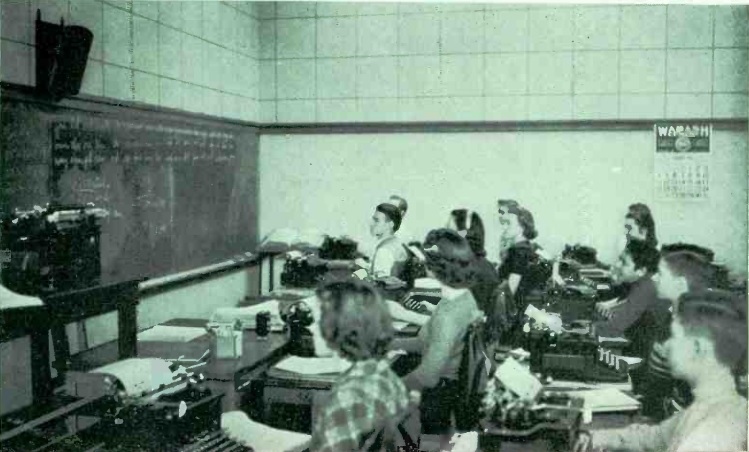

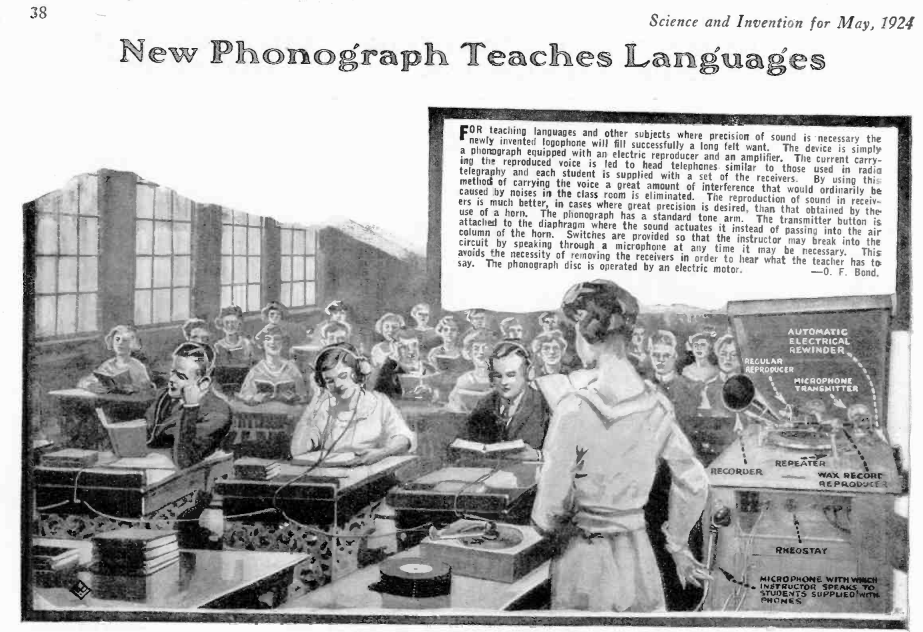

A hundred years ago this month, the May 1924 issue of Science and Invention shows the latest development in language education, namely, the photograph.

A hundred years ago this month, the May 1924 issue of Science and Invention shows the latest development in language education, namely, the photograph.

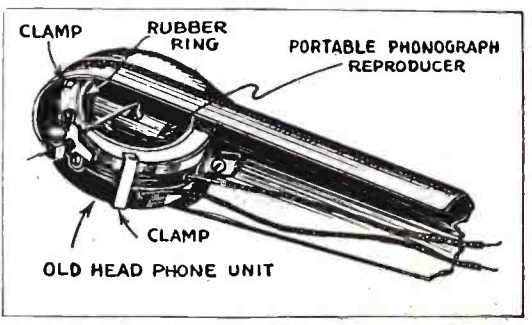

The main breakthrough here is that instead of listening through a horn, the phonograph reproducer contains a microphone, which is hooked to an amplifier feeding headphones for the individual students. The teacher is also supplied with a microphone, through which she can address the students without any need for them to remove the headphones.

The phonograph is also equipped to cut disks.