Thankfully, nothing happened 75 years ago today, August 22, 1945. The war ended before the scheduled event could take place.

In 1944, the Japanese War Ministry issued orders to prison camp commandants for the “final disposition” of Allied prisoners of war. Under those orders, all POW’s were to be killed at such time as Allied forces landed in the territory in which they were being held. The rationale behind the order was to prevent the POW’s from being repatriated and becoming a part of the liberating force.

For example, on December 14, 1944, about 150 prisoners of war at Palawan in the Philippine Islands, were ordered to the air raid shelters, at first in apparent response to an actual air raid. But after the raid, because of a mistaken belief that an invasion of the island was underway, they were ordered to remain, at which time the wooden structure was doused with gasoline and set afire.

According to the book Unbroken by Laura Hillenbrand

by Laura Hillenbrand , the date set for at least one camp on the home islands was 75 years ago today, August 22, 1945.

, the date set for at least one camp on the home islands was 75 years ago today, August 22, 1945.

That book is the story of Louis Zamperini, a record-breaking track star of the 1930’s. Among his claims to fame was a personal meeting with Hitler at the 1936 Olympics. In 1943, his plane crashed in the Pacific and he drifted in a small raft for 47 days until his “rescue” by the Japanese. He remained a prisoner until the end of the war, enduring much torture. After the war, haunted by nightmares of his experience, he drifted into alcoholism until attending a Billy Graham crusade in California.

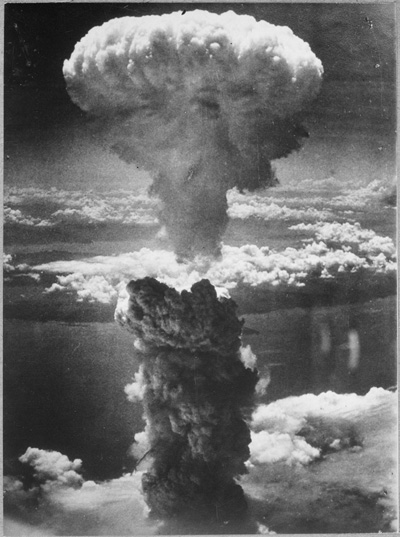

Because of the Japanese decision to surrender, motivated at least in part by the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the orders to execute Zamperini and other prisoners in Japan were never carried out.

References

Read More At Amazon

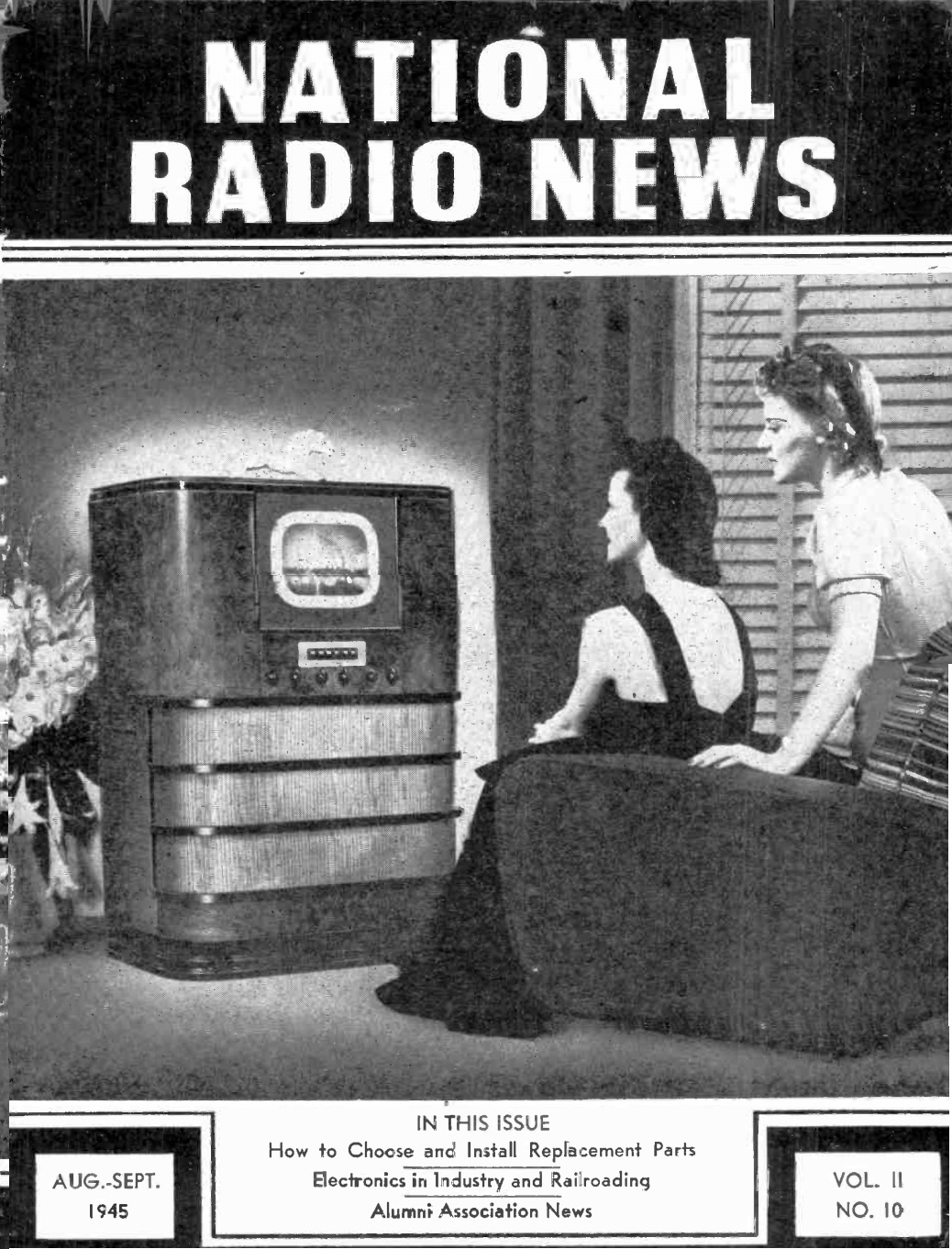

Seventy-five years ago this month, the September 1945 issue of Radio Retailing was a thick one–175 pages. It was packed with ads from radio suppliers announcing that new radio would be rolling off the assembly lines for the first time in over three years. There was a pent up demand, and it was going to be a great time to be a radio dealer.

Seventy-five years ago this month, the September 1945 issue of Radio Retailing was a thick one–175 pages. It was packed with ads from radio suppliers announcing that new radio would be rolling off the assembly lines for the first time in over three years. There was a pent up demand, and it was going to be a great time to be a radio dealer.