If it’s humanly possible, take your kids to see the eclipse on August 21!

National Park Service.

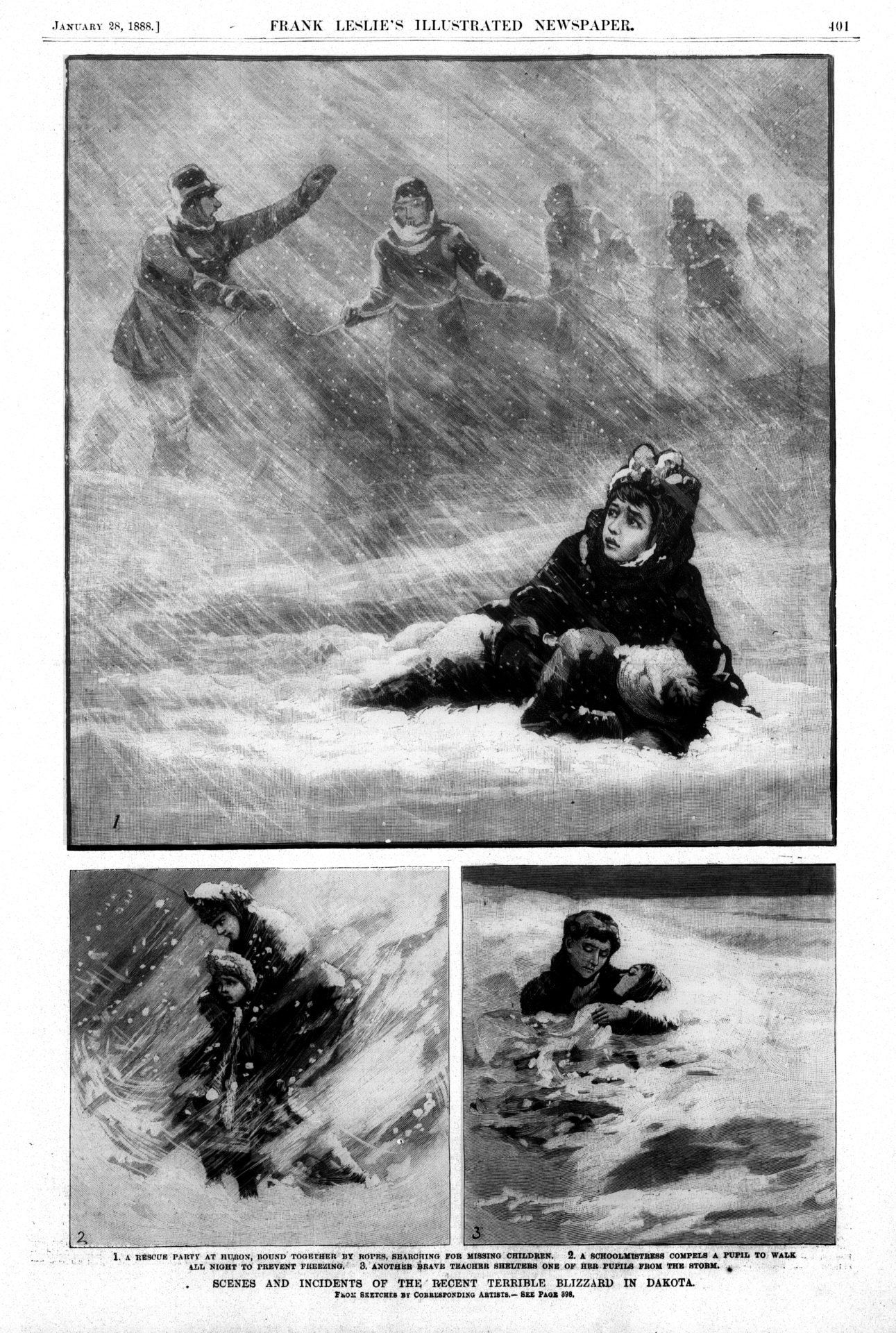

My first awareness of the concept of a solar eclipse came with the total eclipse of March 7, 1970. On that Saturday, the sun darkened in the Pacific, and the shadow of the moon raced over southern Mexico before entering the Gulf of Mexico.

Then, it hit the United States of America, with its shadow first hitting Florida, then Georgia, then the Carolinas and Virginia, then grazing Maryland before heading back out to sea, saying goodbye to the United States at Nantucket.

For those with Learjets, it then crossed Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, and the French island of Miquelon, before heading out to sea again into the North Atlantic.

Where I was in Minnesota, it only covered 47% of the sun at high noon. If nobody had told me about it, I wouldn’t have even noticed. It didn’t get dark outside, and no animals were confused. But that day, it was the biggest deal in the world. The moon contained fresh footprints of Americans who had walked on its surface less than a year before. Now that same moon was casting its shadow over me.

To me and my fellow third graders, it was presented as a big deal. And it was a big deal. If there had ever been any doubt about it, yes, the moon went around the earth, the earth went around the sun, and sometimes they got in the way of each other. Any third grader could see tangible proof.

In school, we had learned all about umbras and penumbras, and by the time the big day came, I was an expert on all things eclipse. With a shoebox, some foil, and a note card, I constructed myself a pinhole viewer. I figured that if a pinhole was good, then a giant hole would be even better. Fortunately, my mom corrected my error and got the viewer in good working order.

I pointed the box at the sun coming in the window, and sure enough, there was a little crescent shape of sunlight coming in through the round hole, plainly visible on the note card.

Perhaps I was a little disappointed at the tiny size of the image, but it didn’t matter. Right there in my shoebox was proof positive that the moon orbits the earth. I didn’t have to take anyone else’s word for it. The proof was right before my eyes.

We turned on the TV, and we saw the darkened skies and the amazed reactions of those who went outside to see it. I don’t remember too many details about the TV coverage. Mostly, I remember some poor confused rooster in Florida or Georgia crowing in the middle of the day.

When we got back to school the next Monday, the eclipse was the topic of conversation. We knew how the universe worked, because we had seen it with our own eyes. It was a big deal, and the kids remembered it.

In 1970, we were over a thousand miles away from the path of totality, and going to see it wasn’t really an option. But I envied those people and roosters on TV who got to see it in person.

Nine years later, another eclipse came to North America. On February 26, 1979, the eclipse started in the Pacific Northwest, darkened most of Montana, and grazed our neighboring state of North Dakota before making a spectacular show for humans and roosters alike in Winnipeg, Manitoba, tantalizingly close to Minnesota. I wanted to go to Winnipeg, but circumstances didn’t permit it. So I had to stay home and watch the 90% coverage. I had a telescope, complete with a solar filter that screwed to the eyepiece. In retrospect, that solar filter was horribly dangerous. The heat of the magnified rays of the sun could have cracked it, sending those same magnified rays right into my retina.

I got lucky, my retina survived, and I saw another eclipse. But it didn’t get dark outside. I didn’t hear any roosters. I was close, but I didn’t really see it. They said that it wouldn’t happen again until 2017, which sounded like an eternity to wait. But I vowed that I was going to go see it.

I’ve seen a couple other eclipses since then. I even drove to Springfield, Illinois, to get right in the middle of the path of the annular eclipse of May 10, 1994. My pinhole viewer revealed a tiny ring as the annular eclipse reached its peak. But it wasn’t dark, there were no roosters, and as far as I could tell, the citizens of Springfield didn’t even bother to come outside to see it, despite being right in the middle of the path.

By now, I was already convinced of the celestial mechanics. It was mildly interesting, but like the residents of Springfield apparently concluded, it wasn’t that big a deal.

The upcoming eclipse of August 21 is a big deal. It’s certainly a bigger deal than the one in 1994, because it’s actually going to get dark, and roosters will crow about it, just like they did in 1970 in Florida and 1979 in Winnipeg.

But it’s a much bigger deal than the one in 1970. In 1970, it wasn’t realistically possible for a family in Minnesota to go to Florida to witness it. That’s not true this time. Because the path of the eclipse so conveniently crosses the country from Pacific to Atlantic, the majority of Americans live within a one-day drive. For those of us in Minnesota, it means driving to Nebraska or Missouri. That is something that most families are capable of doing. You don’t need a Learjet. You don’t need to cross an international border. You don’t even need to drive to the other side of the country. All you need to do is drive to Nebraska.

Your kids never got to see men walking on the moon. They never even got a chance to see the Space Shuttle being launched. They’re vaguely aware of the International Space Station, but they don’t know the names of the two Americans and one Russian who are currently aboard. We know the names Armstrong, Aldrin, and Collins. But they don’t know the names Fisher, Yurchikhin, and Wilson. The wonder is seemingly gone.

On August 21, the wonder will be back. Those footprints are still up there on the moon, and that moon is going to cast a shadow over the Great Plains. Americans can’t go to the moon any more. But Americans–including your kids–can go see the shadow of that moon darken one of your neighboring states. You don’t need a Learjet; you don’t need to go to another country. You can probably get there on one tank of gas.

If you are in Minnesota or Iowa, I’ve already done the planning for you. You can drive to Nebraska on Sunday, stay in an inexpensive motel or camp that night, drive a few miles on Monday to see the eclipse, and get home Monday night. You can probably do it for a hundred bucks. If you live somewhere else, then you’ll have to do the planning yourself. But wherever you are in the 48 states, you are probably within one day’s drive. You should go.

If you go, your kids will see it get dark at noon, and if there are any roosters around, they’ll be able to hear them. If you go, the flat earthers will never stand a chance of misleading your kids. Your kids will know how the universe works, because they will have seen it with their own eyes. The wonder will be back.

In Minnesota, school is not yet in session, so your kids won’t even miss school. You’ll probably need to take a day off from work, but don’t you think it’s worth it?

If you live somewhere where school is in session, then it would be nice to think that the schools will take care of educating your children. But don’t count on it. During a recent eclipse in Britain, some schools kept the kids inside, with the blinds closed, during the eclipse. The kids watched it on TV, and apparently have to take the TV’s word for it that the earth isn’t flat.

Some American schools seem to be taking the same approach. Take, for example, the case of Shawnee Mission, Kansas, located only about 10 miles from the path of totality. School will be in session on August 21. If I were in charge, there would only be one logical thing to do. If I’m an educator, then my duty is to educate the kids. And there is only one logical way to do that–put the kids on a school bus and drive them the 10 miles so that they can see the sky go dark and hear that confused rooster crow. But that’s not what they’re doing. They’ll close the curtains and watch it on the internet. “Some schools even plan to reschedule outdoor recess to avoid being outside during the eclipse.” The kids will just have to take the internet’s word for it that the earth isn’t flat. They won’t be allowed to see for themselves.

Fortunately, some schools deserve praise for proactively making sure that their students get to experience the total eclipse. For example, the Parkway School District near St. Louis discovered that one of its schools was outside the path of totality. So they made the wise decision to bus those kids to one of the neighboring schools that will experience totality.

One school that deserves particular praise is Lewis Central Middle School in Council Bluffs, Iowa. Even though school won’t even be in session yet, the science teachers there took it upon themselves to organize a summer field trip a hundred miles away to Beatrice, Nebraska, to view the eclipse.

Unfortunately, however, these educators who actually decide to educate the kids seem to be the exceptions. If school is in session, don’t take it for granted that the teachers will be proactive about allowing kids to have a sense of wonder about the universe. Like in Britain or in Shawnee Mission, Kansas, there’s a distinct possibility that your kids will be locked in a room with the blinds closed where they’ll watch it on the internet. And that would be a shame. Your kids deserve the chance to see for themselves that the earth isn’t flat. They shouldn’t have to take the internet’s word for it.

If you decide to go, and you should: