Washington Evening Star, Sept 1, 1939.

Today marks the 85th anniversary of the outbreak of World War II, with Germany’s invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939. Within days, Britain and France had declared war.

The outbreak of war meant that the BBC put into place a pre-arranged program to prevent its transmitters from being used by enemy aircraft for direction finding. All broadcasting was moved to two frequencies. Synchronized transmitters throughout the country transmitted simultaneously on those frequencies. During an air raid warning in one portion of the country, transmitters in that area would cease. But since other transmitters were still in operation, the listener would continue to hear the program, with only a modest loss of signal strength. Later in the war, another frequency, 1474 kHz, was added, with low-powered transmitters.

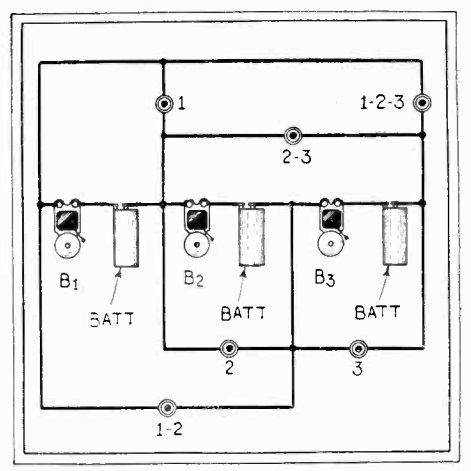

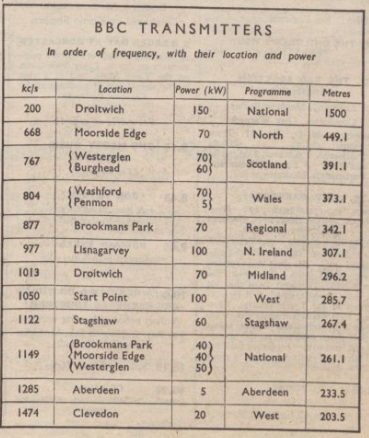

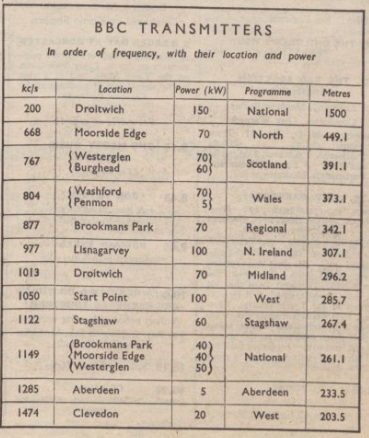

Immediately prior to the War, the BBC’s domestic programs were broadcast on the frequencies, shown at left, as shown in the September 1, 1939, issue of Radio Times:

Immediately prior to the War, the BBC’s domestic programs were broadcast on the frequencies, shown at left, as shown in the September 1, 1939, issue of Radio Times:

This consisted of a national program on 200 kHz longwave, and 1149 kHz mediumwave, as well as several regional programs. The following issue, dated September 4, entitled “Broadcasting Carries On,” highlighted the changes. The regional programs were suspended, and a single national program, called the Home Service, covered the whole nation.

The new Home Service would be on the air on 767 (North) and 668 kHz (South), starting at 7:00 AM until 12:15 AM. If important news warranted, there would be broadcasts at 1:00, 3:00, and 5:00 AM. Regional broadcasts were replaced with announcements for the respective regions. London and Scotland announcements would be at 6:15 PM, Welsh and Western announcements at 7:00 PM, Northern announcements at 7:45, and Midland and Northern Ireland at 10:45 PM.

The 200 kHz longwave signal went off the air, although it came back later for foreign broadcasts. The BBC’s television station in London also went dark for the duration of the War. You can read more of this history at the BBC website.

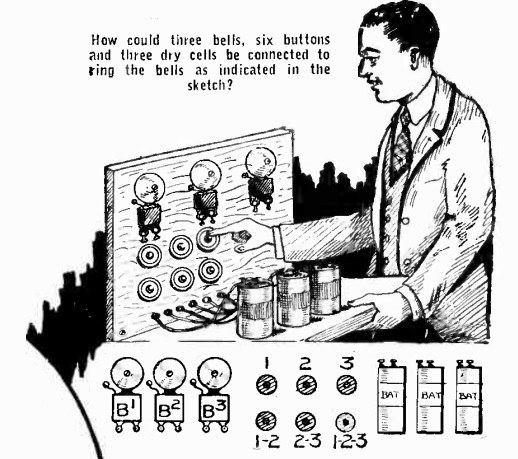

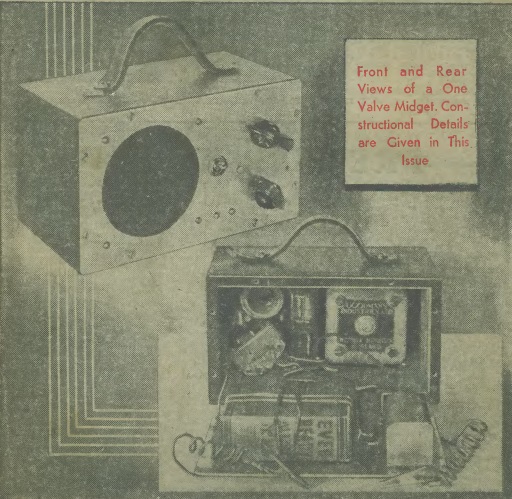

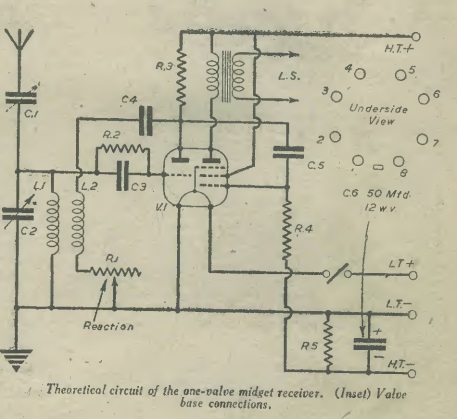

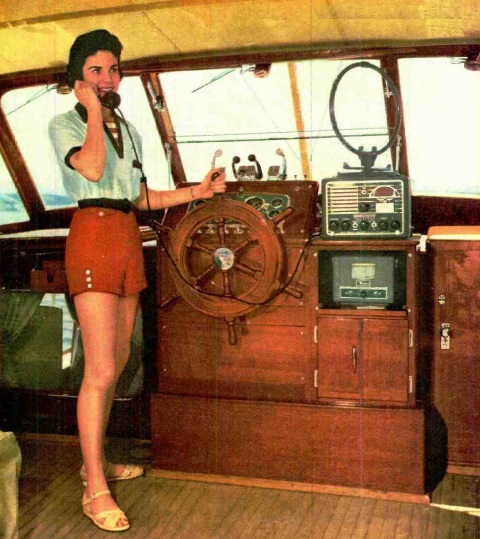

Seventy years ago, this mariner was placing a radio call from this well-equipped shipboard station. The transmitter is below deck, and shown on deck is the receiver and direction finder. The illustration appeared on the cover of the September 1954 issue of Radio-Electronics, which carried an article explaining how servicemen could take advantage of some recent FCC rulings to drive some business during the off season.

Seventy years ago, this mariner was placing a radio call from this well-equipped shipboard station. The transmitter is below deck, and shown on deck is the receiver and direction finder. The illustration appeared on the cover of the September 1954 issue of Radio-Electronics, which carried an article explaining how servicemen could take advantage of some recent FCC rulings to drive some business during the off season.