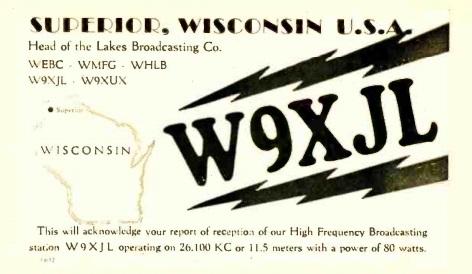

W9XJL 1938 QSL card, All Wave Radio, Feb. 1938. A color image of the card can be found at this link.,

You probably didn’t know that Superior, Wisconsin, was once the home of a shortwave broadcast station. Station W9XJL was an experimental station licensed to Head of Lakes Broadcasting Company. It originally operated with 80 watts on 26.10 MHz, and later increased its power to 250 watts. The January 1940 issue of Radio & Television magazine carries the following report:

W9XJL, 26.10 mc, Superior, Wis., is now using a full 250 watts from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. daily. Much can be said for the fine quality and consistency this station has shown in the last three years and for its excellent verification policy. Our observers in Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Jersey, Florida, Arizona, California and Washington all report an R9 signal whenever the band opens.

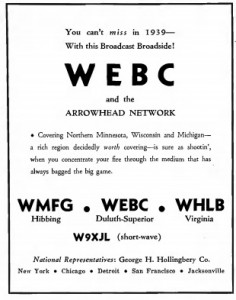

WEBC-W9XJL advertisement, 1939 Broadcasting Yearbook.

W9XJL simulcasted Duluth-Superior station WEBC on the Apex band, which existed from 1934 to 1940. The 11 meter band (25-27 MHz) was allocated internationally for broadcasting, but largely unused outside of the U.S. Apex stations. In Minnesota, both WCCO and WTCN had licenses to broadcast on the Apex band, as W9XHW and W9XTC respectively. (A portion of the band, 25.6-26.1 MHz, is still allocated for international broadcasting, but rarely used.) Some sources incorrectly describe W9XJL as an FM station, but it actually used amplitude modulation, although the Apex stations generally used a wider bandwidth than on the standard broadcast band, thus allowing for a more “high fidelity” audio signal.

W9XJL transmitted from 40th and Tower Avenue in Superior. The program was generally the same as WEBC, with an announcer at the transmitter location breaking in to give the station identification. One interesting use of the station was reported in 1937 as the relay of personal messages to and from persons wintering on Isle Royale. Station WSHC was licensed to Isle Royale.

W9XJL did receive reception reports from around the world. As noted above, it had a good reputation for QSL’ing.

References

- WEBC Timeline

- Grant of Construction Permit, Sept. 22, 1936, Broadcasting Magazine, Oct. 1, 1936, p. 76

- Broadcasting, Feb. 1, 1937, p. 65

Click Here For Today’s Ripley’s Believe It Or Not Cartoon

![]()