The December 1970 issue of Popular Electronics provides some good advice to anyone seeking to learn about any subject. They were talking about electronics, but the same general advice applies to any field.

The December 1970 issue of Popular Electronics provides some good advice to anyone seeking to learn about any subject. They were talking about electronics, but the same general advice applies to any field.

The magazine began by noting that money spent on a formal education is a generally wise investment. But in many cases, the student might not want to commit to a formal education. Among other things, formal education normally costs money.

But even though it has built-in disadvantages, a course of informal “go-it-alone” self study can provide a firm understanding, at a minimal investment. In 1970, the monetary investment came to $18.55. But in the internet age, that cost is essentially zero.

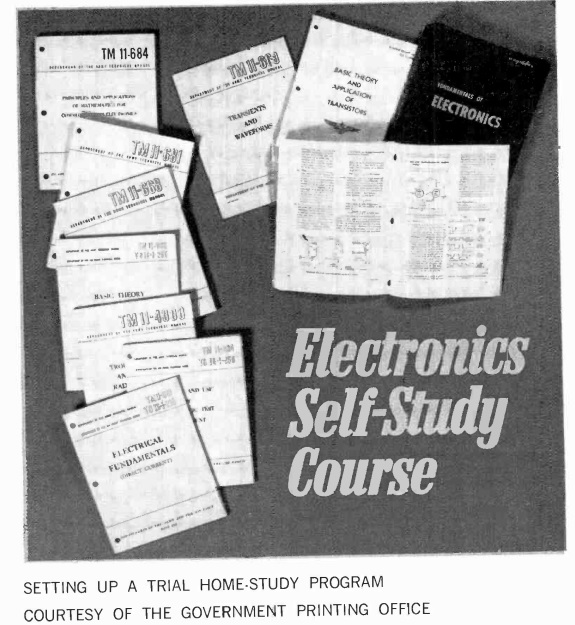

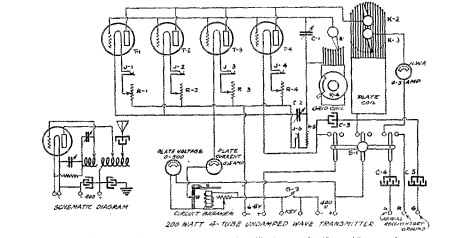

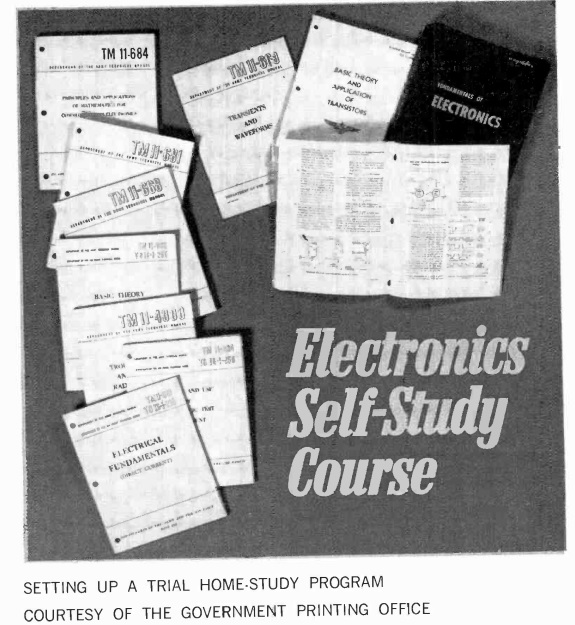

The magazine warned of simply buying a book and hoping that it would provide the correct study material, since it might not provide a broad enough scope. But the magazine noted that there were inexpensive books that were well designed for the purpose, namely, training manuals used by the military, and for sale at a nominal cost by the Government Printing Office. It went on to list those books recommended for a basic course in electronics, and the total cost was only $18.55.

Today, most of those same books are available at no cost on the internet. Specifically, here they are, with links to Google Books or other sources:

Of course, these texts are all now more than a half century old. But the basic theory is unchanged, and that course of study would provide an excellent background, even though the student might learn a bit of archaic material in the process. With minimal research, the interested student could update the course materials and include modern texts in electronics–or modern texts in any other subjects.

Today, it is quite possible to get a good university education and spend hundreds of thousands of dollars in the process. If you do this, two things will happen. First, you will presumably become a smarter person, because you have learned the material that was taught. And you will also get a handsome piece of paper from a prestigious institution attesting to the fact that you have learned the material. That piece of paper is very good to have. Indeed, if you want to do some things, such as perform surgery, then having that piece of paper is absolutely required.

But you can gain all of the knowledge without the piece of paper. Even though I have an advanced degree, I’ve come to the conclusion that for many, the piece of paper isn’t particularly valuable, even though the knowledge is.

If you pay tuition at a university, you will take courses, and during those courses, you will be given a list of books to read, and you will attend lectures explaining those texts. The books have always been available for purchase, or you can read them at the library. And in many cases, the lecture is available online for anyone to view, whether or not they have paid tuition.

If you pay tuition, you also have the privilege of showing up at the professor’s office hours and asking questions. But in my experience, students never do that.

In short, my advice to many students is that perhaps paying tuition isn’t really in your best interest any more. You can gain the knowledge for free. At that point, you’ll need to figure out a substitute for the piece of paper attesting to your knowledge.

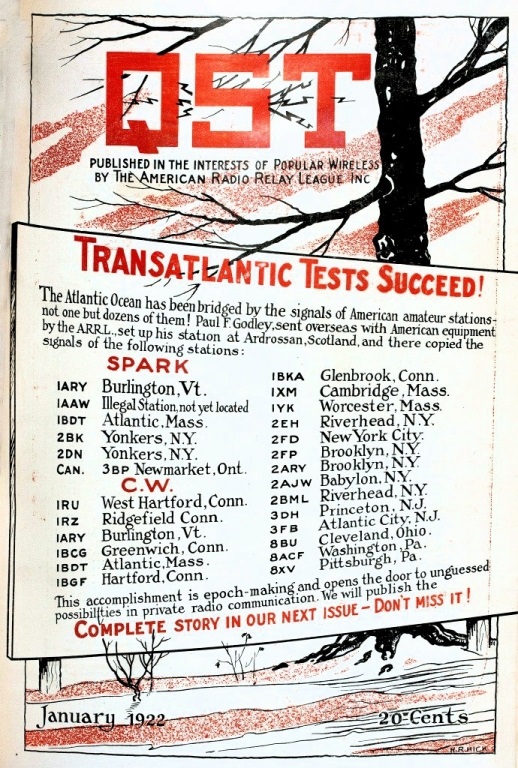

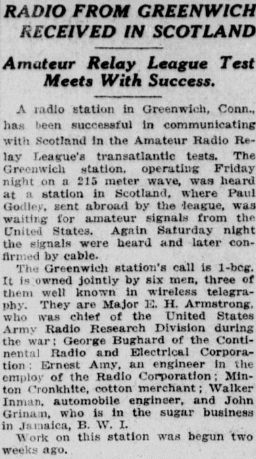

In 1970, one suggestion that Popular Electronics made was to obtain your FCC Radiotelephone License, preferably the prestigious first class license. That option is still available, although it’s less prestigious, and the license is now called the General Radiotelphone Operator License (GROL). In fact, I’m the author of a study guide to earn that license.

The GROL is still the ticket to a handful of jobs in electronics, but in many cases, it’s unknown to employers. But there are probably other methods of proving your bona fides. And before long, other people like me, who have advanced degrees and a stake in higher education, are also going to start coming to the realization that maybe that fancy piece of paper is overpriced. And eventually, someone is going to come up with a less expensive alternative piece of paper. In many industries, that piece of paper probably already exists.

In short, my advice is to consider whether self-study might work for you. If done right, you can learn almost as much, or as much, as students undergoing formal education. And if you’re smart enough to do that, perhaps you are also smart enough to figure out a way to prove it, even without that handsome, but expensive, piece of paper.

Some links on this site are affiliate links, meaning that this site earns a small commission if you make a purchase after clicking on the link.

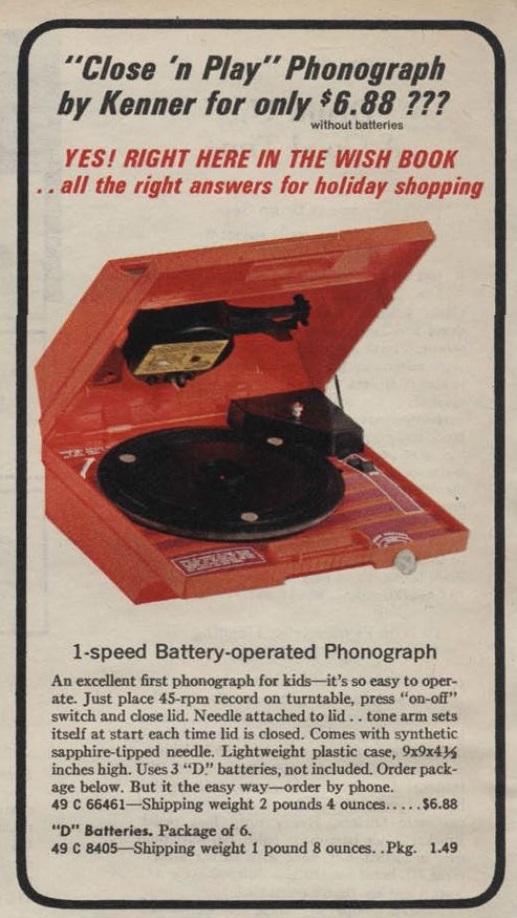

It was probably 1971, plus or minus a year or so, that Santa Claus brought me my very own record player. We had at least two phonographs around the house, and at least one of them was used mostly by me. But it wasn’t mine, and thanks to the Kenner Close ‘n Play phonograph, any kid could own one. And the parents’ (and/or Santa Claus) would only be out $6.88, plus the cost of three D cell batteries (According to this inflation calculator, that works out to about $47 in 2021 dollars.

It was probably 1971, plus or minus a year or so, that Santa Claus brought me my very own record player. We had at least two phonographs around the house, and at least one of them was used mostly by me. But it wasn’t mine, and thanks to the Kenner Close ‘n Play phonograph, any kid could own one. And the parents’ (and/or Santa Claus) would only be out $6.88, plus the cost of three D cell batteries (According to this inflation calculator, that works out to about $47 in 2021 dollars.