On this day 90 years ago, May 21, 1927, Charles Lindbergh landed in Paris, completing the first ever solo flight across the Atlantic.

See also: Fall of Paris, 1940

On this day 90 years ago, May 21, 1927, Charles Lindbergh landed in Paris, completing the first ever solo flight across the Atlantic.

See also: Fall of Paris, 1940

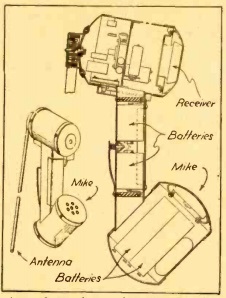

Seventy-five years ago this month, the May 1942 issue of Radio Craft featured on its cover this handheld radio telephone weighing only four pounds, which the magazine noted was not much larger than the handset of a “French” telephone. The set was the product of the Weltronic Corporation, which was the assignee of the patent, U.S. Patent 2276933, with a pre-Pearl Harbor application date of October 1, 1941, and an issue date of March 17, 1942.

Seventy-five years ago this month, the May 1942 issue of Radio Craft featured on its cover this handheld radio telephone weighing only four pounds, which the magazine noted was not much larger than the handset of a “French” telephone. The set was the product of the Weltronic Corporation, which was the assignee of the patent, U.S. Patent 2276933, with a pre-Pearl Harbor application date of October 1, 1941, and an issue date of March 17, 1942.

The magazine noted that the set had a range of about a mile, and could operate on any frequency between 112-300 MHz. The diagram below reveals that the set appears to be one tube functioning as an oscillator and superregenerative detector, with the other tube serving as AF amplifier to drive the headphone on receiver, and as modulator on transmit.

The magazine noted that the set had a range of about a mile, and could operate on any frequency between 112-300 MHz. The diagram below reveals that the set appears to be one tube functioning as an oscillator and superregenerative detector, with the other tube serving as AF amplifier to drive the headphone on receiver, and as modulator on transmit.

Commercially available batteries were said to allow continuous operation for eight hours, or about a week to a month in normal service. The article noted that the set was being made available to governmental agencies.

The cover photo shows the unit in use by a guard around a defense plant.

The article puts quotation marks around the word “transceiver,” since such a combined unit would have been unfamiliar to many readers.

On this day one hundred years ago, May 18, 1917, Congress passed the Selective Service Act of 1917, authorizing the military draft, now that the nation was at war.

Unlike the draft for the Civil War, the act specifically prohibited the hiring of substitutes:

No person liable to military service shall hereafter be permitted or allowed to furnish a substitute for such service; nor shall any substitute be received, enlisted, or enrolled in the military service of the United States; and no such person shall be permitted to escape such service or to be discharged therefrom prior to the expiration of his term of service by the payment of money or any other valuable thing whatsoever as consideration his release from military service or liability there to.

The first registration under the act, for men age 21-31, was set for June 5, 1917. 18 year olds were set to be registered in 1918.

In 1918, the U.S. Supreme Court held the Act constitutional.

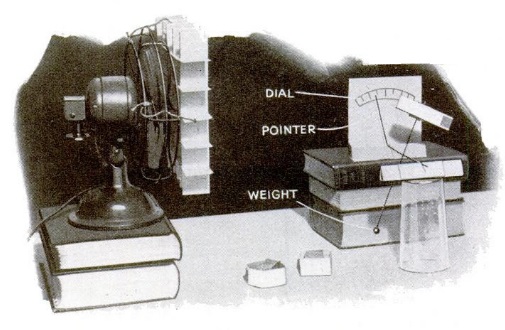

If Junior just remembered that the Science Fair project is due tomorrow, and he hasn’t even started, there’s no need to panic. The little project shown here can easily be whipped up in an evening, and the teacher will be none the wiser about your haste. He or she will assume that the little scientist has been working on it for weeks.

If Junior just remembered that the Science Fair project is due tomorrow, and he hasn’t even started, there’s no need to panic. The little project shown here can easily be whipped up in an evening, and the teacher will be none the wiser about your haste. He or she will assume that the little scientist has been working on it for weeks.

While Mom and Dad race to the dollar store before it closes to buy the poster board and markers, Junior can start building this instrument for measuring wind resistance for objects of various sizes. Unless someone sticks their fingers into the moving fan blades, this experiment should be completely safe. It appeared 80 years ago this month in the May 1937 issue of Popular Science.

Of course, the teacher expects the students to come up with things like a hypothesis, which should be pretty easy. All Junior needs to do is come up with a sentence such as “a ______ shaped object has more wind resistance than a ______ shaped object.” The blanks can be filled in with whatever objects are easier to construct, for example, a cube and a sphere.

The instrument shown here is pretty self-explanatory. The object being tested is mounted on top of a rigid wire, with a counterweight at the bottom. To make it look fancy, you can make the pointer and scale. Then, you balance the wire and blow a fan at it. The object that deflects the furthest has the greater wind resistance.

As can be seen here, the fan has an “egg box partition” in front of it to straighten out the air currents. Apparently, in 1937, most households had egg boxes lying around with cardboard partitions. A modern egg carton probably won’t work, but Junior can retrieve some cardboard from the recycling bin and simply make a grate consisting of square openings.

When you get home with the poster board, Junior can copy down some interesting facts from the Wikipedia article about drag, and the result will probably be a blue ribbon.

Shea performing in 1957. YouTube image.

If you’re like me, you probably assumed that the hymn How Great Thou Art has always been a part of the American religious music scene. However, it is actually relatively new, being first popularized only sixty years ago, in 1957. It was performed for the first time by George Beverly Shea at Billy Graham‘s Madison Square Garden Crusade, which began on this night 60 years ago, May 15, 1957. The crusade lasted until September 1, and during its run, more than two million persons attended to hear Graham preach and Shea sing. Over 56,000 reportedly responded to the message by making a decision for Christ.

In the video below, Cliff Barrows describes it in his introduction as “a new hymn to American audiences.” The hymn was not exactly new when Shea brought it to American audiences. The tune was a traditional Swedish melody. The Swedish lyrics, “O Store Gud” were penned in 1885 by Carl Boberg, who was inspired while walking home from church listening to church bells. A sudden storm was followed by a similarly sudden calm. According to Boberg, the words were a paraphrase of Psalm 8:

Lord, our Lord,

how majestic is your name in all the earth!

You have set your glory

in the heavens.

The first translation of the hymn was into Russian in 1912, “Velikiy Bog” (Великий Бог – Great God) by Ivan S. Prokhanov. It was published in a Russian Protestant hymnal in 1927.

The first English translation came in 1925 by E. Gustav Johnson, who made a literal translation of the Swedish lyrics published in the Covenant Hymnal as “O Mighty God.” Those words remained as late as the 1973 edition:

O mighty God, when I behold the wonder

Of nature’s beauty, wrought by words of thine,

And how thou leadest all from realms up yonder,

Sustaining earthly life with love benign,With rapture filled, my soul thy name would laud,

O mighty God! O mighty God!

Credit for the now familiar English lyrics goes largely to British Methodist missionary Stuart Wesley Keene Hine, who heard the hymn sung in Ukraine in 1931. He did a paraphrase of the Russian translation, which includes most of the familiar lyrics, as well as the title, “How Great Thou Art.”

Hine finalized the lyrics in 1949, and he performed it for the first time at a convention in New York in 1951. It was first published in 1956, in the collection “Eastern Melodies & Hymns of Other Lands.”

The hymn soared in popularity after Shea’s 1957 performances at the Madison Square Garden Crusade. It’s unclear whether the hymn was performed on the first night of the crusade 60 years ago tonight, but it was performed at most of the services.

For comparison, here is the Swedish version:

And the Russian:

Forty years ago, electronic calculators had been on the market for a few years, and they were starting to get smaller and cheaper. Those who wanted the smallest calculator might have given some consideration to this kit advertised in the May-June 1977 issue of Elementary Electronics.

Forty years ago, electronic calculators had been on the market for a few years, and they were starting to get smaller and cheaper. Those who wanted the smallest calculator might have given some consideration to this kit advertised in the May-June 1977 issue of Elementary Electronics.

Offered by Sinclair (the same people who put out one of the first inexpensive home computers), the wrist calculator sold in kit form for only $19.95. The ad noted that a pocket calculator was good, but goes only where your pocket goes. “Take your jacket off, and you’re lost.”

The wrist calculator, on the other hand, was always with you whenever you had calculating needs.

The calculator featured an eight digit display, and to squeeze in the keyboard, it used ten keys “do the work of 27.” The digits 1-0 were marked on the keys. But on the side of the case was a three position switch. In the center position, the keys entered the numbers. But when set to the left and right, the keys became function keys. In addition to the normal four functions, the calculator boasted percentage, square root, reciprocal, and square. It also had a five-function memory.

A set of readily available hearing aid batteries were said to give weeks of service. All parts were included, and assembly required only a fine-point soldering iron.

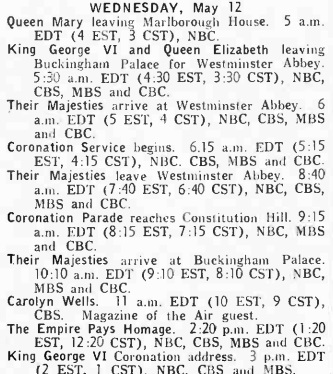

The Coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth (the mother and father of the current Monarch) took place on this date 80 years ago today, on May 12, 1937.

King George V had died on January 20, 1936, at which time Edward VIII assumed the throne. Shortly thereafter, he caused a constitutional crisis after announcing his plans to marry American divorcee Wallis Simpson. The crisis was resolved by his abdication on December 11, 1936, at which time George VI assumed the throne.

Edward’s coronation was originally scheduled for May 12, 1937, and the event went on as scheduled, with George rather than Edward being crowned.

The event was broadcast live by radio in America. Radio Guide for the week ending May 15, 1937 predicted that the event would be “without doubt, radio’s biggest show–the ‘crowning event’ in the twenty-odd years of radio broadcasting’s existence.” The magazine reported that there would be a battery of microphones in place to bring the scene to listeners all over the world.” NBC and CBS planned six hours of continuous coverage.

The event was broadcast live by radio in America. Radio Guide for the week ending May 15, 1937 predicted that the event would be “without doubt, radio’s biggest show–the ‘crowning event’ in the twenty-odd years of radio broadcasting’s existence.” The magazine reported that there would be a battery of microphones in place to bring the scene to listeners all over the world.” NBC and CBS planned six hours of continuous coverage.

This day 75 years ago marks the beginning of a little remembered part of the Second World War, the Battle of the St. Lawrence, which brought fighting to North America. In the early morning hours of May 12, 1942, a German U-boat sunk the freighter Nicoya.

While the Kriegsmarine had no formal plans to attack shipping in the St. Lawrence River and Gulf of St. Lawrence, the German submarine U-553 had been operating off the Canadian coast and made its way into the Gulf of St. Lawrence. On May 12, it torpedoed and sank the Nicoya at the mouth of the St. Lawrence River. Between 1942 and 1944, a total of 23 ships, including four Canadian warships, all well within the territorial limits of Canada.

Sources

This ad for a humble toaster appeared 70 years ago in the May 12, 1947, issue of Life magazine.

This ad for a humble toaster appeared 70 years ago in the May 12, 1947, issue of Life magazine.

Made in the USA, in a factory owned by General Electric, the toaster is undoubtedly well made. It’s undoubtedly heavy, reliable, and probably made excellent toast. The accompanying text touted the fact that it was adjustable, and the toast would be done exactly how you wanted it, light, medium, or dark. The snap-in crumb tray allowed it to be cleaned in ten seconds. And it even had another feature not found in modern toasters, the ability to have the toast either pop up when finished, or stay inside to keep warm until it was needed.

In the unlikely event that it broke, there were shops where you could take your toaster to be repaired.

In short, it was probably better than a toaster you would buy today, and it’s easy to pine for that simpler time when toasters were better. Until you look at the price.

This simple toaster cost $17.75. To put it another way, you could buy it with eighteen silver dollars, and those silver dollars would set you back exactly $18 in paper currency. Those same eighteen silver dollars today would cost you over $300.

So yes, the toaster 70 years ago was better than the typical toaster you would buy today. Today, you would probably buy a model similar to the ones shown below.

Yes, the 1947 version was probably better. But it was also a lot more expensive.

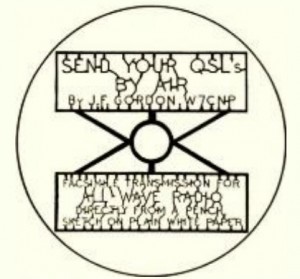

Eighty years ago this month, the May 1937 issue of All Wave Radio magazine carried a description by J.F. Gordon, W7CNP, of his method of sending facsimile by radio. The received image is shown above. While the system was quite simple in theory, it does appear to be quite labor intensive.

The received image, shown above, is reproduced on photographic film. The original transmitted image, drawn in pencil, is shown at the left. Since the entire image is drawn in pencil, it is conductive, and can be scanned by a conductive stylus. There needs to be continuity between all points on the image, and for this reason, the letters are all linked by a pencil line. Before transmission, these lines are covered up with coil dope or another insulating substance.

The received image, shown above, is reproduced on photographic film. The original transmitted image, drawn in pencil, is shown at the left. Since the entire image is drawn in pencil, it is conductive, and can be scanned by a conductive stylus. There needs to be continuity between all points on the image, and for this reason, the letters are all linked by a pencil line. Before transmission, these lines are covered up with coil dope or another insulating substance.

The image is then scanned on a normal phonograph turntable, powered by a synchronous motor to keep the speed at both ends of the circuit exactly the same. The image is scanned by a stylus riding on a threaded rod geared to the turntable motor.

An audio signal is sent through the circuit from the pencil lead to the stylus, and this signal is used to modulate the transmitter.

At the receiving side, an identical turntable is employed. For receiving, the stylus is replaced by a neon lamp. A piece of photographic film is placed on the turntable, which of course needs to be in a darkened enclosure. A second neon lamp is placed outside the box to make sure the system is receiving properly.

The neon lamp is driven by the receiver audio. Assuming everything is working properly, when the film is developed, it sould reveal a negative image of the original pencil disk.