No, you don’t need a teaching license!

Among the many hats I wear, in addition to writing this blog, is that of substitute teacher. Depending on how busy my schedule is with other business, I teach in one of the Twin Cities area districts a few days a week. For many people, this is an excellent part-time job opportunity to make a few extra dollars, make a difference in the lives of students, and possibly find yourself energized by exposure to their youthful exuberance. The information on this page explains how to become a substitute teacher in Minnesota, although much of the information will be relevant in other states as well.

The rate of pay for this work varies from district to district, but in Minnesota, typically it is about $130 per day. Depending on the school, the substitute is expected to arrive about a half hour before the students arrive, and typically leaves about the same time as the students. This means that the substitute typically works about seven hours a day, and the afternoon is usually free. The mathematically astute will realize that this is almost $20 per hour, which isn’t too bad on days when I didn’t have anything else scheduled. There are also frequently half-day assignments available. During the day, the substitute usually has at least one “prep hour” available. During the prep hour, the normal teacher catches up on other work such as preparing lesson plans or grading papers. Since the substitute usually isn’t expected to do such things, this usually results in another hour during the day to catch up on other work. Since there is almost always a telephone and computer with internet access available, this can usually prove to be a productive time. Thus, even with the relatively low salary and lack of benefits, substitute teaching can be a reasonably lucrative proposition for many.

A person would certainly struggle to pay the bills if substitute teaching were their only source of income. But the schedule is so flexible that subbing can provide a great source of extra income for those who are self-employed or work another job in which they are free during the day.

For me, the main advantages of substitute teaching are:

- A source of income on days when I’m not working elsewhere.

- An opportunity to be an “insider” at my children’s own schools.

- The opportunity to make a real, albeit brief, positive impact on students.

For those who do need the income, it would be possible to work almost every day as a substitute. Jobs are available on an almost daily basis. For those who do not need to work every day, this allows you to be very selective on which jobs you take.

Minnesota Requirements

In Minnesota, anyone with a four-year college degree in any subject can become a substitute teacher. You do not need to have a degree in education. This is because many school districts have a shortage of substitute teachers. In Minnesota, a person with a four-year degree, but without an education degree, and receive a “Two Year, Short-Call Substitute” license.

This certificate is issued by the Minnesota Department of Education. There is a fee of about $93, and you will need to be fingerprinted as part of the application process. As the name implies, this permit is valid for two school years.

Even though you will need to obtain this state license, the starting point is the individual school district where you plan to work. This is because the two-year license is available only to persons teaching in districts where the superintendent has verified that the district is experiencing a hardship in locating fully licensed teachers. As far as I can tell, the license, once issued, is valid statewide. But to get the license in the first place, you will need the signature of a district superintendent verifying that district’s hardship.

Fortunately for you, many districts in Minnesota are experiencing such hardships, and they will be overjoyed to sign off on your license application. In fact, they routinely do this as part of the hiring process.

I have noticed that these “hardships” seem to come and go. For example, the district where I am currently teaching does not currently have this hardship. Therefore, I would not be able to be hired there as a new substitute. However, once I’m in the system, I can keep teaching there. And since they frequently have substitute jobs that go unfilled, I wouldn’t be surprised if they once again declare a hardship and hire new substitutes such as me.

A quick Google search reveals that the following Minnesota school districts are currently hiring subsitutes and are willing to sign the certification so that you can get your license. So if you live in or near one of these districts, they would be the ideal starting point.

Please note that this is just a partial list of districts that currently publicize on their website that they’re willing to sign your application, and they are the ones I found with a quick Google search. There are undoubtedly many others. (Some districts might not want to publicize on their website that they’re experiencing a shortage, so a phone call might be productive.) To find these opportunities, check the district’s website, ask at your children’s school, or call the district. Many other Minnesota districts work with a firm called Teachers On Call, which handles the application process. Many of these districts will probably be willing to hire persons with a limited license as well.

Update: Since I originally wrote this post, my school district has switched to Teachers On Call, which now supplies subs for many districts in Minnesota and Wisconsin, including St. Paul, Roseville, and North Saint Paul. This means that I get a small bonus if they hire someone that I refer with the following link:

The Hiring Process

When you inquire, you will probably be asked to apply in person. And it’s quite likely that you will be hired on the spot, subject to obtaining your license. You’ll probably walk out with the required form signed by the superintendent, who is happy to learn that his or her chronic substitute shortage is one step closer to being solved. Chances are, the staff at the district will be able to assist you with the process of applying for your license. When you visit the district office, you should plan on being hired that day. Therefore, it’s a good idea to bring along your college transcript, as well as the ID documents (driver’s license and passport or social security card) to complete all of the required forms that day. (And don’t forget to bring your checkbook, since they’ll probably want a voided check to set you up for direct deposit.) There’s generally no need to provide a resume, although if you have one prepared, it’s probably a good idea to bring a copy along. When the license is approved, you’ll start getting jobs.

You will get little if any training. Most substitute teachers seem to be hired on a “sink or swim” basis. On your first day on the job, you will simply walk in, announce to the class that you’re their substitute for the day, and then make the best of the situation. You’ll probably be given some kind of handbook or guide explaining some district policies, but you will be given little if any advice on actually teaching.

You will be told the mechanics of how you get jobs. Before the internet came into existence, school districts employed a person often known as the “gatekeeper.” This person would report to work at 5:00 AM and wait for teachers to call in sick. When they did, he or she would start calling substitutes to fill the vacancy.

The job function of the “gatekeeper” has now been largely automated. Instead of a human calling you, you will go to a website and/or receive an automated telephone call. You will see all available positions and be able to select one. My district, and most others, use a system called AESOP. If you want to limit yourself to particular schools or grades, you have this option. But your license allows you to teach any grade level from preschool through adult, and you’ll be given the opportunity to take any available assignment. Since you don’t have to deal with a human being on the other end of the phone, it is very easy to be selective and take only the “good” jobs.

I currently have the telephone option turned off, and I get jobs strictly by logging in to the website. I usually have these jobs lined up in advance. If I were in need of daily work, I would set the alarm clock for 5:00 and wait for the phone to ring, safe in the knowledge that I would be working almost every day.

What the Work is Like

As a substitute teacher, there will be good days and bad days. Fortunately, however, the good days far outnumber the bad. And because you can pick your assignments, you never have to worry about going back to the bad classes! After a while of taking jobs, you will recognize which are the good schools, which are the good teachers, and which are the good classes. Armed with that knowledge, you can pick and choose and go back only to the good jobs.

Surprisingly, at first, it can be hard to predict which will be the good assignments and which will be the bad ones. I’ve taught at schools with extremely bad reputations, and often found those assignments to be the most rewarding experiences. On the other hand, I’ve also taken a few jobs at “good” schools where I don’t plan to go back. For this reason, the early days of your substitute experience will teach you a few lessons. But after you’ve figured out where the good jobs are, you’ll have days when you feel guilty about collecting a paycheck for such a fun assignment.

Because of my particular temperament, I prefer taking jobs in high school, junior high, and occasionally the upper elementary grades. I know that I wouldn’t be a particularly good kindergarten teacher, so I don’t take those jobs. Other substitutes are more suited to younger kids and would be horrified at the prospect of teaching high school students. The nice thing about subbing is that you can pick and choose.

One reason why I prefer high school and middle school is the fact that if I get a bad group of students, I know they’ll be gone in less than an hour. I can put up with just about anything for an hour. I rarely have miserable assignments, but it’s nice knowing that if I do, it’s of very short duration.

I have found that the principals, teachers, and all of the staff of the schools where I teach are genuinely happy to see me. There is indeed a shortage of substitute teachers, and there are times when they need one but don’t get one. When that happens, the other staff need to work harder. The regular teachers often need to use their prep hour to cover another class, or the principal or another administrator needs to step in. So when they see me, they’re happy to know that they don’t have to worry about the class that day.

Most times, the regular teacher leaves lesson plans. This is often an activity where I need to do little more than hand out the assignment and sit back as the students do the work. Many substitute teachers are happiest when they discover a lesson plan sitting on the desk. On the other hand, I tend to enjoy the situations where there is no lesson plan and I’m left to fend for myself. I consider myself a renaissance man, and I can always come up with something that ties in to what they’ve been studying, whether it’s math, English, social studies, science, or just about any other subject. It’s my chance to pontificate, and yes, I enjoy showing off to the students that I can do the algebra problem and that, in fact, yes, we do algebra in the “real world” on a regular basis.

The most common question I’m asked about substitute teaching is how well the students behave. Many adults recall their days as a student, and remember that when a substitute appeared in the room, the class erupted in chaos.

You will, indeed, experience chaotic situations from time to time as a substitute. Some students will believe that they can get away with anything with the regular teacher gone, and they will try to do so. However, by using a bit of common sense and displaying an aura of calm authority, most of these problems can be overcome quite easily. Occasionally, it’s necessary to kick some student out of the room and refer him to the assistant principal or whoever deals with behavioral issues. But this is actually quite rare, especially after students realize that you are willing to go to such extreme measures. Typically, students will do their job with a minimum of prodding.

I’m also frequently asked whether substitutes need to understand the subject matter that they’re supposedly teaching. The answer to this question is a resounding no. The expectation is that the substitute will have absolutely no understanding of the subject matter. If you maintain order for the day, you will be lauded for doing a great job. You’re not actually expected to impart any knowledge to the students.

Having said that, my favorite part of the job is actually imparting knowledge, or at the very least showing off to the students that I actually understand the material. So I take pride in explaining the causes of the Civil War on one day, and then applying the quadratic formula the next day. The students are duly impressed, the teacher is pleasantly surprised to discover that the students actually learned something, and I’m probably requested the next time that teacher is absent. But this is not the norm. Normally, if the classroom is still standing at the end of the day, then you have done your job as a substitute, and everyone is happy. So no, you do not need any particular knowledge of the subject matter in order to substitute teach. Even if you have no idea what the quadratic formula is, you’ll still do fine teaching math classes.

Even in the worst classes (which are, thankfully, rare), it is clear that most of the students want to learn something. It’s actually quite gratifying when a student thanks you at the end of class. The rewards can come at unexpected times. It’s not unusual to be teaching a history class and have a student ask if you can help with their math. Occasionally, you’ll see that the student finally “gets it” after struggling with something for quite a while. I’m not a better teacher than the regular teacher. But I might bring a different approach that works better for one particular student.

If I haven’t scared you off so far, then I encourage you to become a substitute teacher. The rules I’ve discussed here apply to Minnesota. Most other states allow substitute teachers without an education degree, although the qualifications will vary considerably from state to state. In fact, some require only a high school diploma. (Pay in such states, however, seems to be considerably lower than states requiring a four-year degree. One interesting possibility in such states is that college students can substitute while in college, although this is generally not possible in Minnesota.) Each state will have a different set of hoops to jump through. But most seem to have enough of a shortage of subs that they will assist you in every way possible as you jump through them.

You might get a small amount of training before your first job, but I’ve discovered that experience actually doing the job is much more valuable. If you want to do some reading before undertaking the job, you might find some of the following books and websites helpful:

BOOKS

WEBSITES

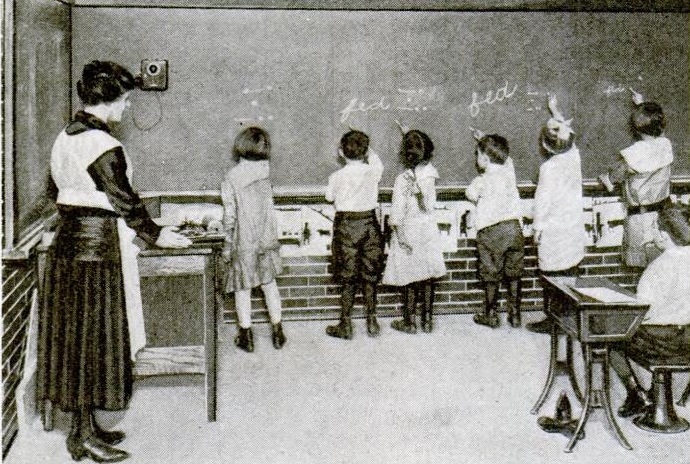

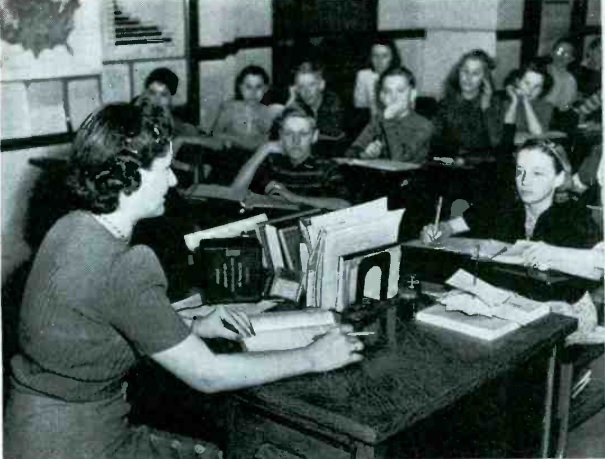

Seventy-five years ago, these high school students in Watertown, N.Y., were seen as a resource that would help the radio industry deal with wartime labor shortages. An article in the October 1942 issue of Radio Retailing explained the plan by which high school students could be trained to fill the gap. A group of servicemen in northern New York were planning to run an intensive course in radio servicing, open to high school seniors with a year of physics. The course was to be offered five nights per week, two hours each night, for ten weeks, and was taught by local servicemen who would both lecture in the classroom and offer periodic trips to the shop to tackle real receiver problems.

Seventy-five years ago, these high school students in Watertown, N.Y., were seen as a resource that would help the radio industry deal with wartime labor shortages. An article in the October 1942 issue of Radio Retailing explained the plan by which high school students could be trained to fill the gap. A group of servicemen in northern New York were planning to run an intensive course in radio servicing, open to high school seniors with a year of physics. The course was to be offered five nights per week, two hours each night, for ten weeks, and was taught by local servicemen who would both lecture in the classroom and offer periodic trips to the shop to tackle real receiver problems.