This past weekend was ARRL Field Day, an operating event in which Amateur Radio operators set up in the field and see how many contacts they can make with portable equipment. It’s mostly a fun activity, but it also serves as a test of emergency capabilities. For many, this involves hauling large equipment, often powered by a gasoline generator, and setting up large antennas. Often, large groups are involved in these operations. It’s been around since 1933, so this year’s running marked the 90th anniversary.

This past weekend was ARRL Field Day, an operating event in which Amateur Radio operators set up in the field and see how many contacts they can make with portable equipment. It’s mostly a fun activity, but it also serves as a test of emergency capabilities. For many, this involves hauling large equipment, often powered by a gasoline generator, and setting up large antennas. Often, large groups are involved in these operations. It’s been around since 1933, so this year’s running marked the 90th anniversary.

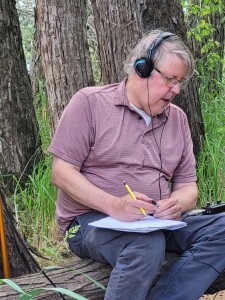

I prefer a simpler approach, and set out by myself or a smaller group with equipment that I can easily carry and quickly set up. This year, instead of just driving to a park, I decided to operate from an island accessible only by boat. In particular, I operated from Greenberg Island in the St. Croix River, part of William O’Brien State Park, Minnesota. The plan was for my wife and I to do the operation, bringing our canoe from home.

I prefer a simpler approach, and set out by myself or a smaller group with equipment that I can easily carry and quickly set up. This year, instead of just driving to a park, I decided to operate from an island accessible only by boat. In particular, I operated from Greenberg Island in the St. Croix River, part of William O’Brien State Park, Minnesota. The plan was for my wife and I to do the operation, bringing our canoe from home.

Setting up one end of my antenna. I’m breaking of a stick which I used as a stake to anchor it in the sand.

The initial weather reports didn’t look promising, so we decided not to take the canoe, and instead just operate from the mainland. But while driving there, the weather looked fine, so we decided to rent a canoe and activate the island as originally planned.

The island has been part of the park since 1958. When I was a kid, there was a pedestrian bridge linking it to the mainland, with a trail covering part of the island. Exploring the island was always a fun part of a trip to the park. The bridge is long gone, and the only way to access it is by boat. I did check first, and it’s perfectly legal to land there, although it is posted “No Camping.” And not having been there for about 50 years, it was fun to explore the island again, but there was no trace of the old trails.

There were a few human footprints on the beach, but not many. At the beach where we landed, there were deer footprints, as well as either a dog or a wolf. The only other sign of humans was a fairly recent mylar balloon reading “happy birthday” which had landed in the brush just off the beach. I inspected it carefully to see if it carried a note. Unfortunately it didn’t, so I just picked it up and took it to a trash can on the mainland.

I was on the air from about 3:30 – 5:00 PM, and the weather held up fine. It started looking like rain and we headed back. We had a few drops of rain, but it didn’t start pouring until we had just left the park on the way home.

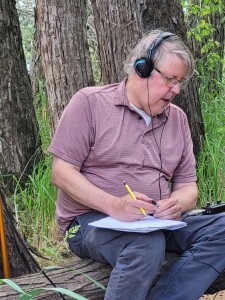

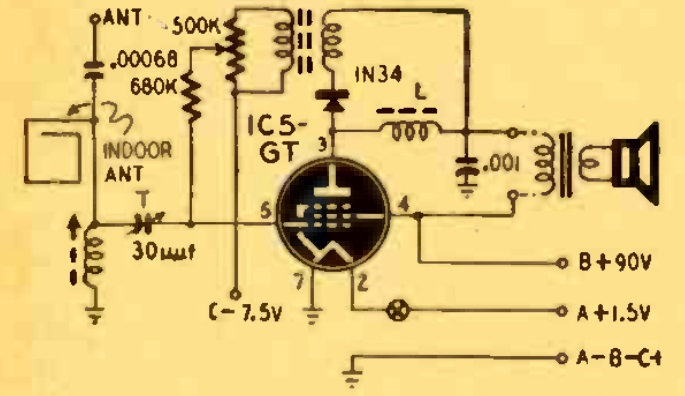

We found a beach on the east side of the island, and set up there. I used the QCX Mini, running 5 watts on 40 meter CW, and worked about 20 contacts. The antenna was an inverted vee supported my trusty golf ball retriever shoved into the sand and leaning against a tree. The power source was a fish finder battery. I did purchase it new for Field Day, since the previous one was showing signs of wear after 7 years of abuse.

I forgot to bring a folding chair (although my wife remembered hers and was able to relax while I operated). The fallen tree shown above served as a suitable substitute.

Heading home. KC0OIA at the bow, W0IS at the stern.

Best DX was Alabama, I believe. In addition to working Field Day, I submitted the logs for Parks On The Air (POTA), WWFF-KFF, and U.S. Islands Awards Program. This is the first time the island has been activated, and since we went over the magic number of 15 QSOs, it will count as being “qualified” for that program.

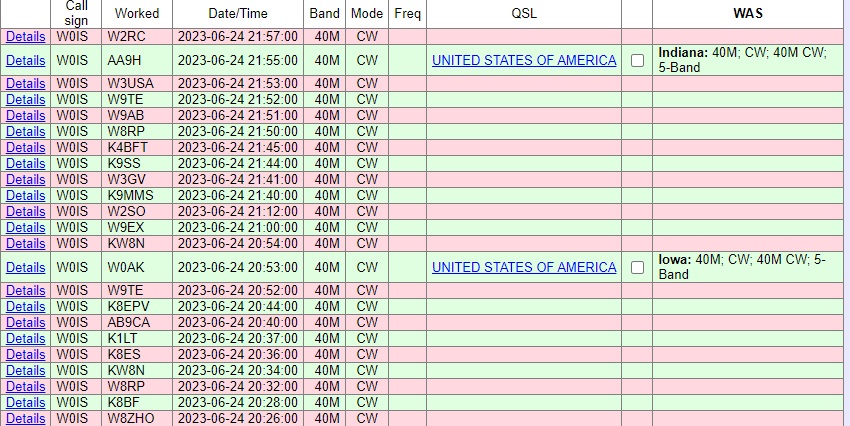

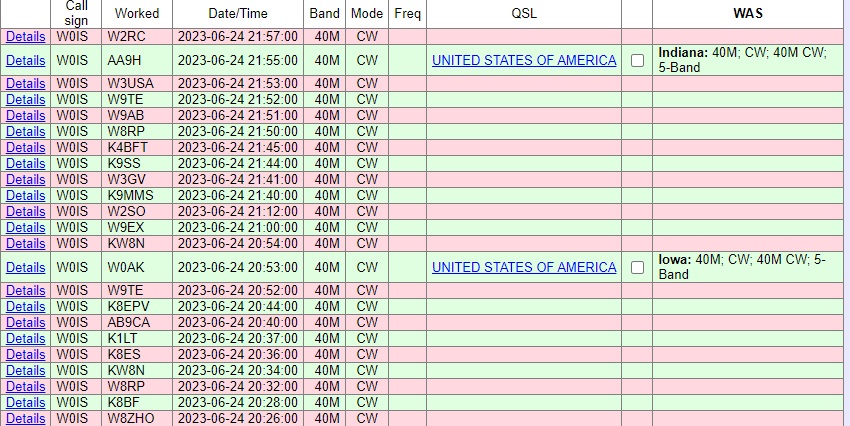

Thanks to the stations shown below, some at home, and some out in the field, for pulling in my 5 watt signal. If you look carefully, you’ll see three dupes. All of my logging is pencil and notebook, so sometimes it’s hard to remember who I just worked.

Will I ever save the world with my communications abilities? Probably not. But it’s good to know that with equipment I can carry with me, just a few minutes setting up, and a battery found in any car, I could get messages out to my friends and relatives in case of disaster, and could do the same thing for my neighbors.

Some links are affiliate links, meaning that this site earns a small commission if you make a purchase after using the link.

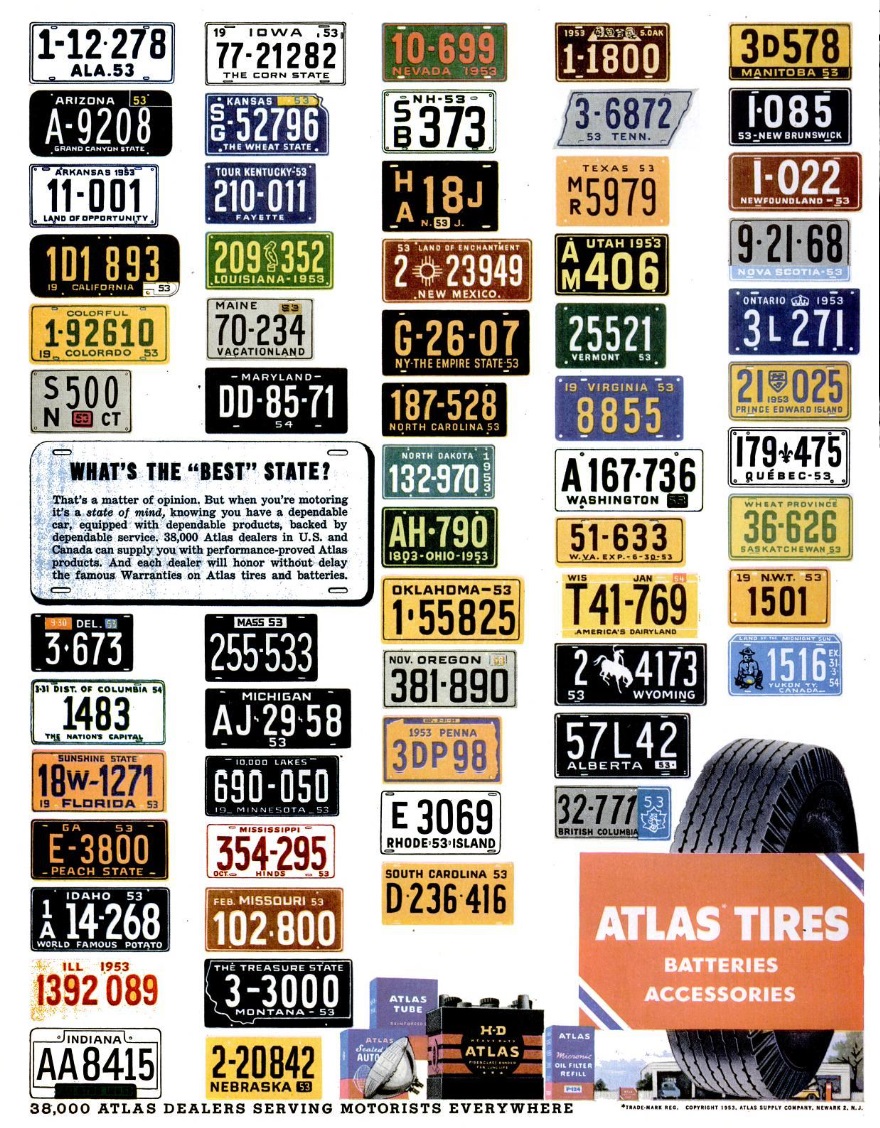

If you’re wondering what your state or province’s license plate looked like 70 years ago, here’s a complete collection. This ad for Atlas Tires appeared 70 years ago today in the June 29, 1953, issue of Life Magazine.

If you’re wondering what your state or province’s license plate looked like 70 years ago, here’s a complete collection. This ad for Atlas Tires appeared 70 years ago today in the June 29, 1953, issue of Life Magazine.