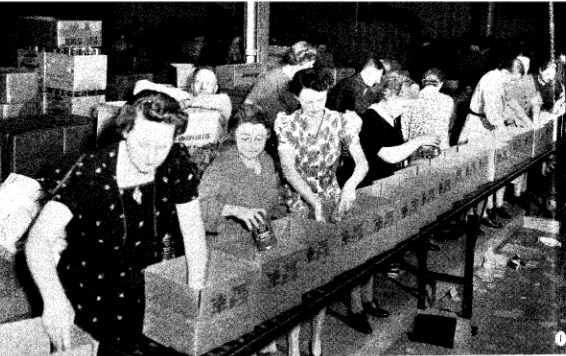

The Canadian women shown here are volunteers packing prisoner of war Red Cross food parcels on their way to Canadian POWs, primarily in Germany and Italy.

The Canadian women shown here are volunteers packing prisoner of war Red Cross food parcels on their way to Canadian POWs, primarily in Germany and Italy.

The photo appeared in the October 1943 issue of Manitoba Calling, the magazine and program guide of CKY Winnipeg. It shows the Red Cross packing plant in Winnipeg, the largest of five in Canada. The plant was staffed five days a week by volunteers and turned out food parcels at a rate of 4400 per day. The plant was described as businesslike, with two long conveyor belts. As the parcels moved down the line, a woman placed a food product in the same spot in each box. Items were picked for their nutritive values, and included chocolate, raisins, tinned butter, and corned beef. An acknowledgement card was included in each parcel, which were signed by prisoners and returned by mail to the Canadian Red Cross as proof of delivery.

From Canada, the parcels went by sea to Lisbon. From there, they were taken by Red Cross ships to Marseilles and then by train to Geneva to the warehouses of the International Red Cross. From there, they were distributed within the enemy countries.

The magazine noted that many of the volunteers were related to prisoners, 900 of whom were Manitoba boys.