.

But for those 12 years, CONELRAD was the method by which Americans would be warned of war, and in 1956, it was put to a test. At 3:10 PM Eastern Time, each participating station was to transmit the program which had been delivered by record. The introduction to this broadcast can be heard at the following YouTube video:

In many cities, such as Chicago, the CONELRAD test was conducted in conjunction with other civil defense exercises. The Chicago Tribune for July 20, 1956, details some of the preparations being made there. The next day’s paper reports 325,000 simulated deaths in the Land of Lincoln.

There was surprisingly little reporting on how well the test went: Namely, whether the public was actually able to hear the broadcasts. One of the few actual tests was carried out by Radio News magazine, and reported in the October 1956 issue.

The magazine arranged receiving sites at four locations around the New York area. They were in a steel building in Brooklyn, a steel building in Manhattan, a home about 25 miles from the city, and a home about 50 miles from the city. At each location, writers for the magazine had multiple receivers ready for the test. They then rated the percentage of the broadcast they were able to receive intelligibly.

An outdoor antenna proved to be the greatest asset. At the home 25 miles from the city, the editor reported a 100% satisfactory signal using a Hallicrafters S-40 hooked to an outside TV antenna, and also with a Heathkit crystal set with a 100 foot outdoor antenna. At the same location, a Westinghouse battery portable without external antenna gave only 75% satisfactory reception.

In Brooklyn, the best performer turned out to be the Regency TR-1 transistor portable,

which gave a 100% reliable signal, but with continual retuning as the signal shifted from one transmitter to another. At the same location, the Knight tube portable was only 75% satisfactory, with the remaining signal too weak without reorienting and retuning the radio.

In Manhattan, the transistor portable, a Zenith Royal 500, outperformed the tube portable, with 85% satisfactory reception compared to 65%.

50 miles from the city, a Grundig tube portable gave 85% satisfactory reception, outdoing the Zenith portable, which had only 60% reliability. At this more distant location, the main problem came from interference from stations in other cities’ CONELRAD networks.

It is somewhat surprising that so much “retuning” was necessary. Presumably, the stations all had a crystal for their assigned frequency (the article didn’t state whether New York was using 640 or 1240), so it’s unlikely that the individual transmitters were drifting. More likely, some of the individual transmitters were slightly off frequency, resulting in the need to retune when the signal switched from one to another.

The article did stress the importance of having nondirectional antennas, something that was lacking in most AM portables. Most of the receivers, other than those using outdoor antennas, had to be reoriented when the signal switched transmitter locations. The article noted that extreme sensitivity wasn’t necessarily a good thing, because of the danger of interference from adjacent networks. These two factors explain why the crystal set had such good results in the test.

Click Here For Today’s Ripley’s Believe It Or Not Cartoon

![]()