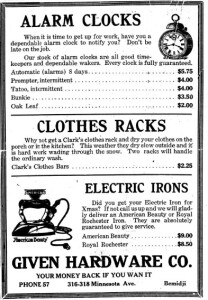

As you can see from the ad at the left, an alarm clock was a non-trivial expense a hundred years ago. This store, the the Given Hardware Company, 316-318 Minnesota Avenue, Bemidji, Minnesota, had models ranging in price from $2.00 to $5.75. That doesn’t sound like a lot of money, but according to this inflation calculator, that works out to a range of $28.92 to $83.14 in today’s money. If you had a clock in one room and wanted to hear the alarm in another room, going out and buying a new one would constitute an unnecessary expense.

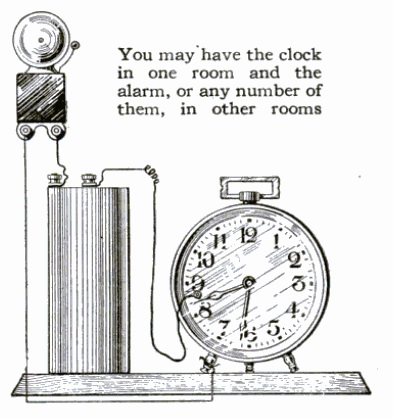

As you can see from the ad at the left, an alarm clock was a non-trivial expense a hundred years ago. This store, the the Given Hardware Company, 316-318 Minnesota Avenue, Bemidji, Minnesota, had models ranging in price from $2.00 to $5.75. That doesn’t sound like a lot of money, but according to this inflation calculator, that works out to a range of $28.92 to $83.14 in today’s money. If you had a clock in one room and wanted to hear the alarm in another room, going out and buying a new one would constitute an unnecessary expense.

You can compare that price to some of the perfectly functional, extremely accurate clocks below, all of which are probably orders of magnitude better than the 1921 model:

In fact, you can probably get a perfectly suitable alarm clock at the closest dollar store. So if you need an alarm clock in another room, or need a louder alarm clock, it’s a simple matter of going to the store or going to Amazon and just buying one.

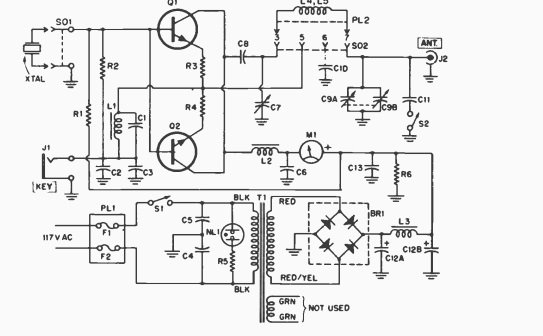

But a hundred years ago, it was a problem best solved by ingenuity, as shown by the self-explanatory idea shown above. This relied on the fact that the glass of most alarm clocks could be rotated, but would still hold its position. Therefore, a small hole was drilled in the glass and a machine screw was carefully inserted so that it would contact the hour hand, but not interfere with the minute hand. A small piece of spring brass wire was soldered to the hour hand to serve as a brush and make contact. The alarm could be set to any desired time simply by revolving the glass.

In case you’re wondering how much the doorbell cost, this 1918 Western Electric catalog showed them starting for about $1.30, and the dry cell battery was about 60 cents.

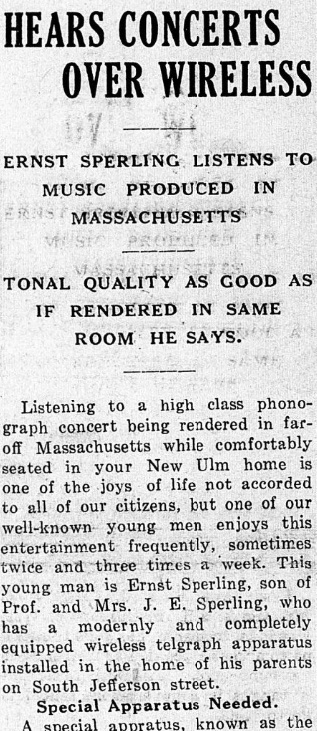

This idea appeared in the January, 1928, issue of Popular Science, and had been sent in to the magazine by one G.H. Rouse. The ad appeared in the Bemidji Daily Pioneer, January 4, 1921.