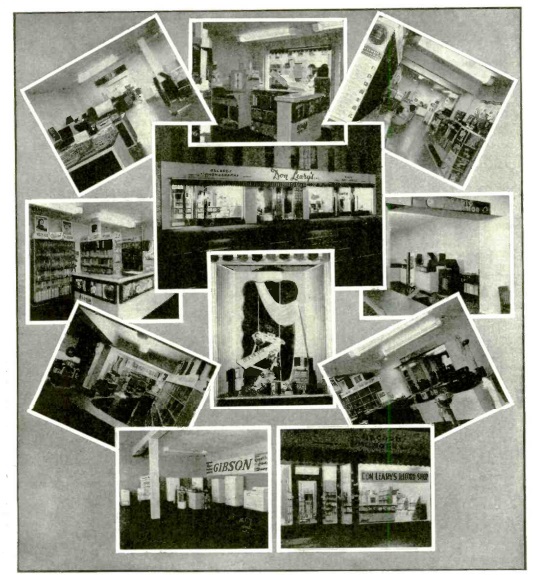

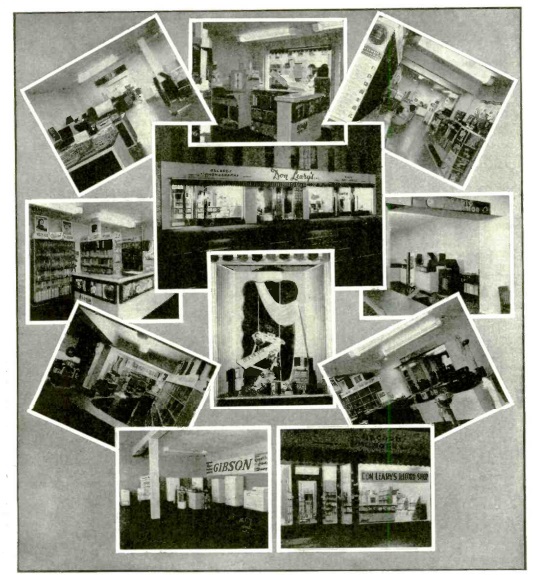

Shown here from 75 years ago are some views of Don Leary’s record store in Minneapolis. These images appeared originally in an issue of the store’s 12-page Don Leary Record News, which went out to over 25,000 people every month. The image was reprinted in the April 1947 issue of Radio Retailing., and that magazine highlighted the store’s ongoing advertising campaign, and the monthly newspaper was a key part of that advertising. The emphasis was on records bulletins and lists, but also highlighted the other aspects of the store’s business, namely, radio, appliances, and service.

Shown here from 75 years ago are some views of Don Leary’s record store in Minneapolis. These images appeared originally in an issue of the store’s 12-page Don Leary Record News, which went out to over 25,000 people every month. The image was reprinted in the April 1947 issue of Radio Retailing., and that magazine highlighted the store’s ongoing advertising campaign, and the monthly newspaper was a key part of that advertising. The emphasis was on records bulletins and lists, but also highlighted the other aspects of the store’s business, namely, radio, appliances, and service.

The store had over a quarter million records in stock, and its business philosophy was that the logical place to buy a radio or phonograph was where you bought your records. It was good business, since the satisfied customer would keep coming back for records.

In addition to its own newspaper, Leary reported that the store was the largest user of newspaper advertising space of any record store in the region. He also made a point of having friendly relations with reporters, who came to quote him as the expert in all things involving records. For example, he had recently been quoted in the Minneapolis Star-Journal regarding juke boxes, which he viewed as a good thing for the welfare of city youngsters. (Incidentally, it was an industry in which he was also involved.)

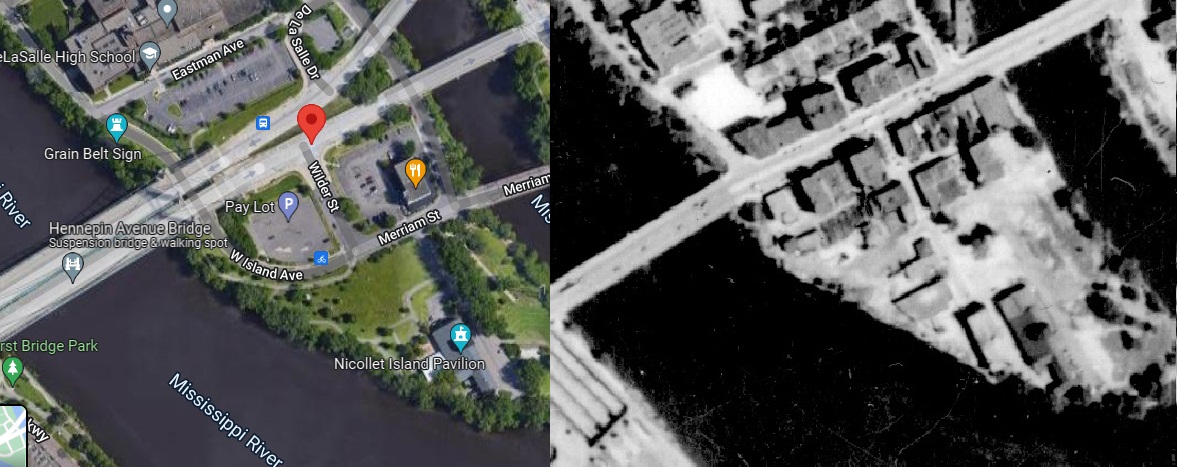

More biographical information about Don Leary can be found at this link. The store was opened in 1941 at 56 East Hennepin Avenue, on Nicollet Island. That address doesn’t really exist any more, but would be at the spot indicated on the Google Maps image below:

The aerial view at the right was taken in 1940, and shows a business district along East Hennepin, the street connected to the mainland by the two bridges. Over the years, East Hennepin was paired up with First Avenue Northeast as complementary one-way streets. On the island, they form a short four-land divided road, and there are no lots directly adjoining it. To the North, there is now a view of De La Salle High School, and to the South, there is now a view of the Nicollet Island Inn, both of which would have been obscured by buildings on East Hennepin in the 1940’s. Leary’s store would have been one of the buildings on the South side of the street, probably the fourth one from the left.

I write about a lot of people on this site, and I think this is the first time I’ve written about someone who I personally met back in the day. I believe East Hennepin got its current configuration through the island in the early 1970’s, and Don Leary’s was long gone by the time I remember being there. However, from 1971 through 1979, he owned a record store in a small suburban strip mall at 2927 NE Pentagon Drive, St. Anthony, MN.

Despite the small size of that store, he probably still had a quarter of a million records in stock, of all genres. I was looking for something by Jimmie Rodgers, the Singing Brakeman (1897-1933). I asked Leary, who seemed to run the store as a one-man operation whether he had anything, and he asked me whether I actually meant the unrelated Jimmie F. Rogers, who was born the year the elder Rodgers died. When I let him know that it was the Singing Brakeman I was after, he commented something to the effect that he went way back, but showed me an assortment of his records.

Leary died in 2000 at the age of 92.

Life Magazine for this day 75 years ago, August 18, 1947, carried this ad featuring Metropolitan Opera mezzo-soprano Risë Stevens extolling the virtues of General Electric’s “natural color tone” line of radios.

Life Magazine for this day 75 years ago, August 18, 1947, carried this ad featuring Metropolitan Opera mezzo-soprano Risë Stevens extolling the virtues of General Electric’s “natural color tone” line of radios.