Pearl Harbor Anniversary

Today marks the 76th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941, marking the entry of the United States into World War II.

The Peace Light

As a symbol of peace, we show the flame above, which has been burning for hundreds of years. This flame was burning throughout the Second World War, the First World War, the U.S. Civil War, and every other war in modern history. It’s shown here in my living room, but it originates from the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, where it has been continuously tended for hundreds of years. The exact date that some monk struck a flint to ignite it is not known, but it is believed to be about a thousand years ago.

Each year during the Advent season, it is transported from Bethlehem to Europe and North America, courtesy of Austrian Airlines. This year, it was brought to Kennedy Airport on November 25. From there, volunteers fan out across the country to distribute the flame. Most of these are connected with Scouting in some way, and Scouts and Guides in Europe participate in similar activities.

As I did last year, I played a small part in the distribution. Prior to my getting it, the flame traveled to Indianapolis, and then to Chicago. From there, it went to Des Moines, and I met an Iowa Scouter in Albert Lea, Minnesota, to transfer it to St. Paul. From me, it was picked up by others who took it to Wisconsin and North Dakota. From there, it will travel to Winnipeg, and probably to other points. Meanwhile, others are taking it to other parts of the United States, Canada, and Mexico.

You can read more about the Peace Light at the U.S. Peace Light website or the Peace Light North America Facebook group. If you’re close to St. Paul, Minnesota, and would like to receive the Peacelight, feel free to contact me and we can make arrangements. In other areas, you can find a local source on the Facebook page.

Lanterns

One common question is how the Peace Light travels on two international flights from Israel to Austria, and then to North America. The flame is transported safely in an antique blastproof miner’s lamp. On the ground, it is walked through customs by airline employees to the airport chapel.

On the ground, the most common way to transport the light is with a lantern such as the one at the top of the page. These are rarely used these days, since mantle type lanterns provide considerably more light. But in the 19th century, the cold-draft kerosene lantern was something of a revolution in lighting, since it provides a fairly bright flame and is also relatively safe, since it will self-extinguish if tipped over.

A good history of the lantern can be found at this site. Prior to such lanterns, the best available option for camp lighting was the candle lantern. As the name implies, it was just a ventilated enclosure in which a candle was inserted.

The ad at the left, from the June 1916 issue of Boys’ Life, shows both types of lamps. The candle lantern here is known as a “Stonebridge” lantern, since it was manufactured by a company of that name, and replicas have been made over the years. Interestingly, in addition to providing more light, the kerosene lantern is actually less expensive. Candle lanterns start at $1.50, but the cold-blast lantern is only 75 cents.

Both types of lanterns are readily available today. The cold-blast kerosene lantern can be found at Amazon at any of the following links:

You can also obtain the lantern at WalMart with this link or this link. The fuel is available at this link. You can order the lanterns and fuel online with these links, and then pick them up the same day at the store.

And for those who want to be even more retro in their camp lighting, these candle lanterns are also available at Amazon:

The replica Stonebridge lantern shown below is very similar, or possibly identical, to the 1916 candle lantern shown in the ad:

How to Transport the Peace Light

How to Transport the Peace Light

If you need to transport the flame only a short distance, one good option is to use a votive candle at the bottom of a coffee can. For longer distances, I place the lanterns at the top of the page inside a 5 gallon bucket similar to the one shown at the left, wtih sand or cat litter at the bottom.

If you need to transport the flame only a short distance, one good option is to use a votive candle at the bottom of a coffee can. For longer distances, I place the lanterns at the top of the page inside a 5 gallon bucket similar to the one shown at the left, wtih sand or cat litter at the bottom.

Carrying it in this manner is very stable, and I have never experienced it tipping. If it does tip, the entire lantern is safely contained, and the lantern will self-extinguish.

It should be noted that because there is an open flame, you should not refuel the vehicle with the Peace Light in the car. Fill up your gas tank before picking up the light. If you need to buy gas before you reach your destination, it will be necessary to leave the lantern at a safe location before driving to the pumps. And while the combustion of these lanterns is very complete, it is a good idea to keep a window of the car open slightly.

Plans for a more a elaborate carrier are also available at the Peacelight.org site.

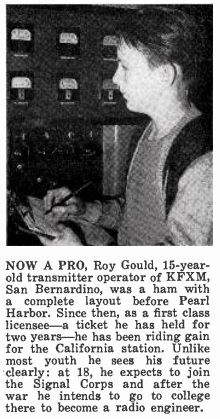

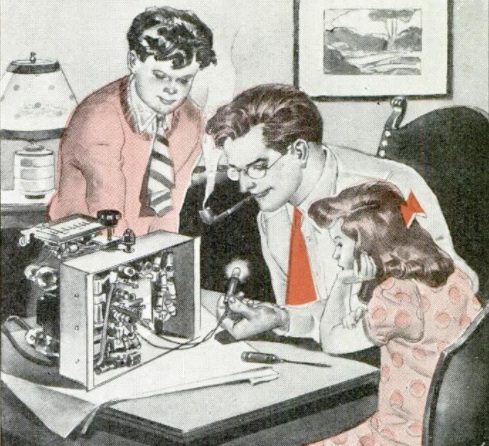

75 years ago this month, this father, shown in the December 1942 issue of Popular Mechanics, engages in some troubleshooting of the family’s radio receiver while the kids look on admiringly.

75 years ago this month, this father, shown in the December 1942 issue of Popular Mechanics, engages in some troubleshooting of the family’s radio receiver while the kids look on admiringly.