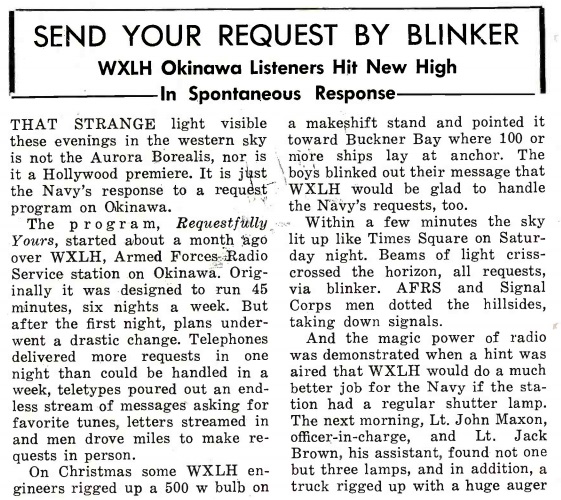

WW2-era signal lamp. Wikipedia photo.

The taking of requests has been a long-standing tradition in the broadcasting industry. Most typically, the requests come in by phone, but other methods are possible, as shown in this item from Broadcasting magazine 75 years ago today, January 21, 1946.

WXLH, the Armed Forces Radio Service station in Okinawa, which had come on the air on May 17, 1945, carried a request program, originally slated to run 45 minutes six nights a week. The program was widely popular with servicemen, and requests poured in by telephone, teletype, mail, and in person.

Buckner Bay. Wikipedia image.

Left out, however, were the sailors on the hundred or more ships anchored in Buckner Bay. To accommodate them, on Christmas, some of the station’s engineers rigged up a 500 watt bulb on a stand and pointed it toward the bay. They blinked out a message that the station would be happy to take Navy requests as well.

The sky lit up within minutes with beams of light crisscrossing the horizon. AFRS and Signal Corps men dotted the hillsides and took down the requests.