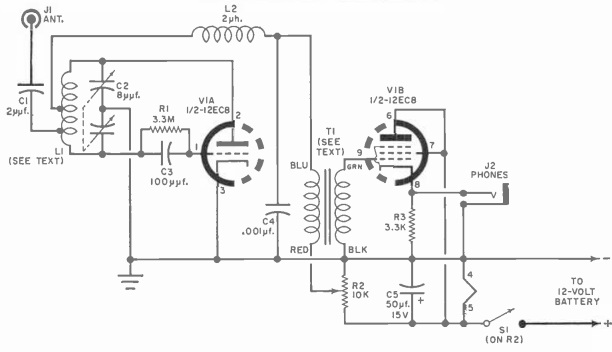

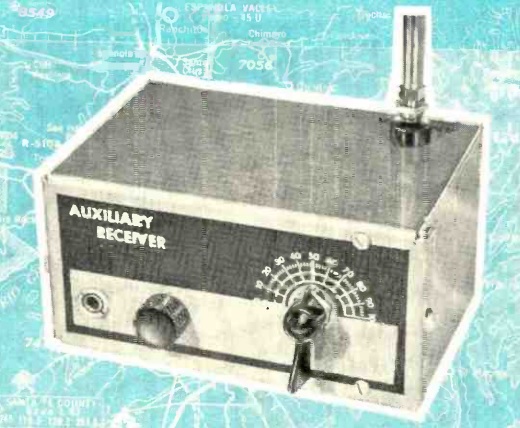

I’m not so sure that this little receiver is a good idea, but it is from the July 1962 issue of Popular Electronics. It’s a one-tube receiver covering 122-144 MHz, meaning that it mostly covers the air band. The problematic feature is that it’s a superregenerative receiver. And superregenerative receivers, in addition to being excellent receivers with great sensitivity, they also radiate a signal, in the form of a rushing noise, on the frequency that they are tuned to. So in addition to being able to hear airplanes in flight, the airplanes in flight might be able to hear you.

I’m not so sure that this little receiver is a good idea, but it is from the July 1962 issue of Popular Electronics. It’s a one-tube receiver covering 122-144 MHz, meaning that it mostly covers the air band. The problematic feature is that it’s a superregenerative receiver. And superregenerative receivers, in addition to being excellent receivers with great sensitivity, they also radiate a signal, in the form of a rushing noise, on the frequency that they are tuned to. So in addition to being able to hear airplanes in flight, the airplanes in flight might be able to hear you.

The author is aware of the problem, but asserts that “the power input to the detector is in the vicinity of 300 microwatts or less, so radiation should be of little concern.” That might be true, but I don’t think I’d want to risk it. Back in the day, I could hear my friend turning on his Heathkit Sixer a block away, since that receiver was also superregnerative. And if you used this receiver a block away from the airport, I bet you might have some splainin’ to do.

In any event, it’s a nice little receiver, which uses a 12EC8 tube. Since that tube was intended for use in car radios, it runs fine on 12 volts, and works well into the VHF range.