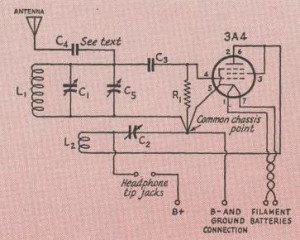

Installing the antenna.

I rarely get a chance to experience a “pileup” on the radio, but today I was able to. As I recounted in an earlier post, the ARRL is sponsoring an event called National Parks on The Air in which hams are encouraged to operate from units of the National Park Service and to make contact with those stations. In addition to the 59 National Parks, this includes other units of the National Park Service. Two of these are located within a few miles of my house, the Saint Croix National Scenic Riverway and the the Mississippi National River and Recreation Area. Under the ARRL rules, as long as the station is within 100 feet of one of these rivers, it qualifies.

My assistant operator.

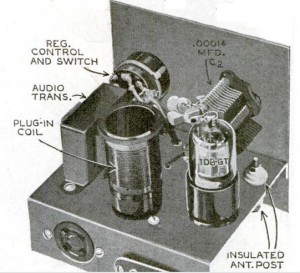

A close examination of Google Maps revealed that most of the parking lot of the Saint Croix Boom Site near Stillwater is within 100 feet of the river. In addition, it’s at a high location above the river, which is better suited for radio transmissions. And until today, nobody had activated this unit. So this afternoon, along with my daughter, I set out for this location. As with my previous activation, my station consisted of my Yaesu FT-817into a Hamstick mobile antenna

mounted with a trunk mount

. The antenna, about six feet long, is shown in the photo at the top of this page.

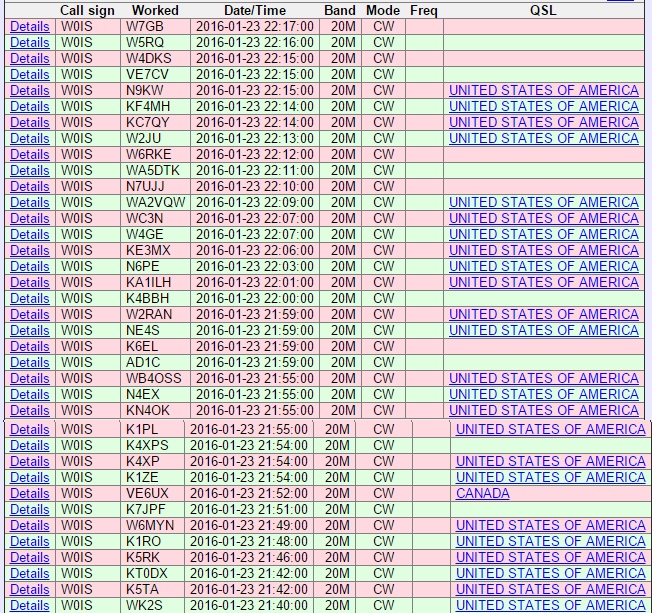

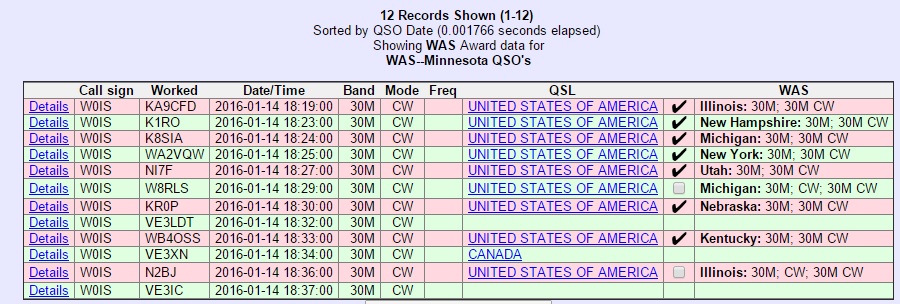

Today, I operated for only about a half hour, but was almost immediately confronted with a pileup. In just over thirty minutes, I worked 36 contacts:

Since I was on 20 meters, I had few, if any, contacts within a few hundred miles. On that band, those close-in contacts are within the “skip zone,” meaning that the signals are reflected by the ionosphere only much further distances. I believe my closest contact was Colorado, but I had contacts with locations such as California, Alberta, and New Hampshire. The amazing thing is that I was using only five watts of power. I was getting the power from the car (which I kept running for heat), but I could have just as easily made all of those contacts with the radio’s internal 8 AA batteries. And my antenna, only about five feet long, is grossly inefficient. In addition, as you can see from the photo, it was partially blocked by the car itself. But it goes to show that if hams really want to make the contact, they’ll listen for the weak ones.

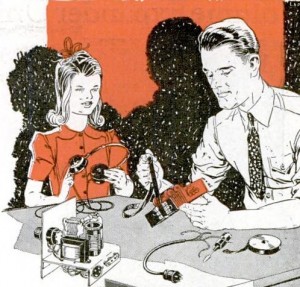

Google Street View of my operating location.

Living in the city, it’s easy to forget how close some of the natural wonders of the area really are. and Saint Croix National Scenic Riverway includes a lot of gems. In addition to the National Park facilities, at least four Minnesota State Parks border the river: William O’Brien, Interstate, Wild River, and St. Croix. I’ve already identified several sites in their campgrounds that are within a hundred feet of the water, and I will almost certainly make more activations later in the year from one of these spots.

The site from which I was operating today is the Saint Croix Boom Site, which is just north of Stillwater on Highway 95. In fact, downtown Stillwater is visible as you look down the river. But as you look upstream and at the Wisconsin side, it’s clear that you’re at the beginning of the wilderness.

The historic marker at this site commemorates the St. Croix Boom Company, which was chartered by the Minnesota Legislature in 1851. The St. Croix River Valley was a major logging area, and the loggers floated the logs down the river to mills. Each logging company’s harvest was marked with a timber mark, and the St. Croix Boom Company was granted its charter to collect all logs and deliver them to their owners. At the location where I operated today, the company operated a series of “booms”–logs chained across the river, to catch the lumber as it floated downstream. Workers gathered logs and formed logs of each company into rafts, which were steered downstream to the correct mill, some as far south as St. Louis. In exchange, the company was granted the right to charge 40 cents per thousand board feet. The photo below shows the Boom Site in operation in about 1886.

Minnesota Historical Society photo, via Wikipedia.

Today, the site consists of three stops on Highway 95. In addition to the historical marker from which I operated today, there is a stairway leading down to the river, a modern rest area just to the north, and a public access boat launch just to the south. The site also marks the transition between the federal and state zones of the river. Upstream to the north, the river is under the jurisdiction of the National Park Service. Downstream to the south, the river is still designated as the Saint Croix National Scenic Riverway, but is under the jurisdiction of the Minnesota and Wisconsin Departments of Natural Resources.

Winter weather precludes many outdoor operations, but even with cold temperatures, operating mobile from a warm car is a fun way to get out and get on the air. My next such operation will probably be from the

Winter weather precludes many outdoor operations, but even with cold temperatures, operating mobile from a warm car is a fun way to get out and get on the air. My next such operation will probably be from the