For the aspiring mad scientist, young or old, the November 1945 issue of Popular Science shows how to make several homemade microphones. If you’re a student looking for a science fair project, then building your own microphone is probably going to impress the teacher more than a homemade volcano. While other kids might even put together electronic projects, it’s unlikely that very many of them will put together individual electronic components. And since most people think of microphones as sensitive and complicated instruments, you’ll probably be the only one to think of it. You’ll discover that most of them are quite simple to construct, although there’s no need for you to share that little secret with the judges.

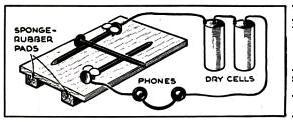

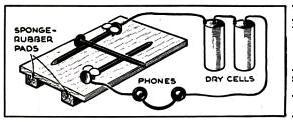

The first design, shown here and in the photograph at the top of the page, is simplicity itself. It consists of little more than three nails, one resting precariously on top of the other two. When struck by sound waves, the top nail vibrates, causing a slight change in resistance.

The first design, shown here and in the photograph at the top of the page, is simplicity itself. It consists of little more than three nails, one resting precariously on top of the other two. When struck by sound waves, the top nail vibrates, causing a slight change in resistance.

The second design, shown here, is only slightly more sophisticated. It is a carbon button microphone, and consists of carbon granules in a small container, such as the cap of a ketchup bottle. As sound strikes the granules, the resistance changes. This setup requires a slightly higher voltage, but will give you considerably more audio output. The carbon granules can be obtained by cracking open a carbon-zinc battery (the cheap kind), removing the carbon rod in the middle, and crushing it up. A double-button design is also shown for the advanced student.

The second design, shown here, is only slightly more sophisticated. It is a carbon button microphone, and consists of carbon granules in a small container, such as the cap of a ketchup bottle. As sound strikes the granules, the resistance changes. This setup requires a slightly higher voltage, but will give you considerably more audio output. The carbon granules can be obtained by cracking open a carbon-zinc battery (the cheap kind), removing the carbon rod in the middle, and crushing it up. A double-button design is also shown for the advanced student.

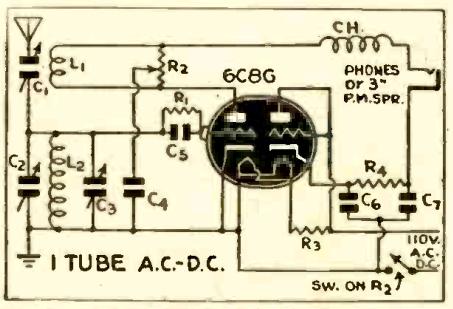

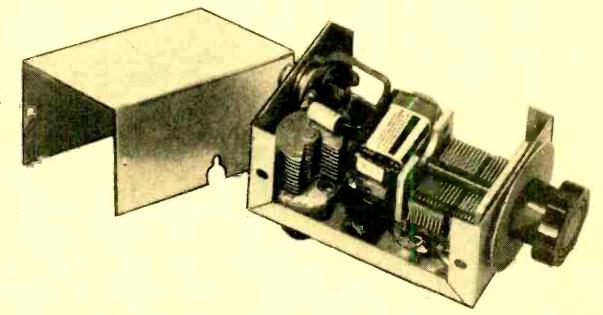

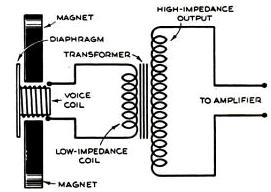

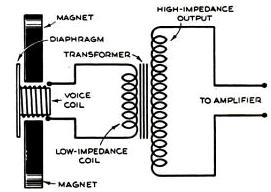

A homemade dynamic microphone is shown here. It consists of a coil of wire mounted between two magnets. When the coil moves as a result of sound, the microphone becomes a tiny electric generator producing an AC current in time with the sound. Unlike the earlier designs, which simply varied the resistance, this one requires an amplifier to amplify the tiny current generated. In 1945, this probably posed a bit of a problem. But today, you can easily connect it to a cheap audio amplifier such as this one

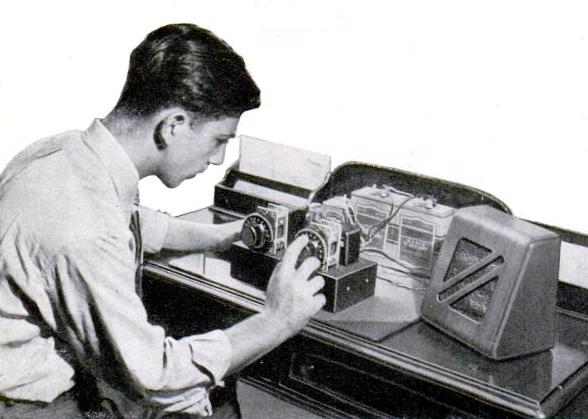

A homemade dynamic microphone is shown here. It consists of a coil of wire mounted between two magnets. When the coil moves as a result of sound, the microphone becomes a tiny electric generator producing an AC current in time with the sound. Unlike the earlier designs, which simply varied the resistance, this one requires an amplifier to amplify the tiny current generated. In 1945, this probably posed a bit of a problem. But today, you can easily connect it to a cheap audio amplifier such as this one and get plenty of audio to impress the judges. You can also simply plug the microphone into the microphone input of a computer. Another variation of the dynamic mike, also described in the article, is the ribbon mike, which substitutes a thin ribbon of foil for the diaphragm.

and get plenty of audio to impress the judges. You can also simply plug the microphone into the microphone input of a computer. Another variation of the dynamic mike, also described in the article, is the ribbon mike, which substitutes a thin ribbon of foil for the diaphragm.

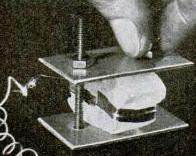

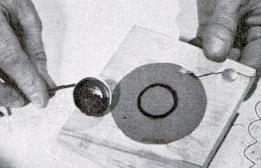

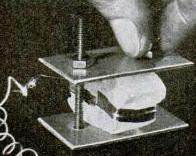

The final, and most advanced, microphone described in the article is shown here. This is the piezoelectric or crystal microphone, which your teacher would probably tell you is impossible to make at home. But your teacher is wrong, as shown by this 70 year old article. You simply grow yourself a suitable piezoelectric crystal and arrange it as shown here. While it might sound intimidating to grow a crystal, this is actually the same thing your less advanced peers are doing by making rock candy as their science fair entry. Instead of using sugar to make the crystal, you use Rochelle Salt (potassium sodium tartate). Your chemistry teacher probably has a dusty bottle in the lab. If not, you can simply buy some on Amazon

The final, and most advanced, microphone described in the article is shown here. This is the piezoelectric or crystal microphone, which your teacher would probably tell you is impossible to make at home. But your teacher is wrong, as shown by this 70 year old article. You simply grow yourself a suitable piezoelectric crystal and arrange it as shown here. While it might sound intimidating to grow a crystal, this is actually the same thing your less advanced peers are doing by making rock candy as their science fair entry. Instead of using sugar to make the crystal, you use Rochelle Salt (potassium sodium tartate). Your chemistry teacher probably has a dusty bottle in the lab. If not, you can simply buy some on Amazon . Like the dynamic microphone, this one is hooked up to an audio amplifier.

. Like the dynamic microphone, this one is hooked up to an audio amplifier.

If you’re a student, your teacher is probably tired of homemade volcanoes, potato clocks, and other scientific curiosities that he or she has seen a hundred times before. Your homemade microphone(s) will be most impressive. And even if your school days are behind you, making these simple microphones will be quite rewarding.

Click Here For Today’s Ripley’s Believe It Or Not Cartoon

![]()