If Junior wants to take home the blue ribbon at the next science fair, this project will almost certainly provide it. When Junior announces to the science teacher that he or she is going to build an anemometer (an instrument for measuring wind speed) with no moving parts, the teacher will be mystified, and will wonder whether it is even possible. But when they see the completed device in action, they will be astonished at its simplicity.

If Junior wants to take home the blue ribbon at the next science fair, this project will almost certainly provide it. When Junior announces to the science teacher that he or she is going to build an anemometer (an instrument for measuring wind speed) with no moving parts, the teacher will be mystified, and will wonder whether it is even possible. But when they see the completed device in action, they will be astonished at its simplicity.

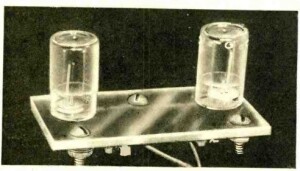

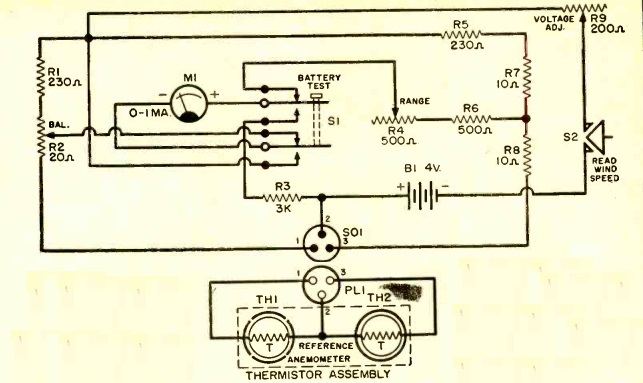

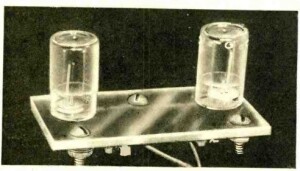

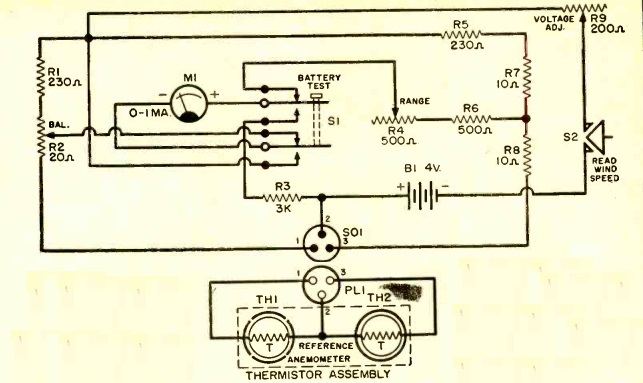

The anemometer consists of a Wheatstone bridge circuit, which consists of four resistors. Two of the resistors are actually thermistors of equal value. As long as their resistance remains equal, the meter shows a reading of zero. But if they are unequal, then the meter displays a current. The two thermistors are placed outside at the spot where the wind is to be measured. When they are energized, they heat up slightly, which causes their resistance to change. As shown at left, both are mounted in a small plastic container, but one of those containers has small holes drilled in it. When it is exposed to the wind, it is cooled, but the other thermistor is not. The stronger the wind, the greater the cooling, and the current increases. In other words, as the wind increases, it is shown on the meter.

The anemometer consists of a Wheatstone bridge circuit, which consists of four resistors. Two of the resistors are actually thermistors of equal value. As long as their resistance remains equal, the meter shows a reading of zero. But if they are unequal, then the meter displays a current. The two thermistors are placed outside at the spot where the wind is to be measured. When they are energized, they heat up slightly, which causes their resistance to change. As shown at left, both are mounted in a small plastic container, but one of those containers has small holes drilled in it. When it is exposed to the wind, it is cooled, but the other thermistor is not. The stronger the wind, the greater the cooling, and the current increases. In other words, as the wind increases, it is shown on the meter.

Once the meter is built, it needs to be calibrated, and that requires Junior to “enlist the services of a competent automobile driver” on a “highway which permits maximum state speed limits.” The driver accelerates to 60 MPH, and Junior holds the thermistor assembly out the window, as far as possible. (We note that Junior should take care not to have the arm amputated by a passing truck.) Junior then adjusts the instrument so that it indicates a full scale reading on the meter. The measurement is taken again at different speeds, and the meter reading is noted.

When Junior is awarded the blue ribbon for this elegantly simple design, the teacher will undoubtedly be thinking, “why didn’t I think of that?”

The original construction article, from the February 1957 issue of Popular Electronics, called for a “matched pair” of thermistors, since they need to have equal values. While it might not be possible to buy a matched pair, there is an inexpensive alternative. Junior can buy this set of 100 thermistors on Amazon at a very reasonable price. It includes 10 each of different values, including the needed 2kΩ. Junior just needs to measure all ten, and then use the two that are the closest in value. The remaining 98 thermistors can be used for other experiments. In fact, by adjusting the values of the other resistors, another value of thermistor could be used.

Some links on this site are affiliate links, meaning that this site earns a small commission if you make a purchase after clicking on the link.

Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you’ve noticed that inflation is once again a thing, and prices of just about everything are skyrocketing. But the kids shouldn’t suffer just because politicians can’t get their act together. And if the kids need a nice table, then you can provide them with one at zero cost.

Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you’ve noticed that inflation is once again a thing, and prices of just about everything are skyrocketing. But the kids shouldn’t suffer just because politicians can’t get their act together. And if the kids need a nice table, then you can provide them with one at zero cost.