Fern Sunde.

We previously told the story of Fern Sunde, the Canadian-born radio operator who served aboard a Norwegian freighter during World War II. While Ms. Sunde was the most famous, we noted that 23 other women served in the role of radio officer in the Norwegian merchant marine.

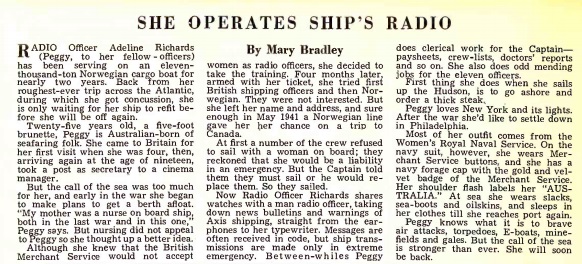

The July 1943 issue of Radio Mirror contains the story of another woman, Adline “Peggy” Richards, born in Australia in about 1918, who also served as radio officer aboard a Norwegian freighter. Here is that article in its entirety.

SHE OPERATES SHIP’S RADIO

By Mary Bradley

Radio Officer Adeline Richards (Peggy, to her fellow officers) has been serving on an eleven-thousand-ton Norwegian cargo boat for nearly two years. Back from her roughest-ever trip across the Atlantic, during which she got concussion, she is only waiting for her ship to refit before she will be off again.

Twenty-five years old, a five-foot brunette, Peggy is Australian-born of seafaring folk. She came to Britain for her first visit when she was four, then, arriving again at the age of nineteen, took a post as secretary to a cinema manager.

But the call of the sea was too much for her, and early in the war she began to make plans to get a berth afloat. “My mother was a nurse on board ship, both in the last war and in this one,” Peggy says. But nursing did not appeal to Peggy so she thought up a better idea.

Although she knew that the British Merchant Service would not accept women as radio officers, she decided to take the training. Four months later, armed with her ticket, she tried first British shipping officers and then Norwegian. They were not interested. But she left her name and address, and sure enough in May 1941 a Norwegian line gave her her chance on a trip to Canada.

At first a number of the crew refused to sail with a woman on board; they reckoned that she would be a liability in an emergency. But the Captain told them they must sail or he would replace them. So they sailed.

Now Radio Officer Richards shares watches with a man radio officer, taking down news bulletins and warnings of Axis shipping, straight from the earphones to her typewriter. Messages are often received in code, but ship transmissions are made only in extreme emergency. Between-whiles Peggy does clerical work for the Captain–paysheets, crew-lists, doctors’ reports and so on. She also does odd mending jobs for the eleven officers.

First thing she does when she sails up the Hudson, is to go ashore and order a thick steak.

Peggy loves New York and its lights. After the war she’d like to settle down in Philadelphia.

Most of her outfit comes from the Women’s Royal Naval Service. On the navy suit, however, she wears Merchant Service buttons, and she has a navy forage cap with the gold and velvet badge of the Merchant Service. Her shoulder flash labels her “AUSTRALIA.” At sea she wears slacks, sea-boots and oilskins, and sleeps in her clothes till she reaches port again.

Peggy knows what it is to brave air attacks, torpedoes, E-boats, minefields and gales. But the call of the sea is stronger than ever. She will soon be back.

I’ve been unable to find any other information about Ms. Richards. If anyone, perhaps a relative, knows more about this radio pioneer, I would love to hear from you. I can be contacted at clem.law@usa.net.

Shown here in the July 1943 issue of Radio Retailing Today are students in one of the successful radio courses offered by Sewanhaka Central High School in Floral Park, Long Island, New York.

Shown here in the July 1943 issue of Radio Retailing Today are students in one of the successful radio courses offered by Sewanhaka Central High School in Floral Park, Long Island, New York.