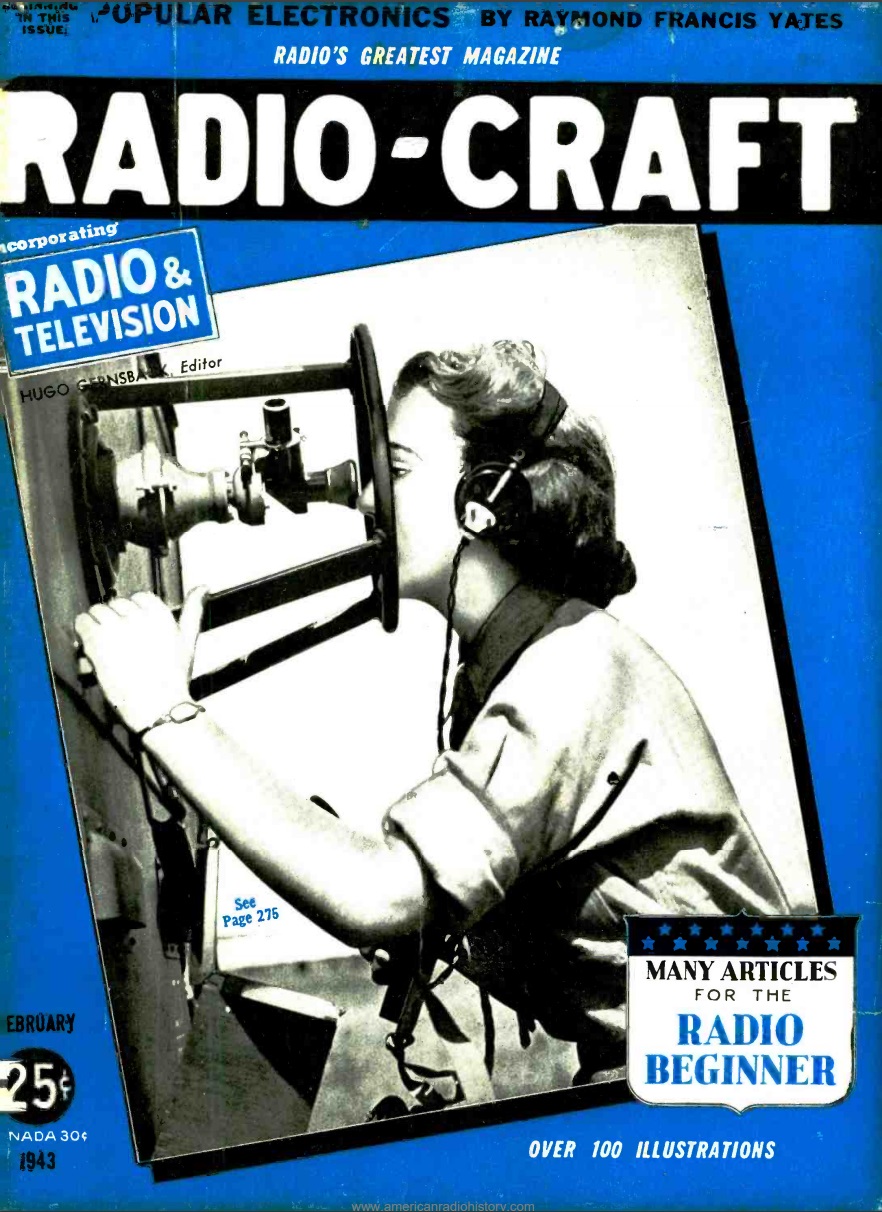

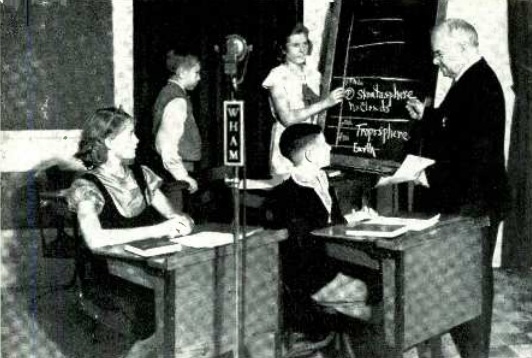

The students shown here are now almost 100 years old, but 85 years ago, they were learning about the atmosphere in science class. These students, Marian Oakley, Henry Kehrer, Hannah Esterman, and Bruce Kunkel, were receiving instruction in person from science specialist Harry A. Carpenter, but hundreds of other students were taking part in the same class by radio, on station WHAM.

The students shown here are now almost 100 years old, but 85 years ago, they were learning about the atmosphere in science class. These students, Marian Oakley, Henry Kehrer, Hannah Esterman, and Bruce Kunkel, were receiving instruction in person from science specialist Harry A. Carpenter, but hundreds of other students were taking part in the same class by radio, on station WHAM.

For several years, the Rochester, NY, schools had been conducting this sort of distance learning via radio. Afternoons, radios would be switched on in classrooms both in and outside of Rochester, and students would get their lectures by radio. Lessons could include well known guest speakers, music programs featuring the Rochester Civic Orchestra, and programs on books presented by the Rochester Public Library. The photo shown here appeared in the February 1938 issue of Rural Radio, and the students shown here attended Frank Fowler Dow School No. 52.