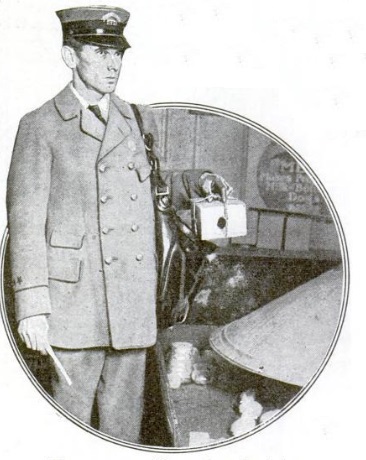

The cover of Radio Craft magazine 75 years ago this month, October 1944, showed an artist’s conception of the apparatus used for on-the-spot recordings of the D-Day invasion. Those broadcasts were made by Blue Network correspondent George Hix, whose reports were part of the pool coverage and heard on the other networks. You can listen to the reports at the video below.

The cover of Radio Craft magazine 75 years ago this month, October 1944, showed an artist’s conception of the apparatus used for on-the-spot recordings of the D-Day invasion. Those broadcasts were made by Blue Network correspondent George Hix, whose reports were part of the pool coverage and heard on the other networks. You can listen to the reports at the video below.

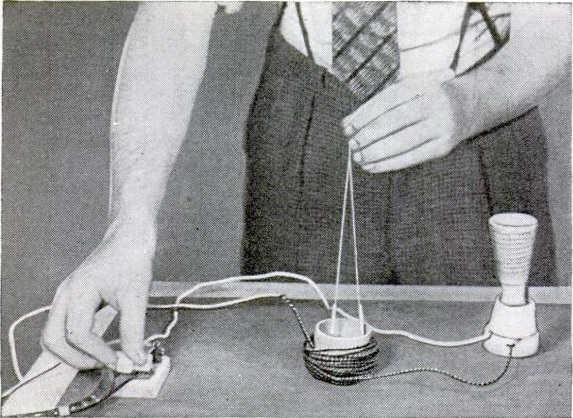

The equipment being used was a Recordgraph manufactured by Amertype. We previously described that equipment. It was a technology that was short lived, since it was soon replaced by magnetic recording. It recorded grooves on a 50 foot roll of film, with a total of 12,000 feet of sound track (in other words, 240 tracks on a strip of 35 mm film). The process is identical to a phonograph recording, but with a strip instead of a disc. The system allowed five hours of speech per roll. As you can hear from the recording below, the sound quality was quite good.

The magazine noted that the Navy considered that the device’s primary use would be production of a real-time log of a battle, although the ability to record a reporter’s voice was an important secondary use.