We were sad to hear the news recently that MFJ Enterprises will be shutting down production on May 17, 2024. The company has long been a fixture in Amateur Radio, producing a wide variety of products, mostly station accessories, for the amateur market. Their products have the distinction of being functional and utilitarian, and usually reasonably priced. They are often dubbed “Mighty Fine Junk,” but it’s a term of endearment, with the emphasis on “mighty fine.” They are junk in the sense that they are usually not professional grade. But they usually serve their purpose well, and they will be missed.

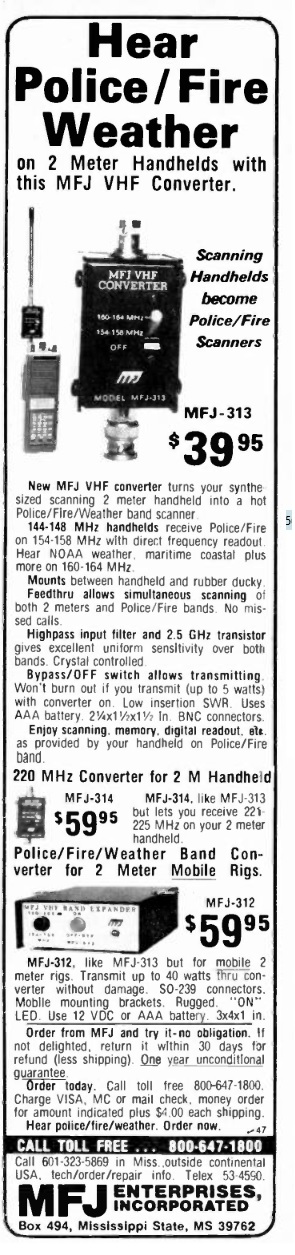

My first encounter with MFJ was probably the product shown at left, which is typical of their offerings: It met a very specific need at a reasonable price. It looked kind of clunky, but it worked well. When the MFJ-313 VHF converter came out in 1982, inexpensive handheld radios for 2 meters were just hitting the market. For example, my first HT was an Icom IC-2AT, which was priced at about $225. Unlike most ham rigs these days, the radios of that era generally tuned only the ham bands. So receiving was limited to 144-148 MHz.

The ability to tune other frequencies, particularly NOAA Weather on 162 MHz, was a useful addition, and the MFJ-313 solved that problem. It was a receive converter, powered by a single AAA battery, that attached to the radio and antenna. You could transmit right through it, “and it won’t burn out.” But at a flip of a switch, the local oscillator inside the converter would come to life at 16 MHz, and you would be able to tune the weather on 162.55 by tuning the receiver to 146.55.

Most of MFJ’s products filled similar niche needs. They weren’t glamorous, but they got their job done.

Another MFJ product I own is the MFJ-9040 CW transceiver for 40 meters. There was a time when I had been off the air for a few years, and didn’t really have a station set up. I wanted to get on the air fast, and this rig did the trick. I’ve traveled to multiple countries with it, and it’s always performed well. It’s not a perfect rig–it’s notorious for having a lot of frequency drift when first turned on. But that’s part of the charm, and the drift isn’t too bad once it’s been turned on for a while.

You wouldn’t build your whole station using MFJ gear (although with rigs like the 9040, you certainly could). But they took care of all kinds of needs.

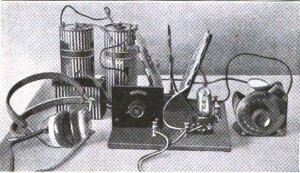

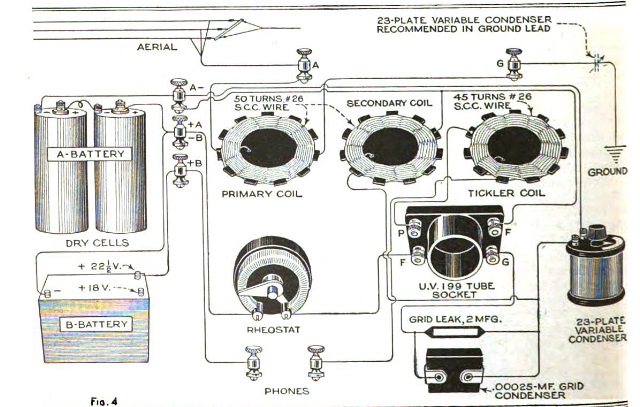

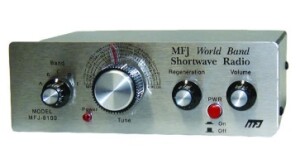

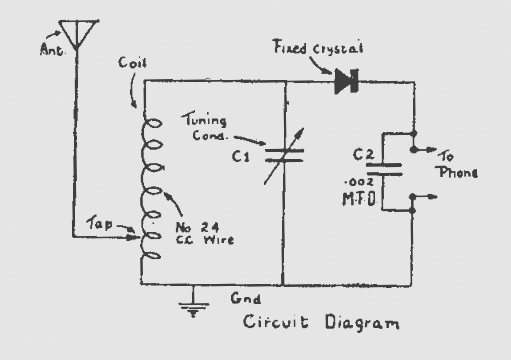

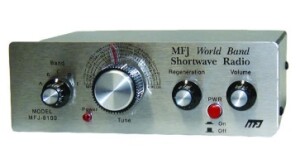

If you’re still interested in getting in on the fun, the company isn’t going out of business just yet, and they undoubtedly have a lot of New Old Stock on hand in their warehouse, and at their many dealers. If you want to build something, I would recommend their MFJ-8100K regenerative receiver. It covers shortwave broadcast and amateur bands from 80 to 15 meters, and should be a relatively easy kit for the beginner. It’s also available assembled.

If you’re still interested in getting in on the fun, the company isn’t going out of business just yet, and they undoubtedly have a lot of New Old Stock on hand in their warehouse, and at their many dealers. If you want to build something, I would recommend their MFJ-8100K regenerative receiver. It covers shortwave broadcast and amateur bands from 80 to 15 meters, and should be a relatively easy kit for the beginner. It’s also available assembled.

I suspect that some of MFJ’s brands will be sold to other manufacturers, and it’s not all doom and gloom. Those other little accessories they make, even if MFJ stops making them, will still be available. For example, I really like my MFJ-9040, but QRP Labs has a superior product in the QCX Mini, which I previously reviewed. We will miss MFJ, but amateur radio will continue.

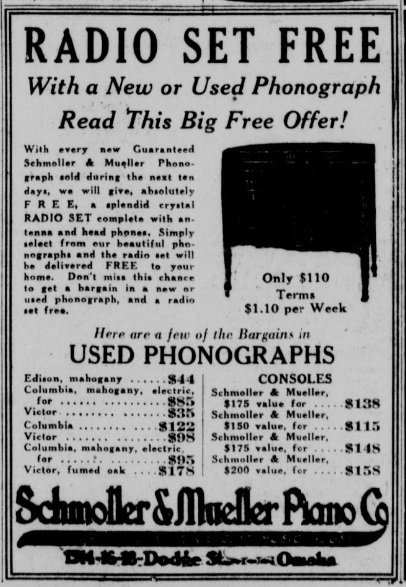

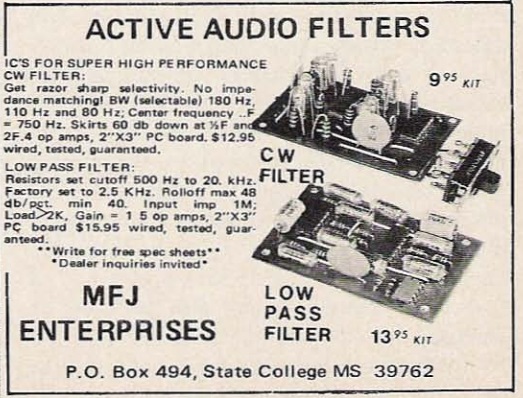

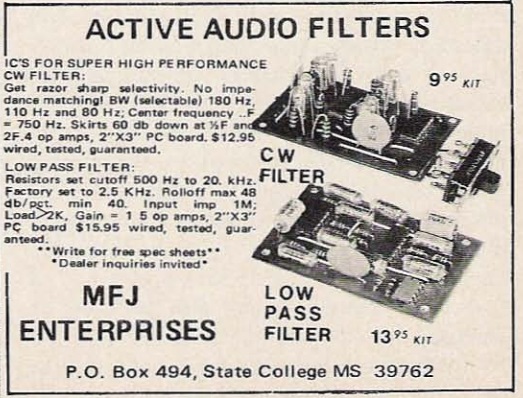

MFJ got its start in 1972, and as far as we can tell, it’s first products were the two audio filters shown in this ad in 73 Magazine, December 1972. They made an innovative product, and kept adding more innovative products. We’re confident that someone will do it again.

MFJ got its start in 1972, and as far as we can tell, it’s first products were the two audio filters shown in this ad in 73 Magazine, December 1972. They made an innovative product, and kept adding more innovative products. We’re confident that someone will do it again.

We thank MFJ’s founder and owner, Martin F. Jue, K5FLU, for over a half century of service to the Amateur Radio Community, and wish him the best in his retirement.

Some links on this site are affiliate links, meaning that this site earns a small commission if you make a purchase after using the link.

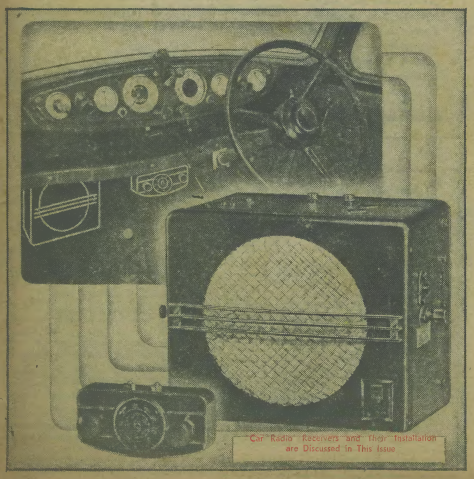

Eighty years ago, somewhat to the surprise of many in the industry, the British government lifted the sartime ban on radio receivers installed in cars. This was welcome news to those who still drove a car for essential purposes. And it meant that the price of secondhand auto radios in dealer’s stocks suddenly increased in price.

Eighty years ago, somewhat to the surprise of many in the industry, the British government lifted the sartime ban on radio receivers installed in cars. This was welcome news to those who still drove a car for essential purposes. And it meant that the price of secondhand auto radios in dealer’s stocks suddenly increased in price.