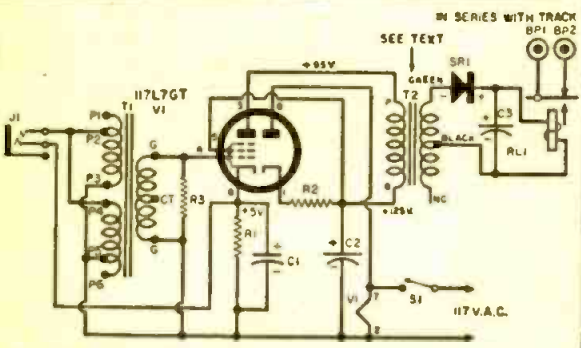

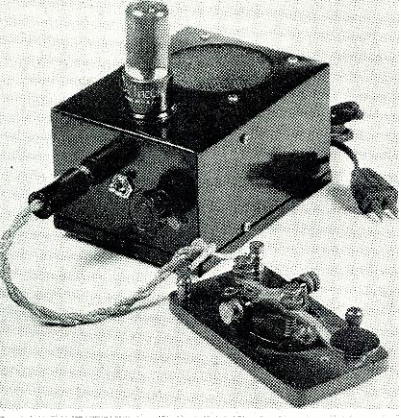

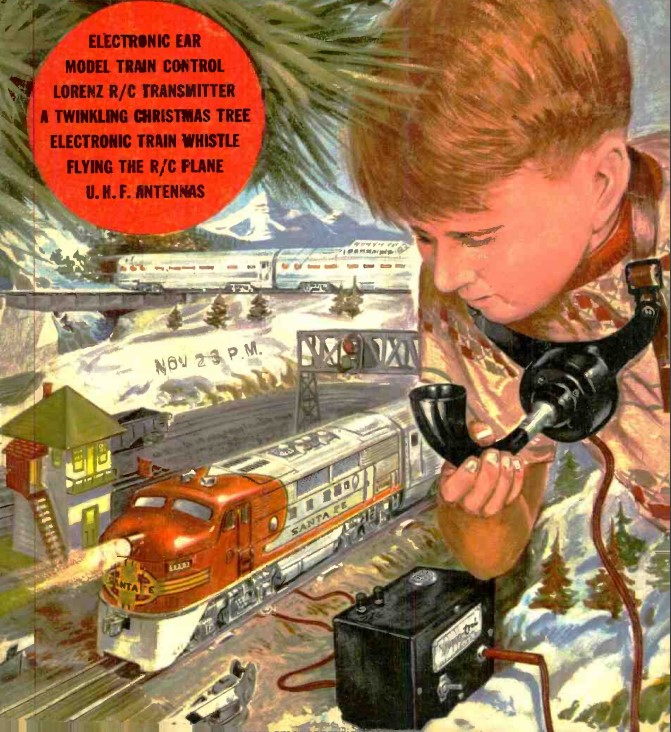

Seventy years ago, this young man was deriving new enjoyment from his train set, thanks to the voice control system his dad put together, from the plans in the December 1953 issue of Popular Electronics.

Seventy years ago, this young man was deriving new enjoyment from his train set, thanks to the voice control system his dad put together, from the plans in the December 1953 issue of Popular Electronics.

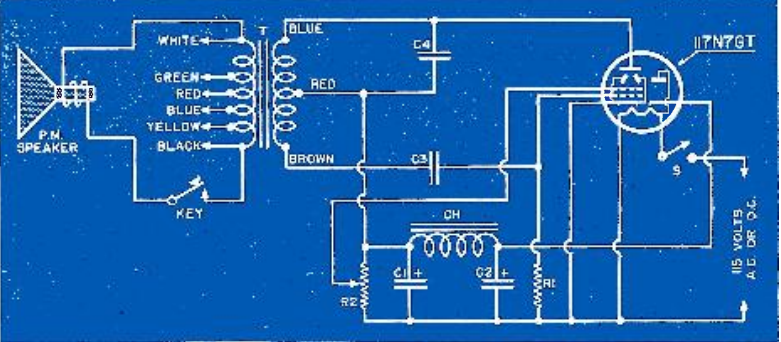

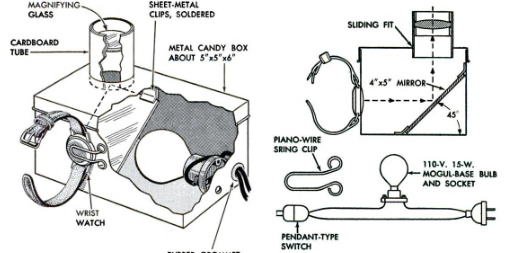

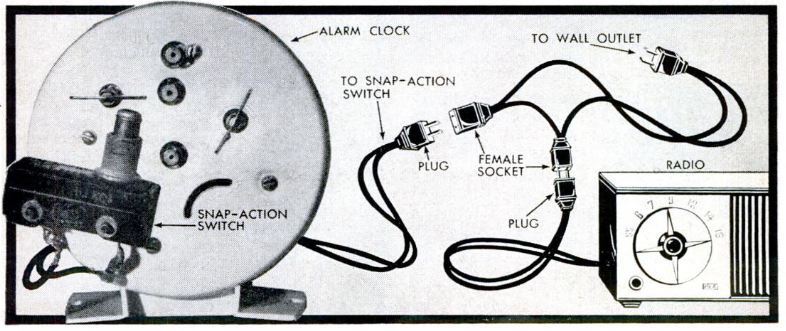

The system would cycle through forward, stop, and reverse commands. The actual words used didn’t matter, but with a bit of creativity, Junior could make it look like the device understood exactly what he said. For example, if the train was moving forward, then barking “stop” would have the desired effect. From a stop, the word “reverse” would do the trick. If the train was going backwards, then “now go forward” would give three syllables, making it cycle through to the forward mode.

The device was compatible with both Lionel and American Flyer train sets.