During the 2016 centennial of the National Park Service, the American Radio Relay League (ARRL) is conducting its National Parks On The Air (NPOTA) event. Amateur Radio operators are setting up their stations in various units of the National Park Service (NPS) and making contact with other Amateurs around the world. Since the beginning of the year, the event has been extremely popular, with over 11,000 activations from 450 different different units of the NPS (with only 39 not yet activated), with over 640,000 individual two-way contacts. As I’ve reported in other posts, I’ve made contact with 251 different parks, operated multiple times from six parks in Minnesota and Wisconsin, and plan to activate additional parks in the Midwest before the end of the year.

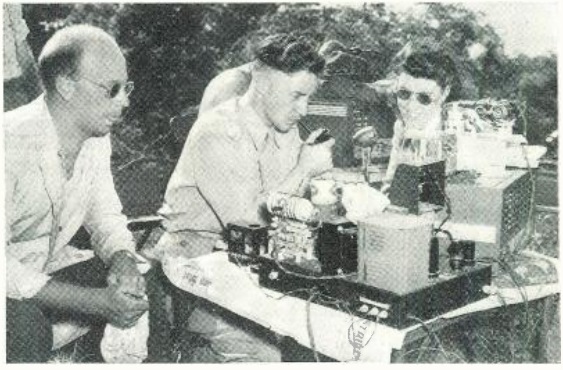

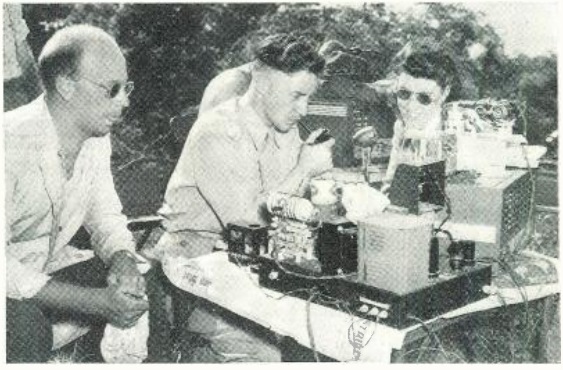

Even though this event is recent, operating portable from the National Parks is nothing new, as shown from the photograph above, which appeared seventy years ago this month in the September 1946 issue of Radio News.

Shown here are members of the Washington Radio Club operating Field Day 1946 from Shenandoah National Park in Virginia. Shown here are Dick Houston, W4QPW (apparently at the mike), along with Major Eric Ilott, G2JK, of the British Army (later VE3XE), and club secretary Barbara Houston. They are operating a 25 watt phone rig on 10 meters, with a Hallicrafters Sky Champion serving as the receiver. Power was supplied by a 300 watt gasoline generator.

Ilott, apparently at the left in the photo, served in the British and Canadian military until his retirement as a Lieutenant Colonel in 1974. He immigrated to Canada in 1947. During the war, he served as a listener for the British War Office, sending reports to Bletchley Park. Among his accomplishments after the war was bringing the first ever television signal to Kingston, Ontario, from an antenna atop a water tower. He died in 2015 at the age of 95. (For another look at the early days of bringing distant TV signals to town, please see my earlier post on the first TV in Marathon, Ontario.)

1946 was the tenth running of the ARRL Field Day, an event in which hams set up stations at portable locations to make as many contacts as possible.

I previously wrote about the 1941 Field Day, in which the high scoring station had made 1112 contacts. That would be the last Field Day before the war, and the one shown here was the first postwar Field Day. According to the results in the February 1947 issue of QST, the top 1946 scorer made 809 contacts.

But the results article noted that it would be pointless to compare the 1946 results with those of prewar Field Days, since operating conditions as of June 1946 were quite different. In particular, hams had not yet regained access to the 160, 40, and 20 meter bands, which had been the workhorses for the prewar events. The 1946 Field Day was limited to 80 and 10 meters on HF, along with the 50, 144, and 420 MHz bands.

Shenandoah was not the only national park being activated in 1946. In addition, according to the results article, there were operations from Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado and a battlefield national park in Virginia, as well as numerous other venues.

Photo courtesy of N3KN.

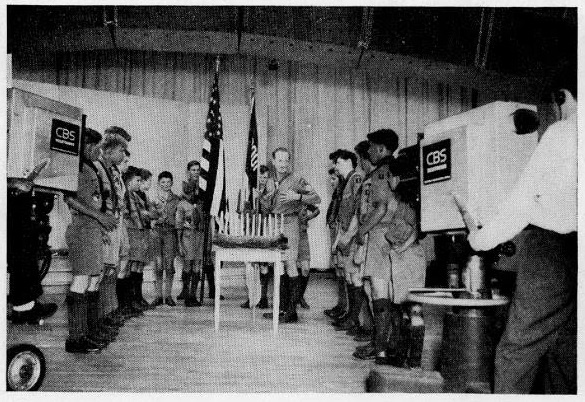

While the Washington Radio Club took the honors of activating Shenandoah National Park in 1946, my own 2016 contact took place on February 8 on 20 meter phone. Fortunately, the 20 meter band was returned to hams shortly after the war, as the contact on 10 or 80 meters in 1946 would have been considerably more challenging. My contact was with Kay Craigie, N3KN, shown here. In addition to being an avid NPOTA chaser, activator, and member of the NPOTA Facebook group, Kay is the immediate past president of the ARRL (a select group which included Herbert Hoover, Jr.). She was at the helm of the ARRL when the NPOTA event was proposed and adopted.

Click Here For Today’s Ripley’s Believe It Or Not Cartoon